Why this site

Why this site

Ottavio Sbragia (June 2021)

Questo sito Ŕ un tardivo omaggio all'opera di Esmeralda Ruspoli, mia madre.

L'idea Ŕ maturata negli ultimi anni quando ho iniziato a guardare

le opere che conservo nel mio appartamento attraverso gli occhi dei numerosi ospiti di mia moglie, totalmente estranei al mondo di mia madre, persone

di etÓ e professioni differenti, provenienti dai cinque continenti, che ne rimanevano sorpresi e affascinati. Le osservazioni, la sincera curiositÓ

e ammirazione di queste persone hanno rivoluzionato il mio sguardo nei confronti del suo lavoro.

Ho sempre guardato, infatti, quei collages non

come opere d'arte ma come l'espressione di un aspetto della sua personalitÓ: un mondo misterioso un po' folle e allo stesso tempo imperscrutabile tradotto

in oggetti; certo decorativi ma anche spesso inquietanti o provocatori.

Questo sguardo "intimo" alla sua opera Ŕ probabilmente stato suggerito

dallo stesso atteggiamento che lei aveva in famiglia. Malgrado il Collage sia stato il fil rouge della sua vita non Ŕ mai stato presentato a noi figli

come una professione che trovava conferma in un corrispettivo valore economico vista anche la totale assenza in lei di una capacitÓ manageriale e mercantile.

Devo ricordare, inoltre, negli anni della mia infanzia che quanto percepivo del filone dominante nel mondo dell'arte figurativa risultava costituito

dall'astrattismo al di fuori del quale non vi era espressione artistica possibile e credibile.

Tutto ci˛, sommato alla nostra abitudine di vedere

nascere continuamente dalle sue forbici incredibili collages, ha fatto sý che siano sempre state guardati, apprezzati ed amati pi¨ come my mother's stuff

che come opere d'arte.

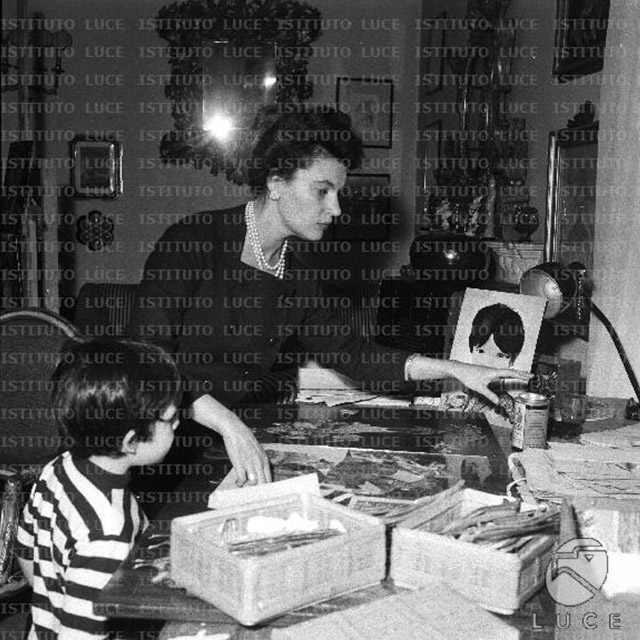

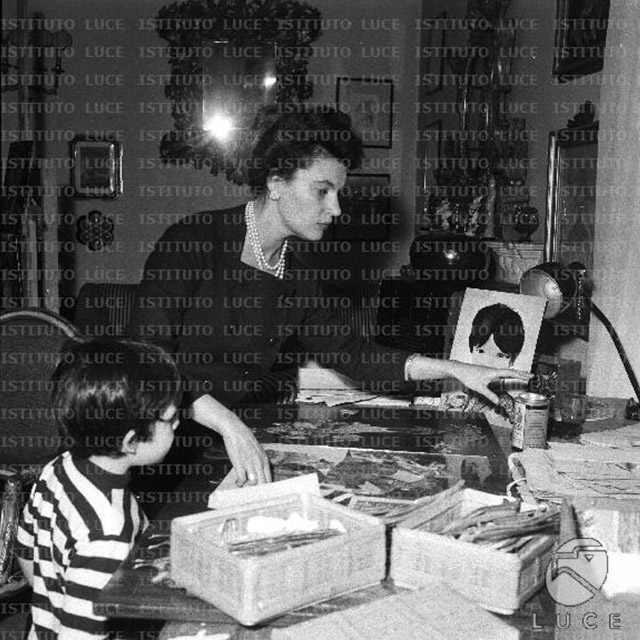

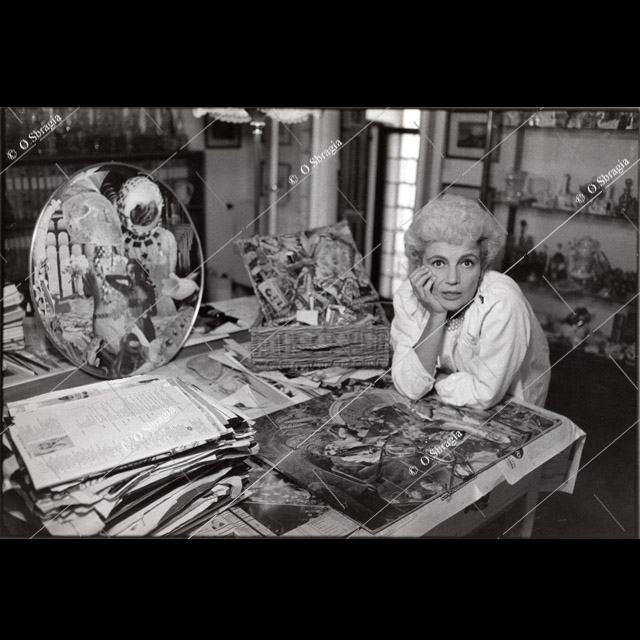

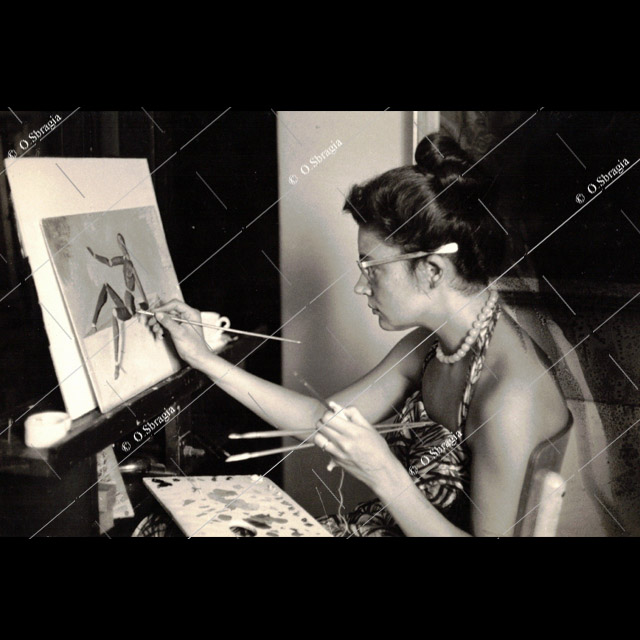

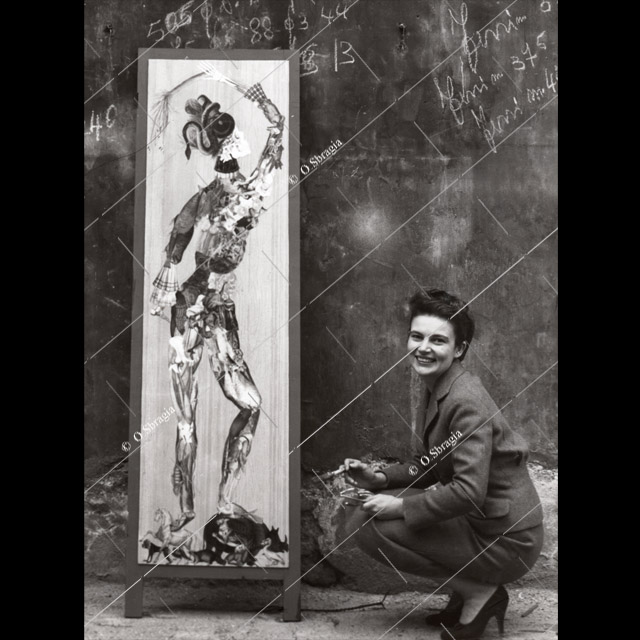

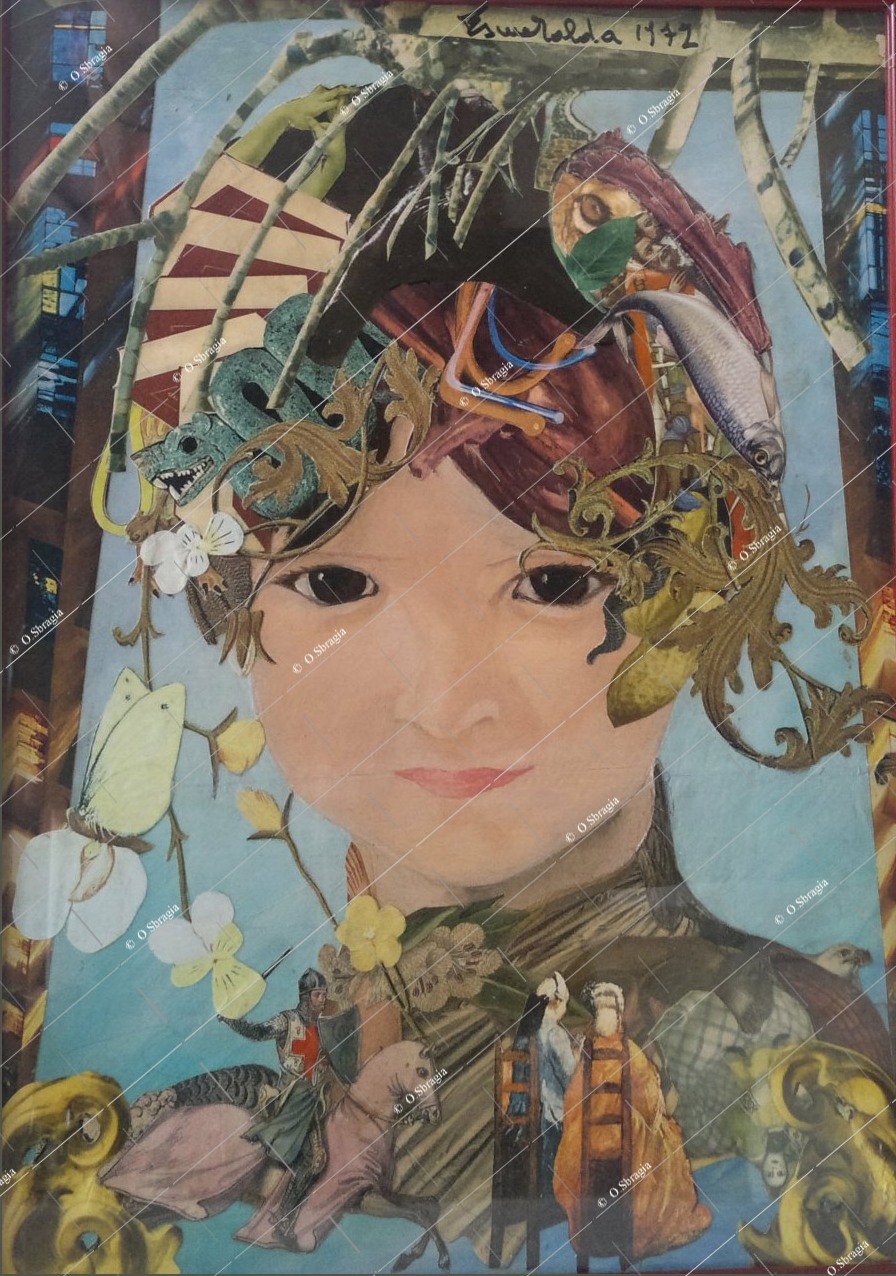

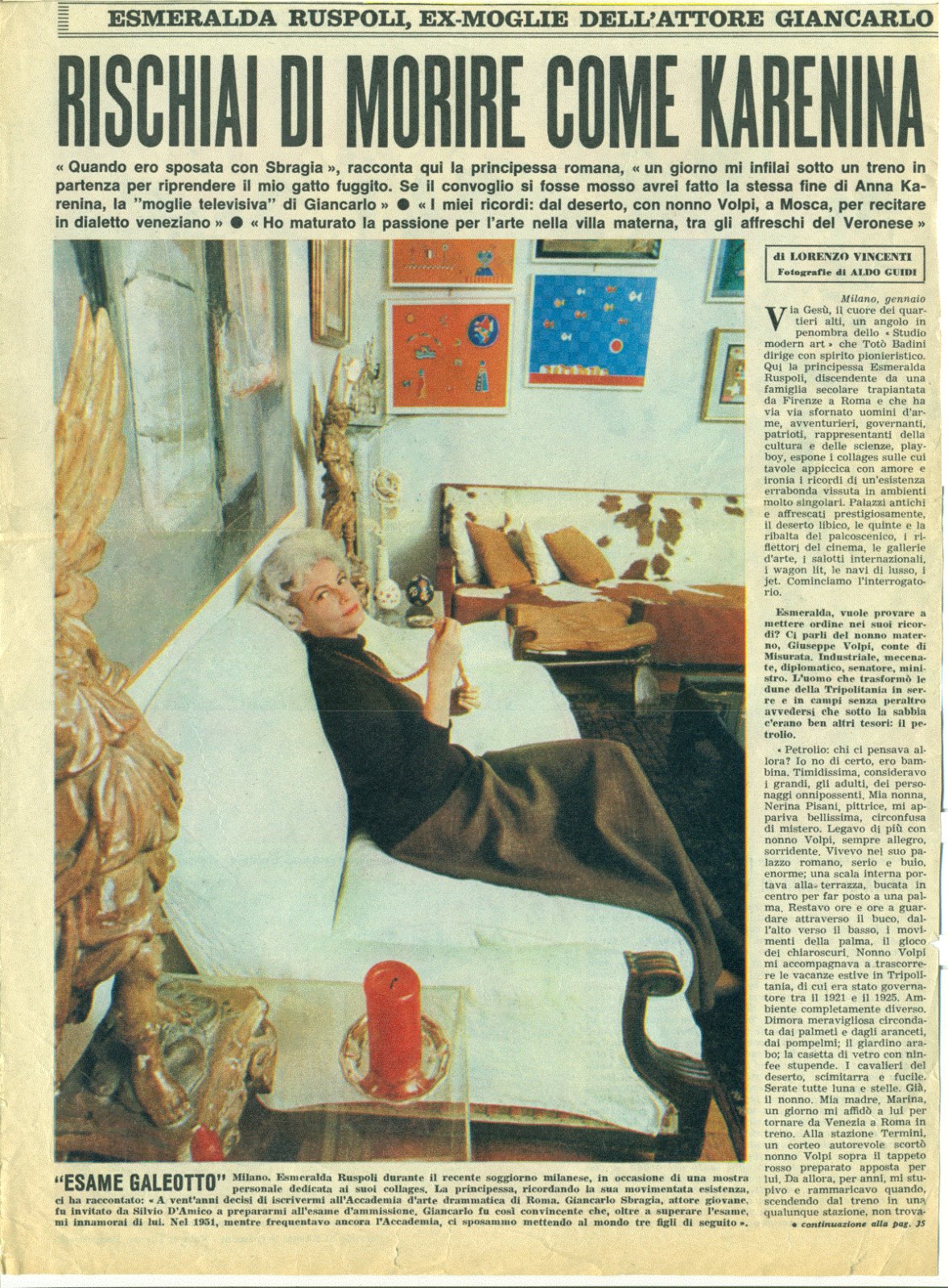

1958, Rome, with my brother

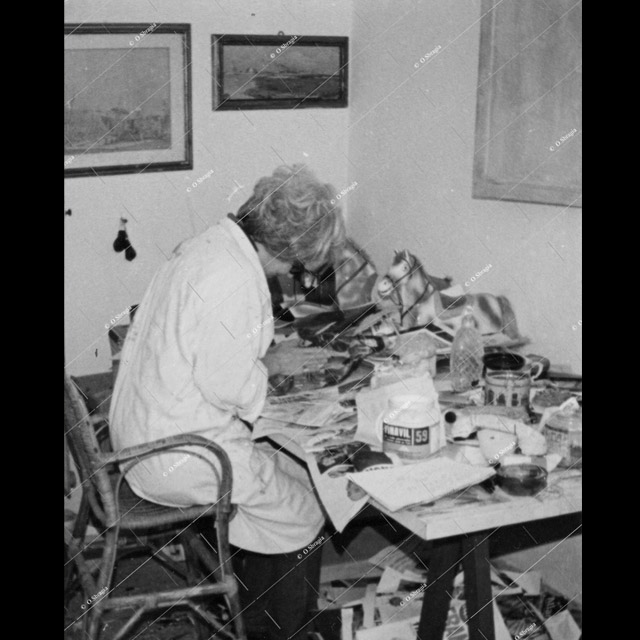

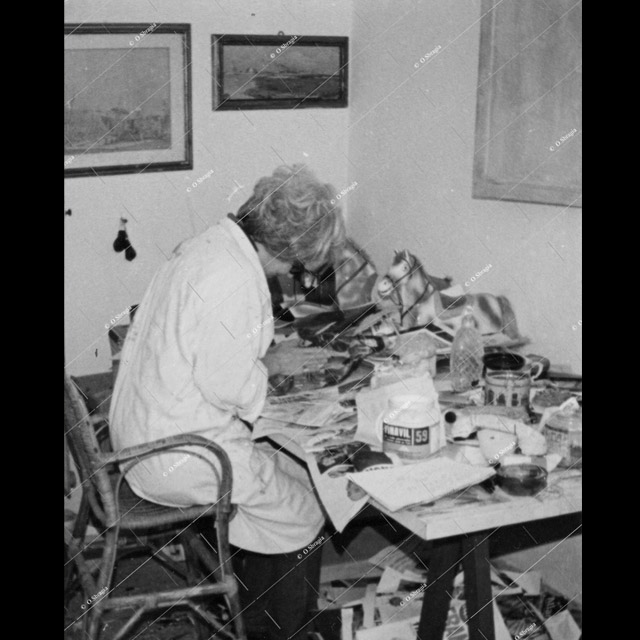

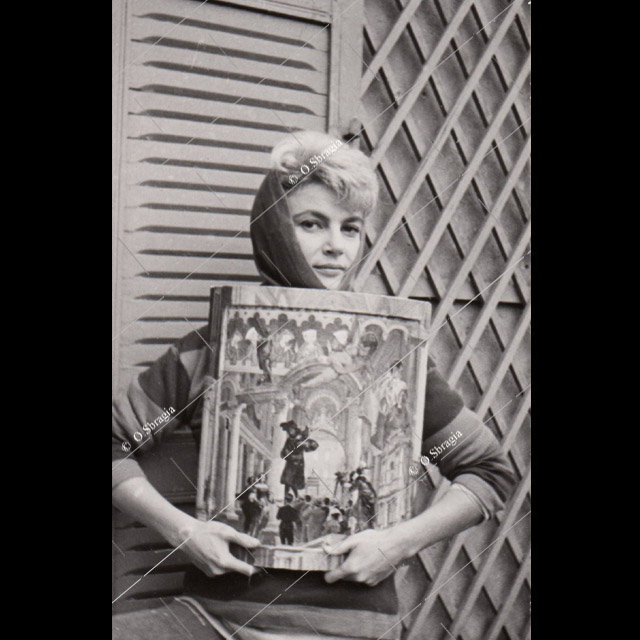

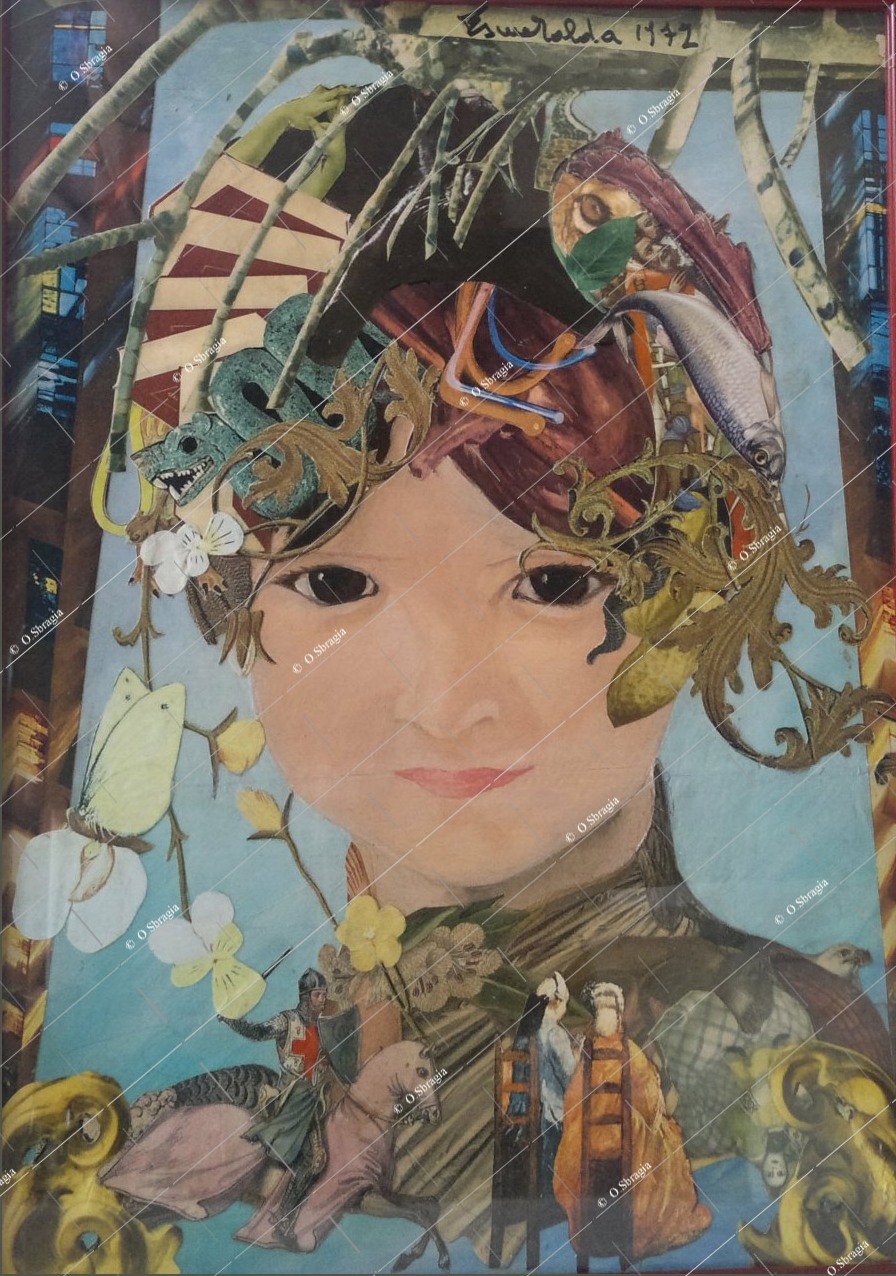

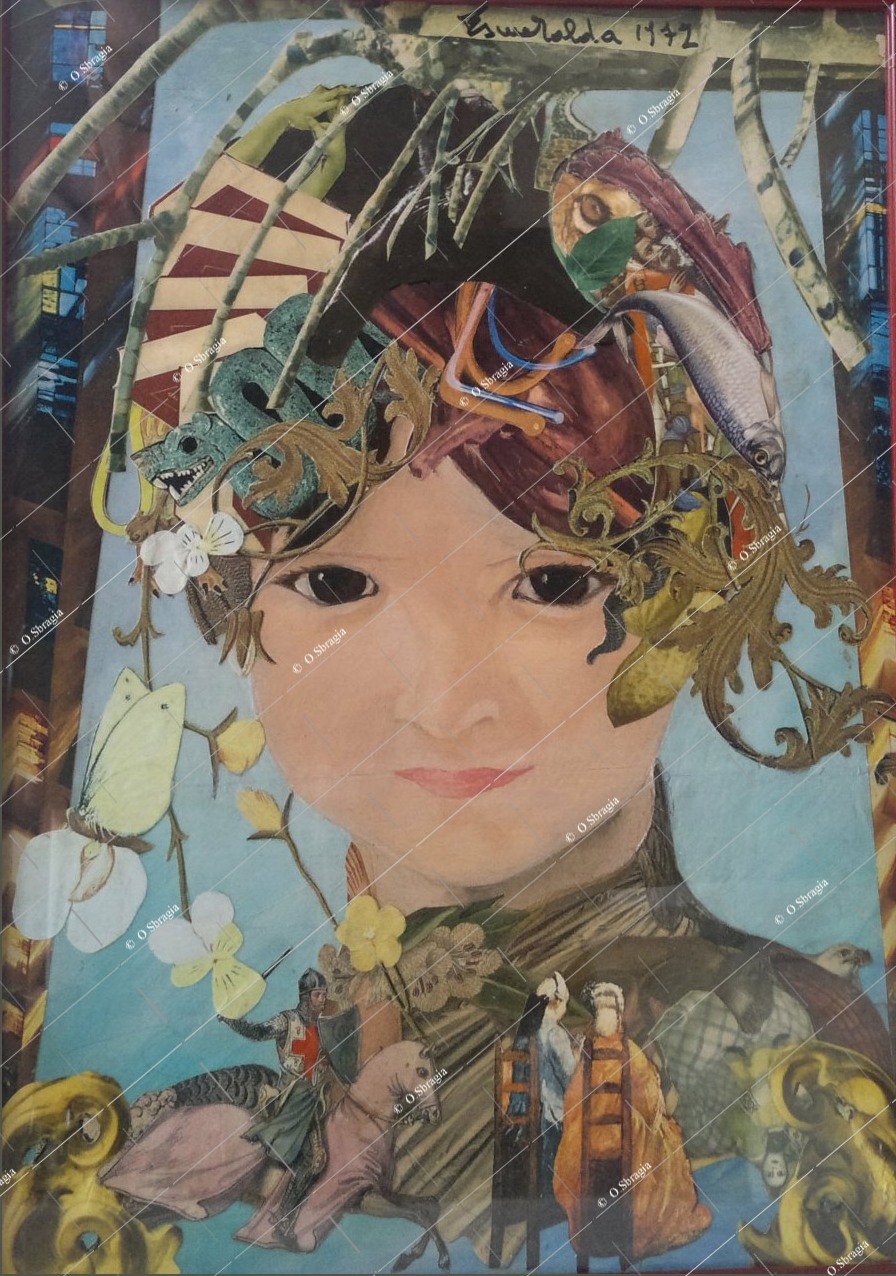

1972, Rome

L'immagine che conservo di lei al lavoro Ŕ immutabile nel corso della sua vita: seduta su un vecchio seggiolone di vimini

per bambini (sempre lo stesso, uno dei nostri) in modo di essere ad una altezza adatta allo scopo, china sul collage in lavorazione con l'immancabile paio di

forbici fra le dita (sempre le stesse che le erano state regalate dall'ostetrica che l'aveva assistita in uno dei suoi parti), intorno una gran confusione di

riviste, libri d'arte, stampe alcune ritagliate altre integre in mezzo alla quale pescava con preciso intuito la pagina contenente l'immagine desiderata.

Nell'aria un piacevole profumo di colla, il bianco Vinavil, che a me piaceva tantissimo.

Mia madre, maneggiava le forbici con perizia e velocitÓ chiacchierando

piacevolmente con chi la andava a trovare come facevano le donne della generazione precedente mentre lavoravano a maglia. A questa ambientazione intima riconducono

nei miei ricordi di bambino e poi di giovane uomo il processo creativo di my mother's stuff.

A trenta anni dalla morte ho iniziato, grazie ai miei ospiti,

a guardare i lavori di mia madre come "opere" che penso oggi trovino, in un mondo dell'arte pi¨ variegato, una loro collocazione storico artistica.

Auguro dunque al visitatore di questo sito di gioire il suo viaggio nel mondo straordinario di Esmeralda.

Ottavio Sbragia (June 2021)

This website is a belated homage to the work of Esmeralda Ruspoli, my mother.

The idea developed in recent years when I started to look at the works that I own in my apartment through the eyes of the many guests of my wife,

people who were totally extraneous to my mother's world, of different ages and professions, coming from five continents, people who were surprised

and fascinated. Their observations, sincere curiosity and admiration have revolutionised the way I have been looking at her work.

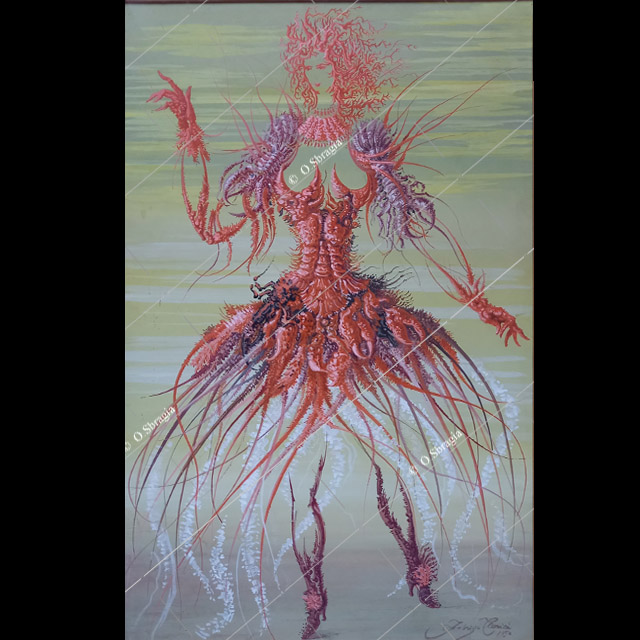

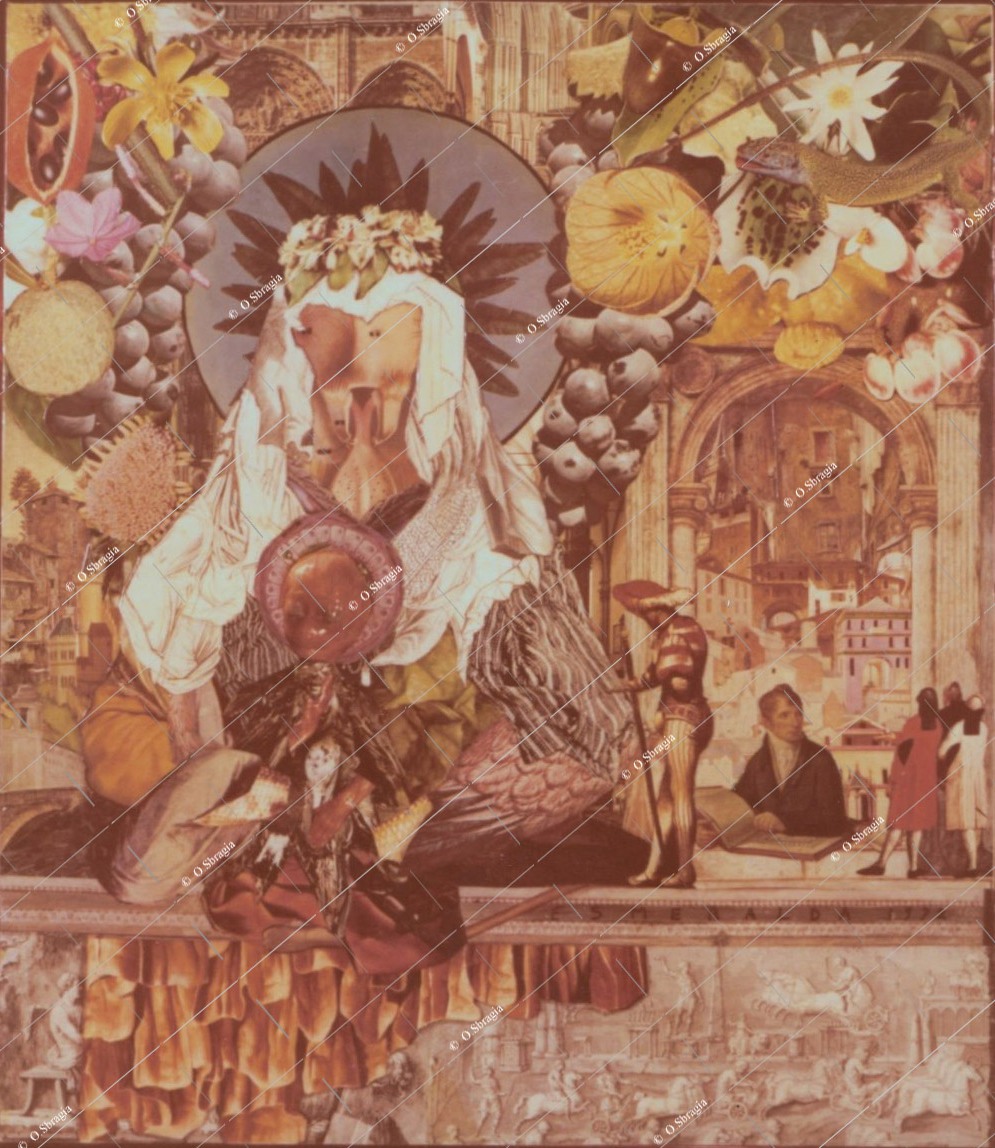

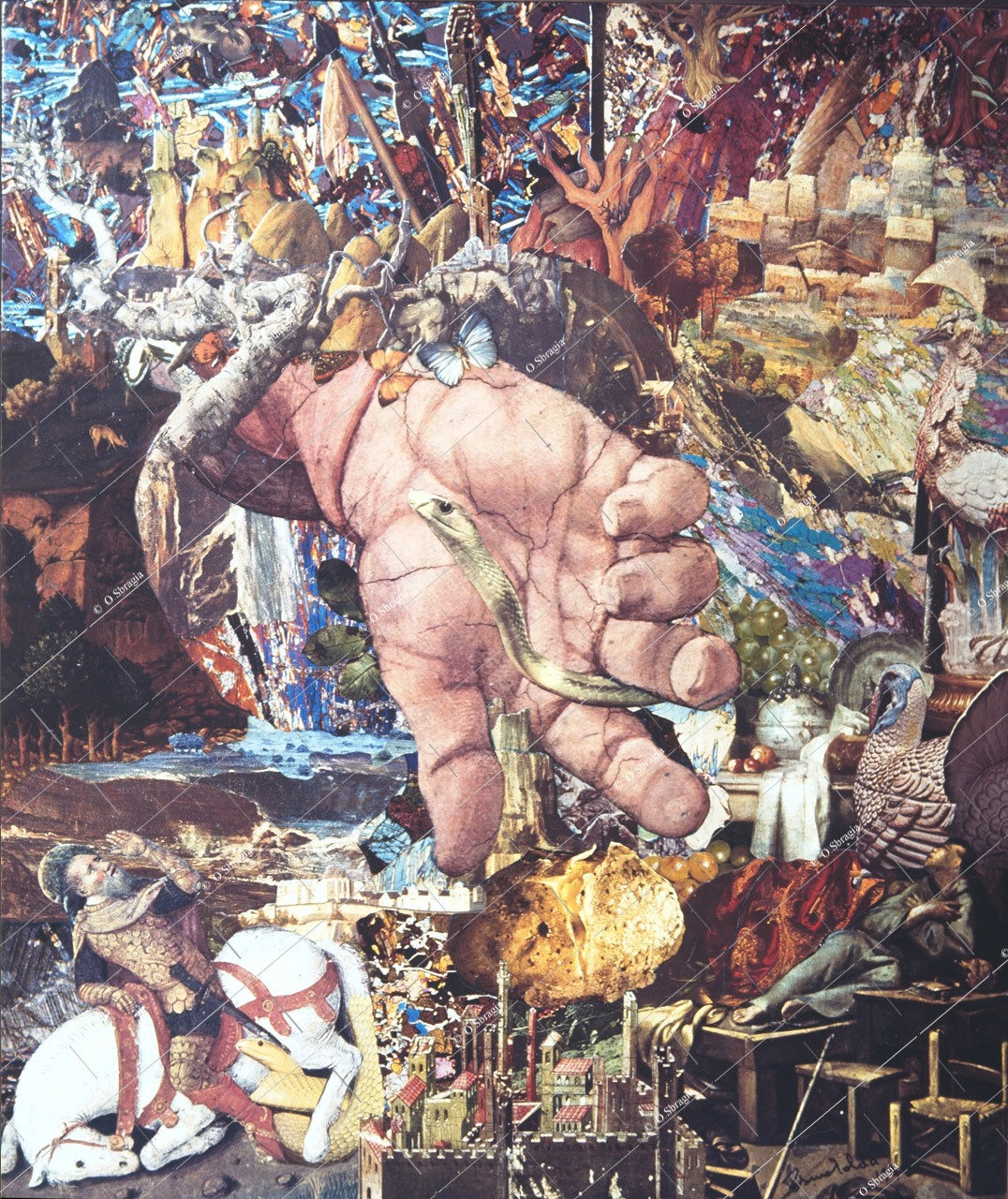

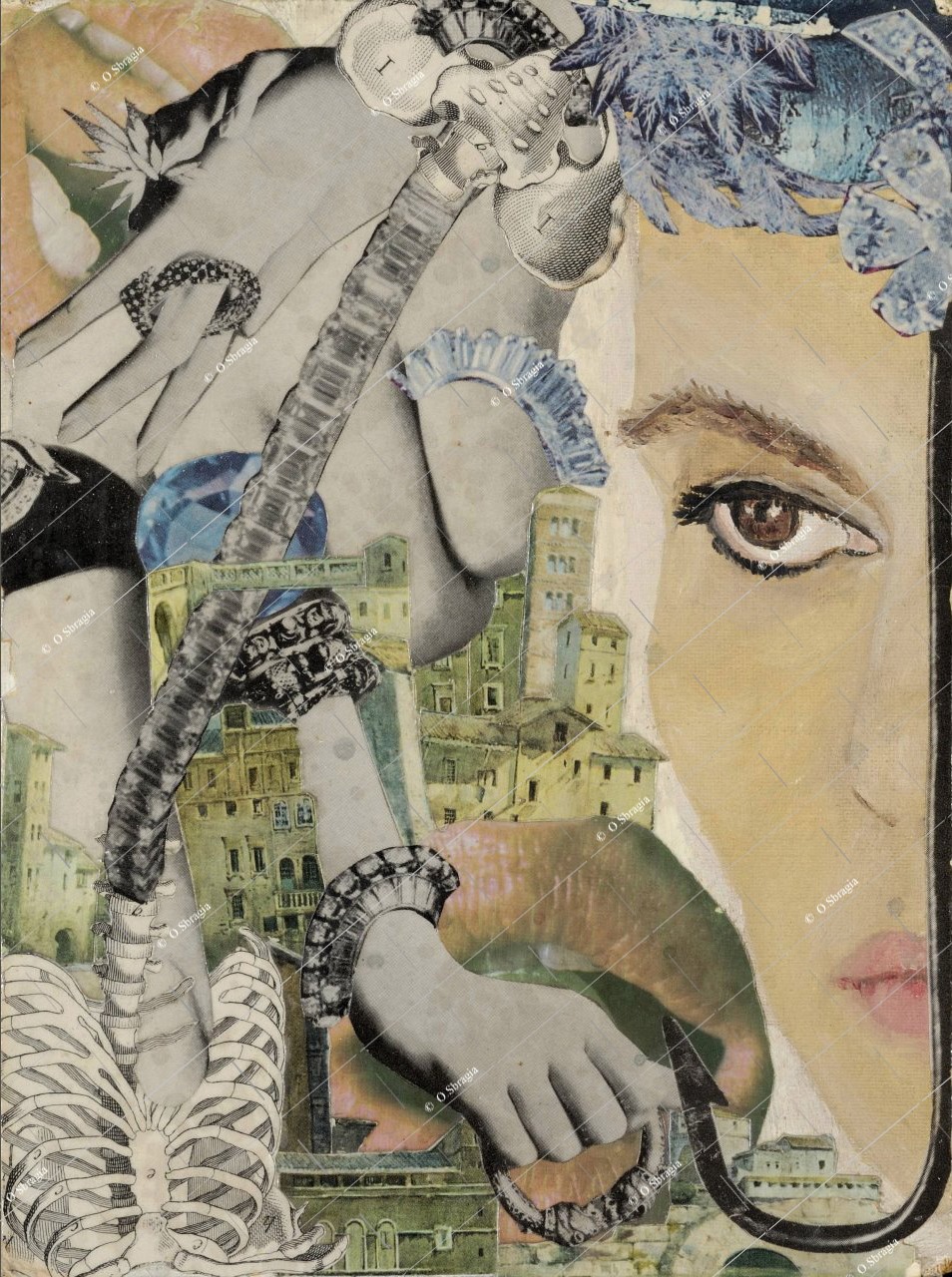

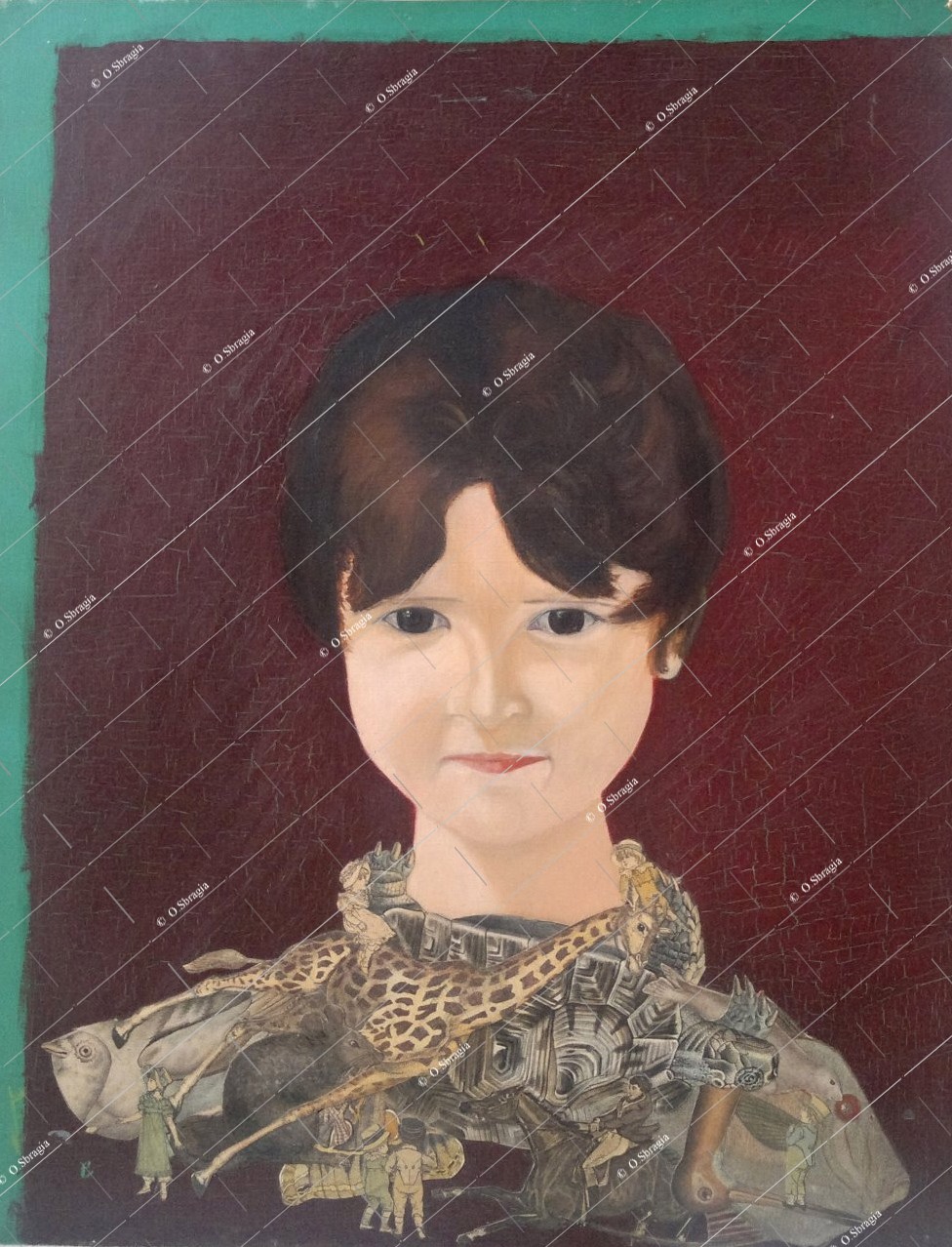

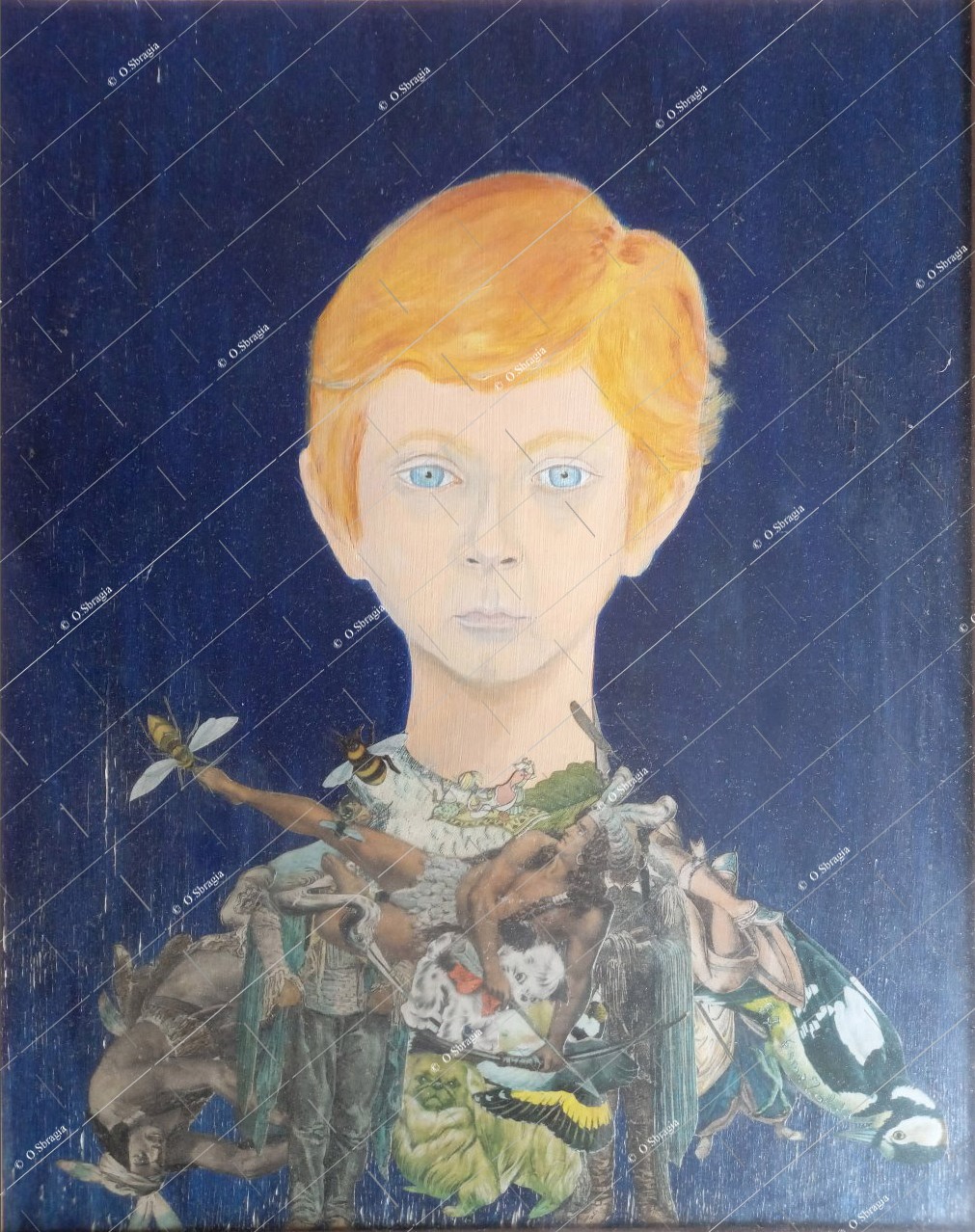

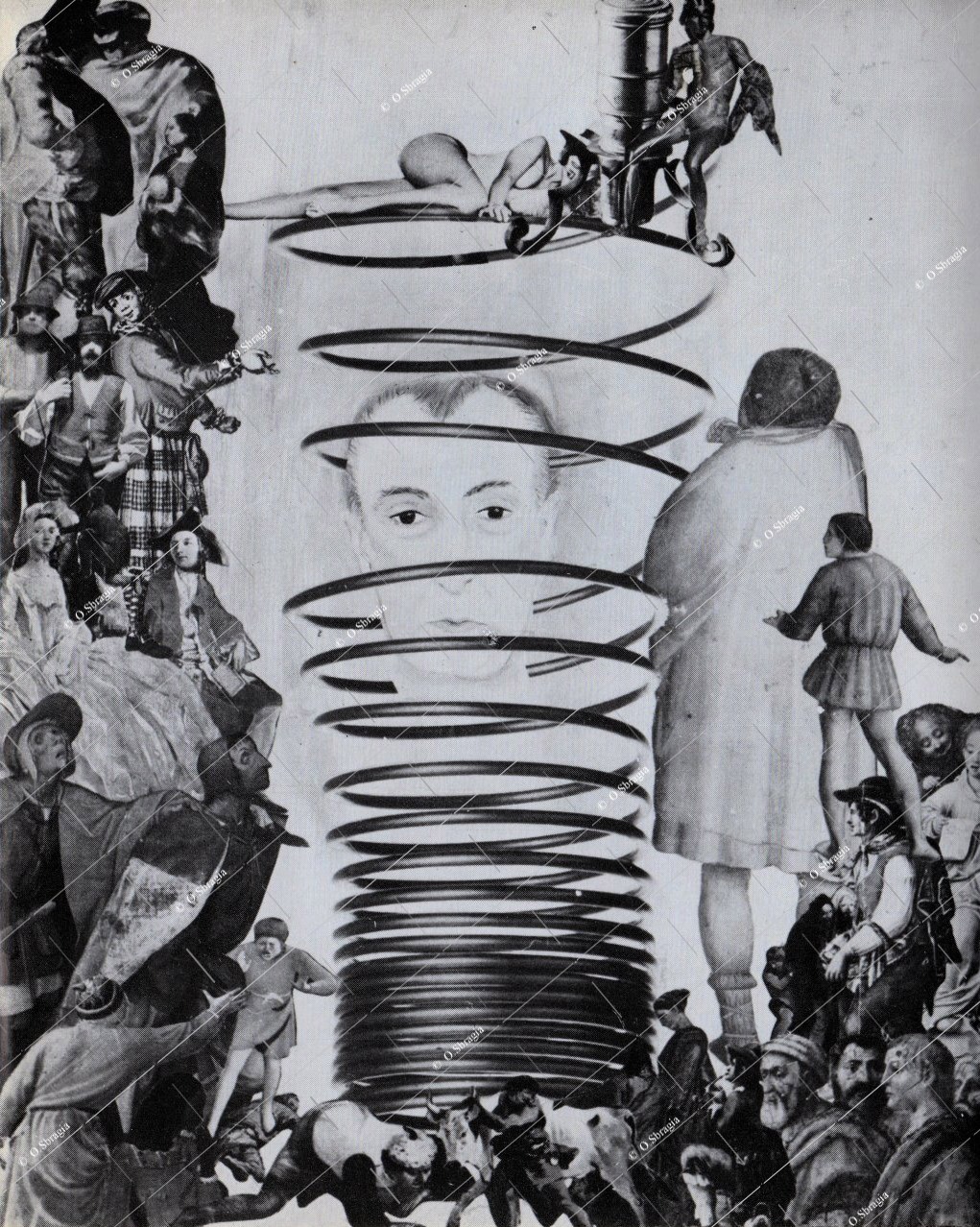

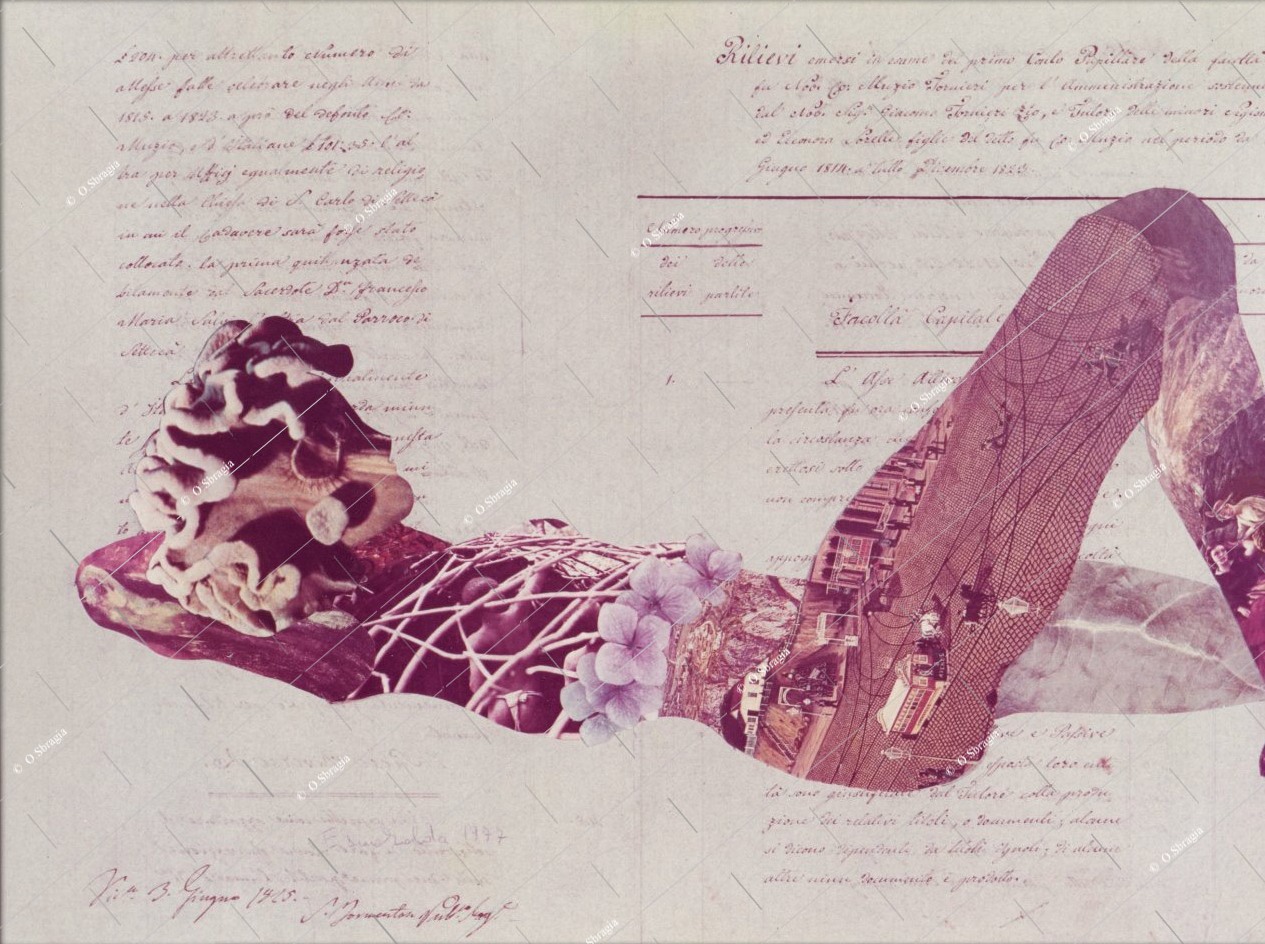

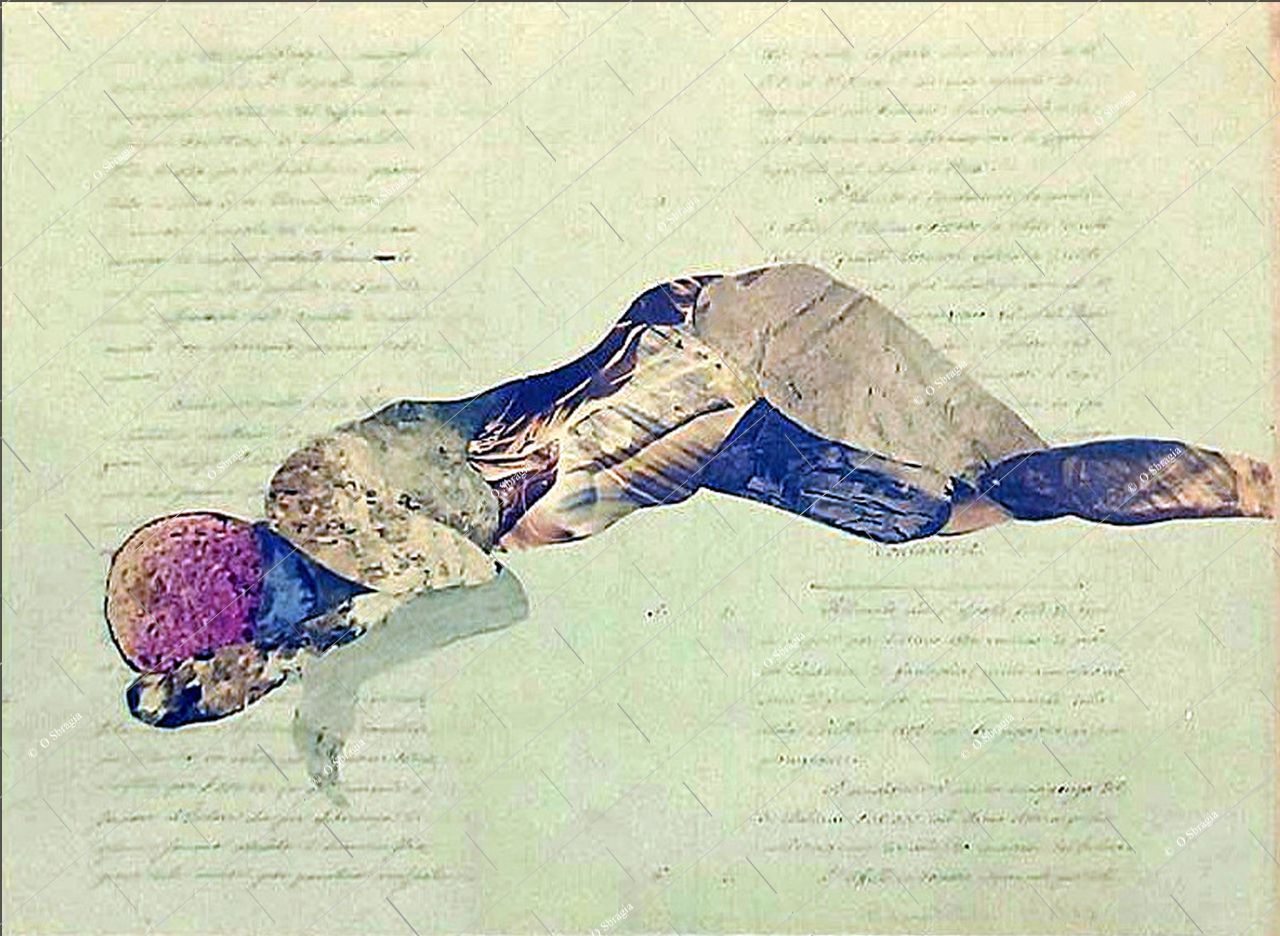

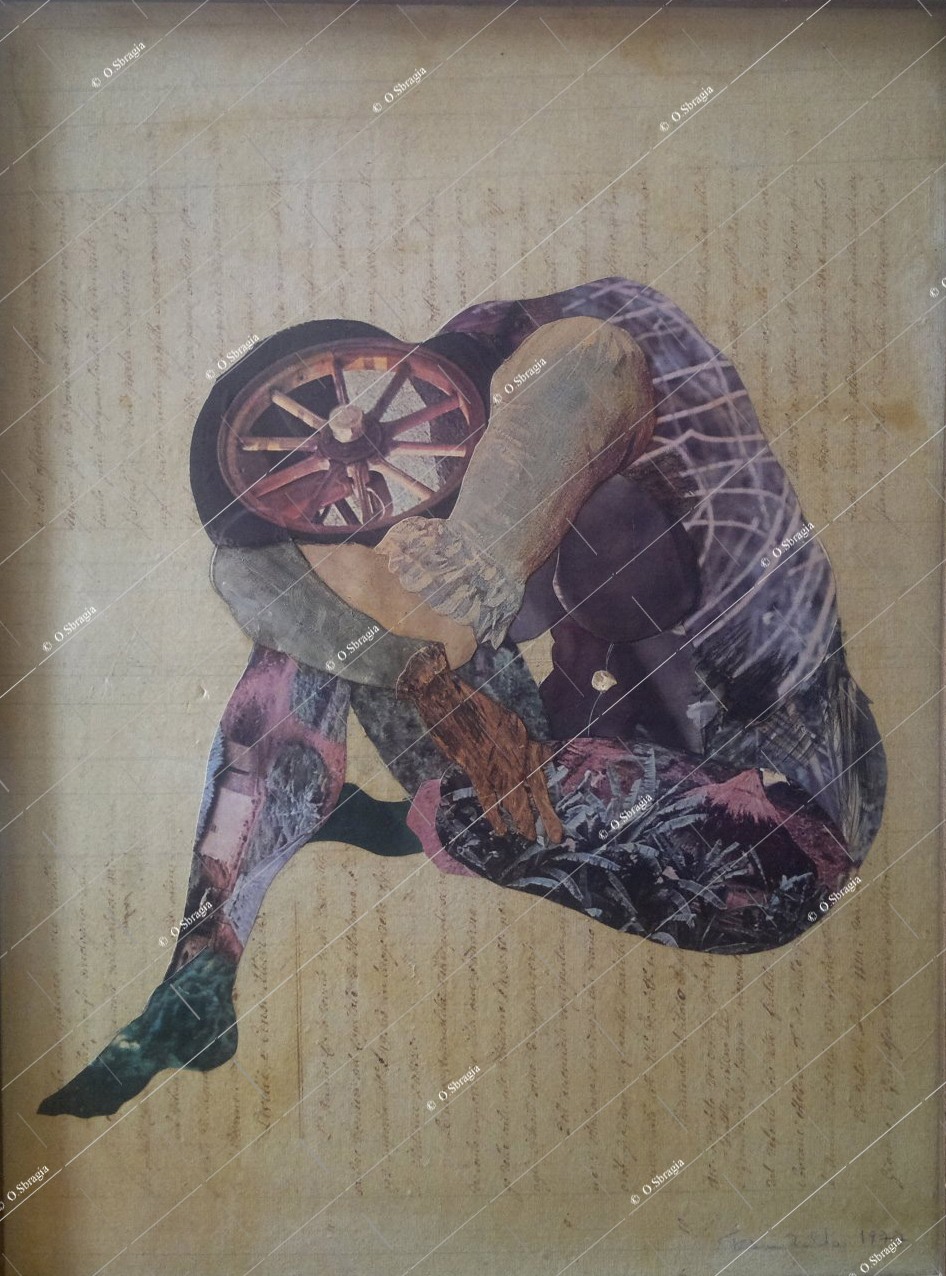

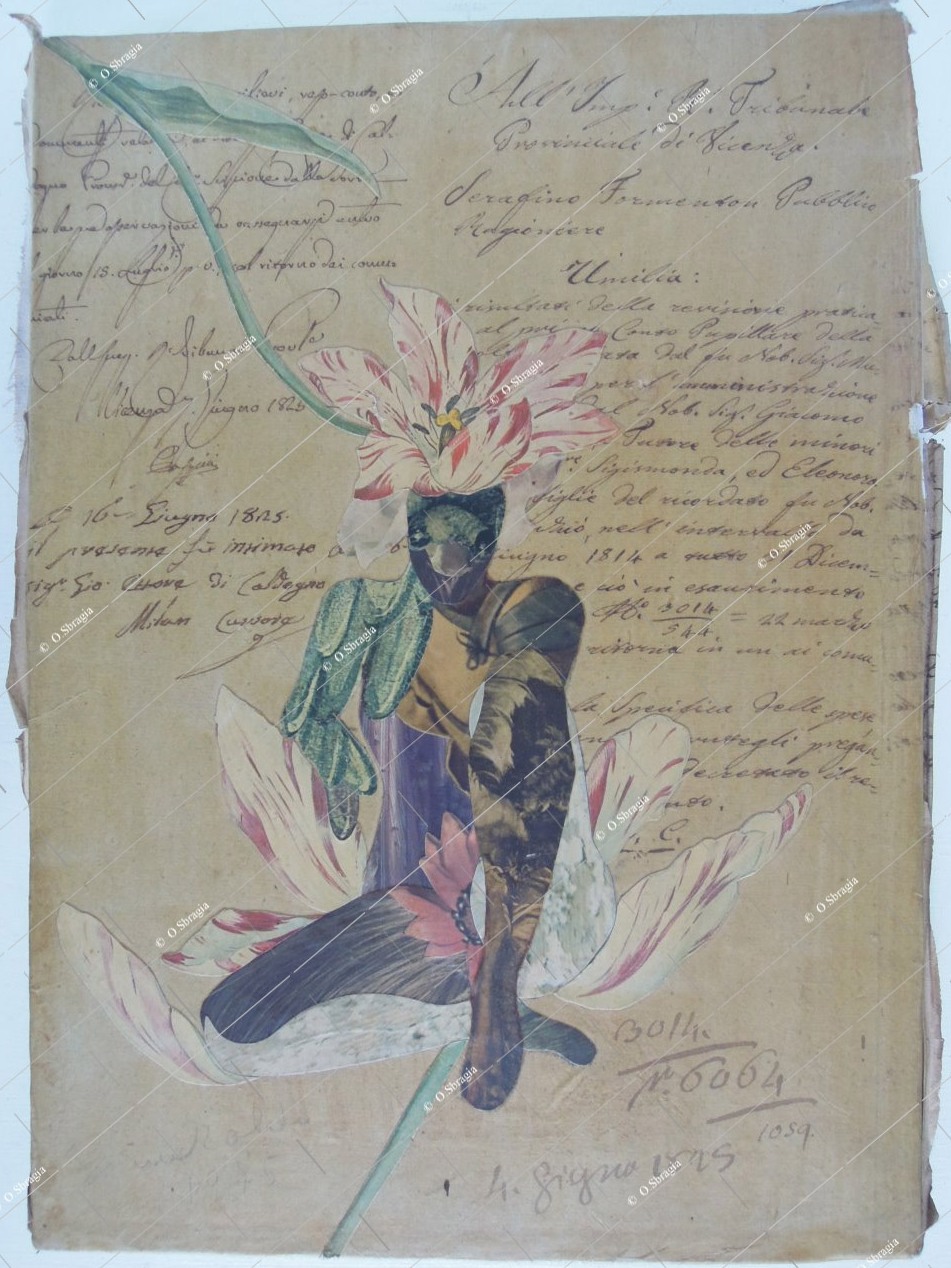

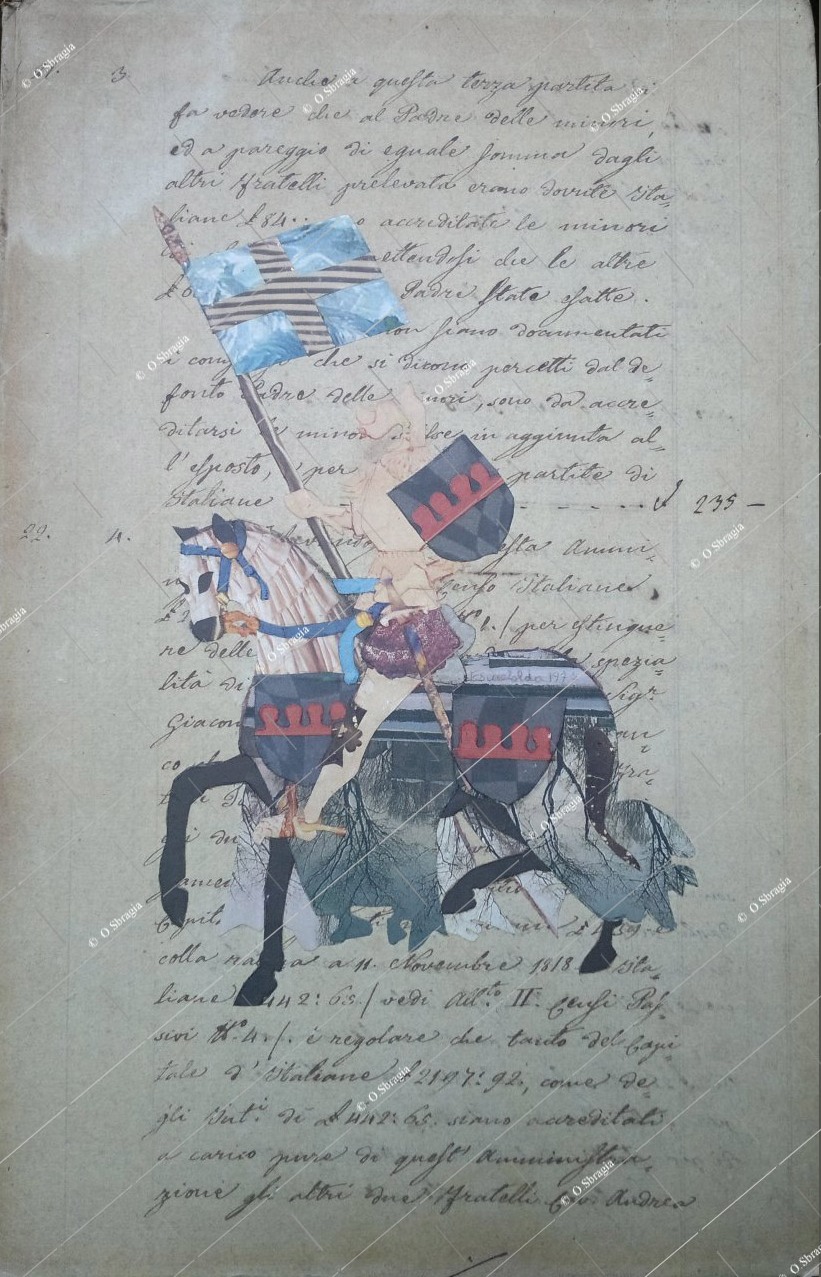

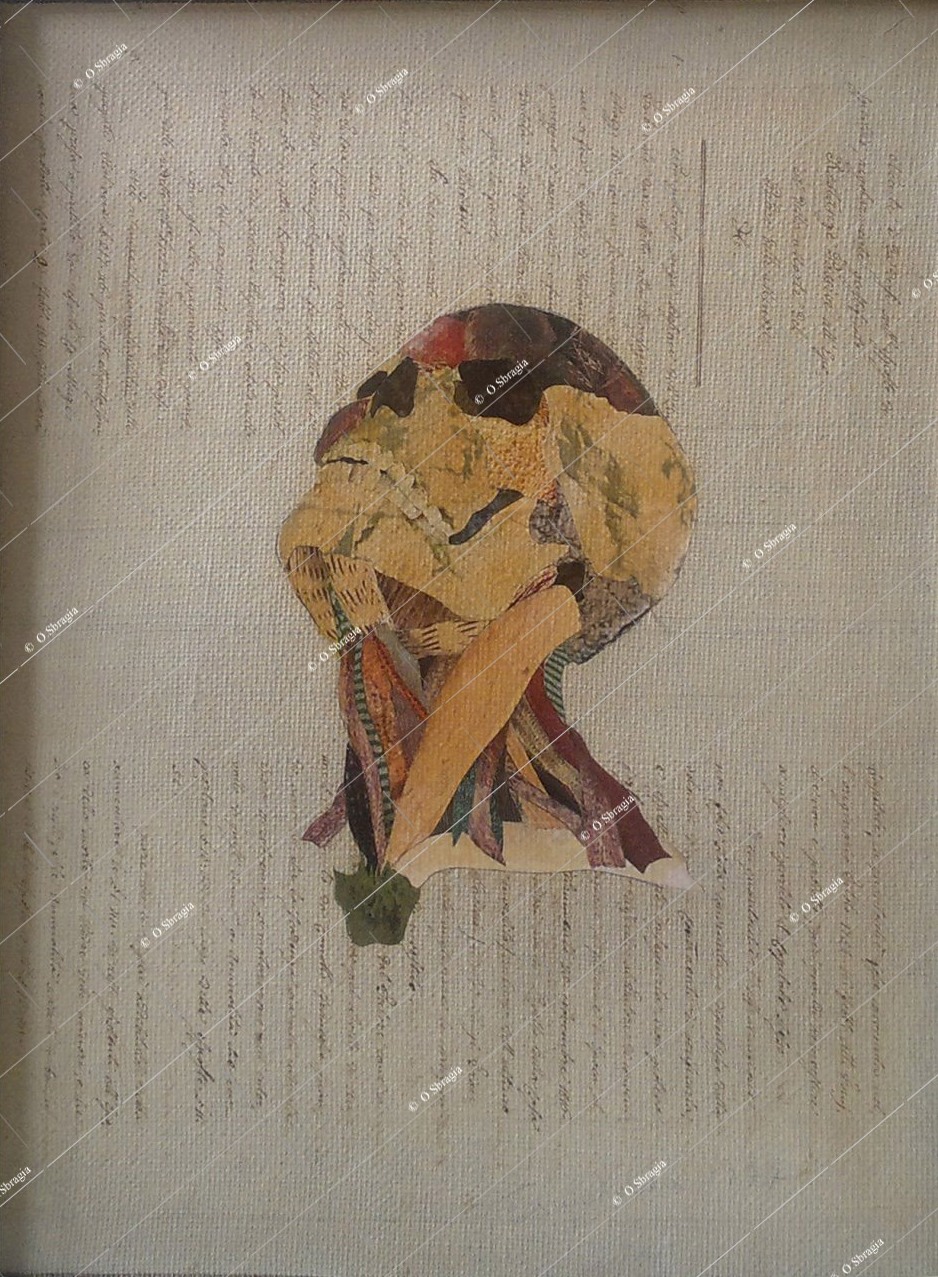

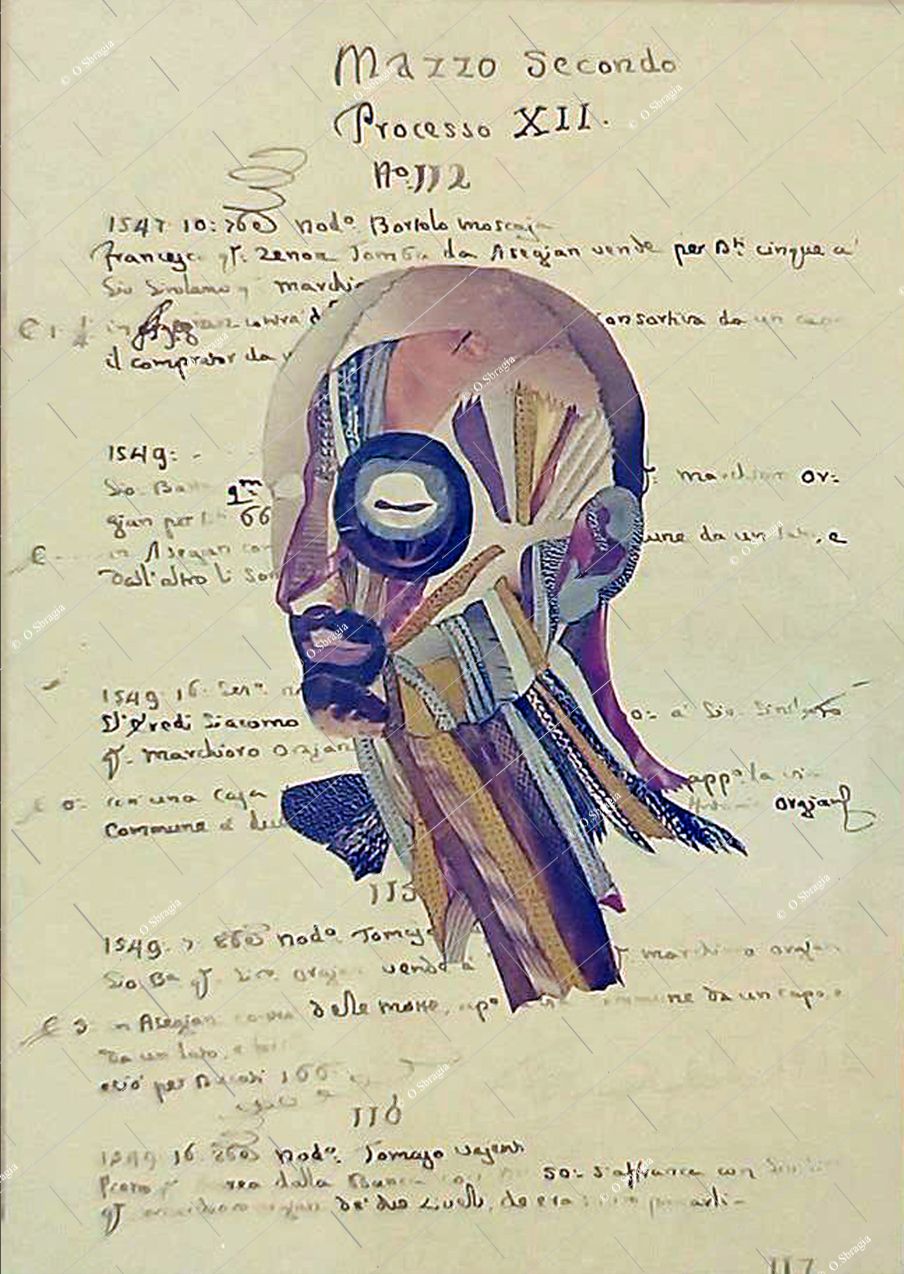

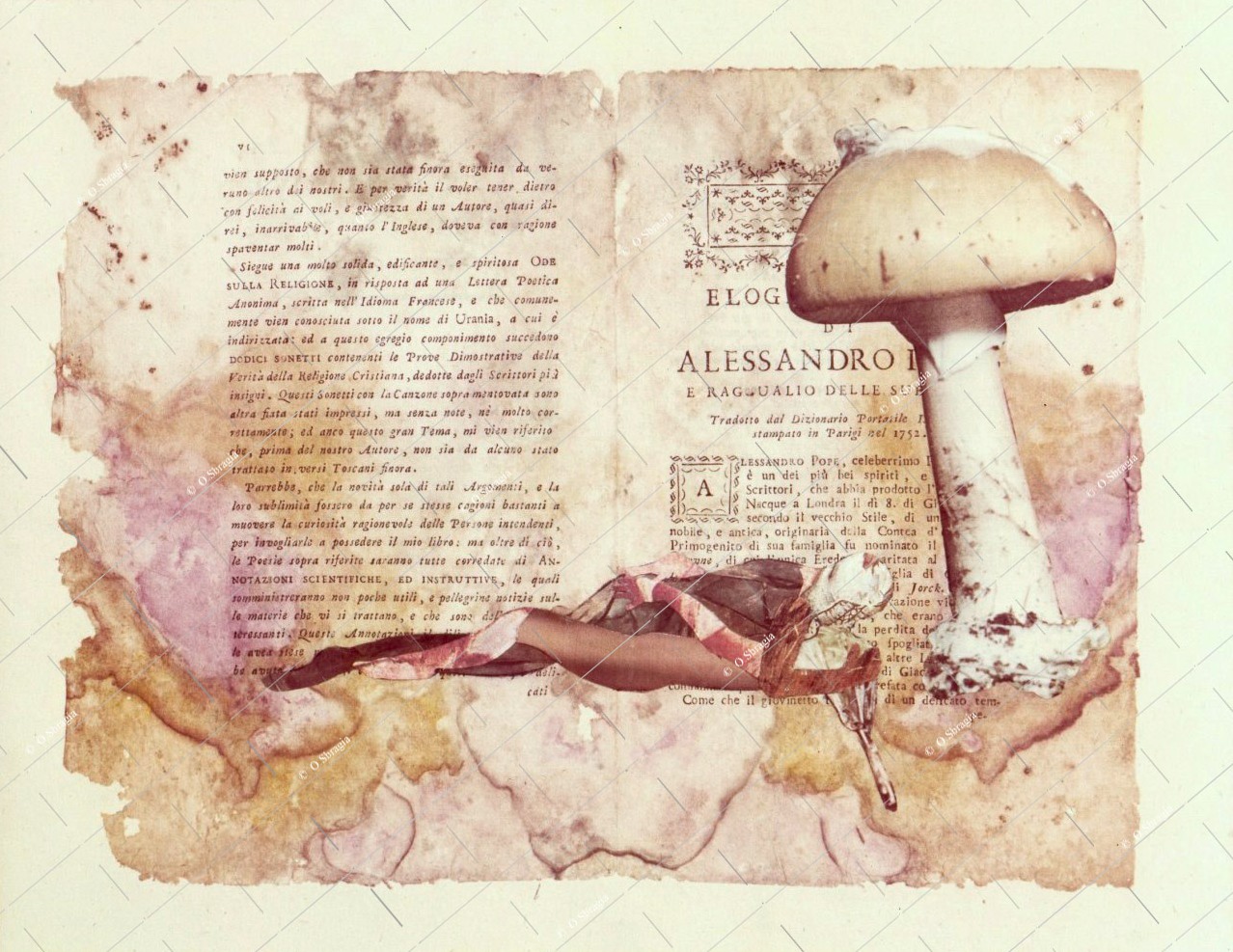

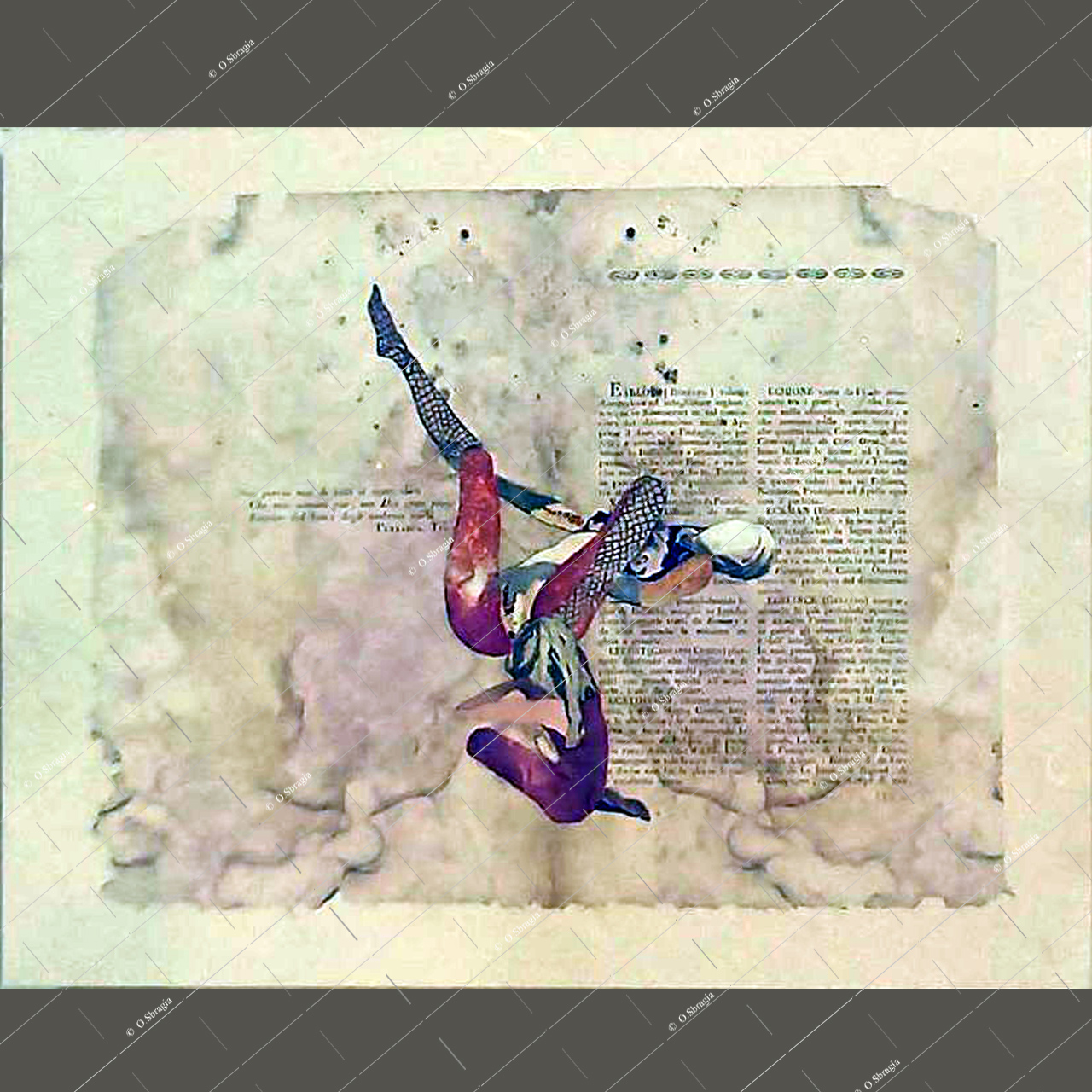

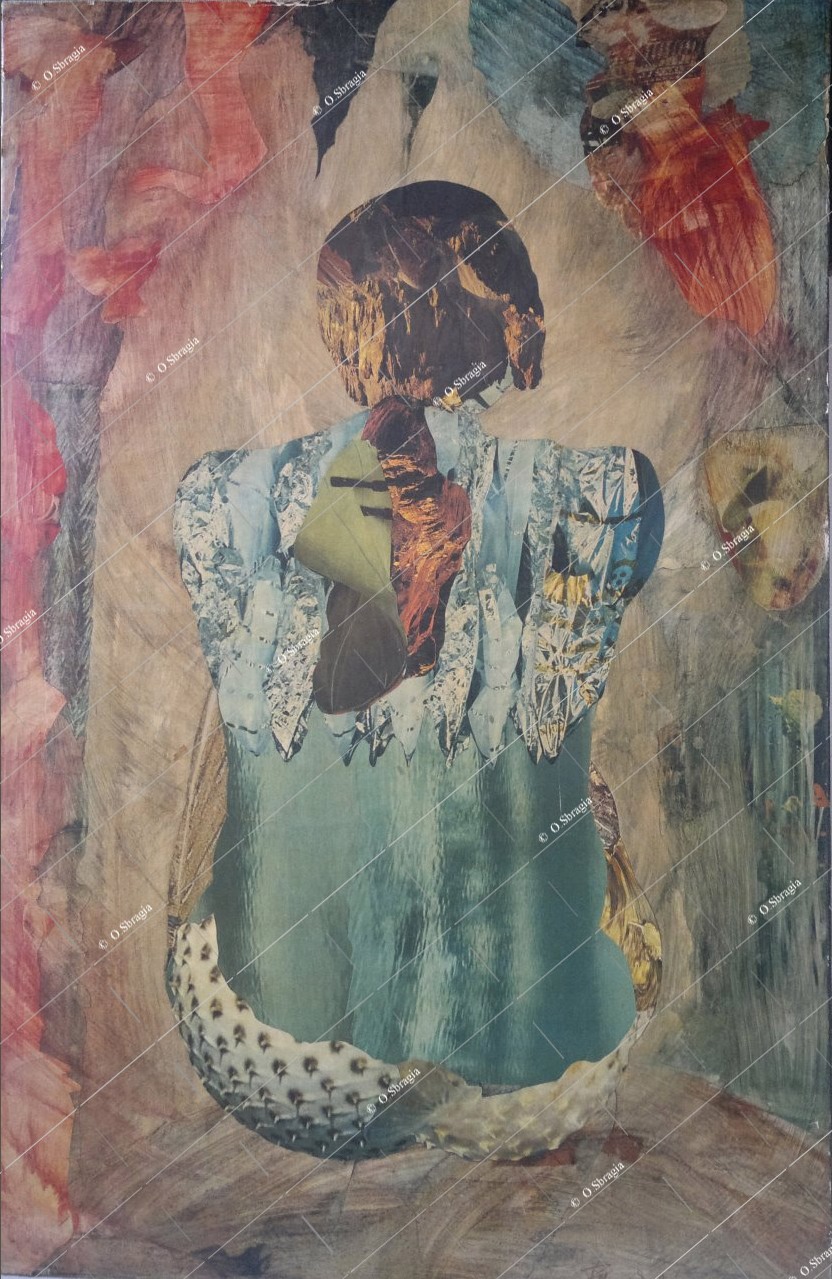

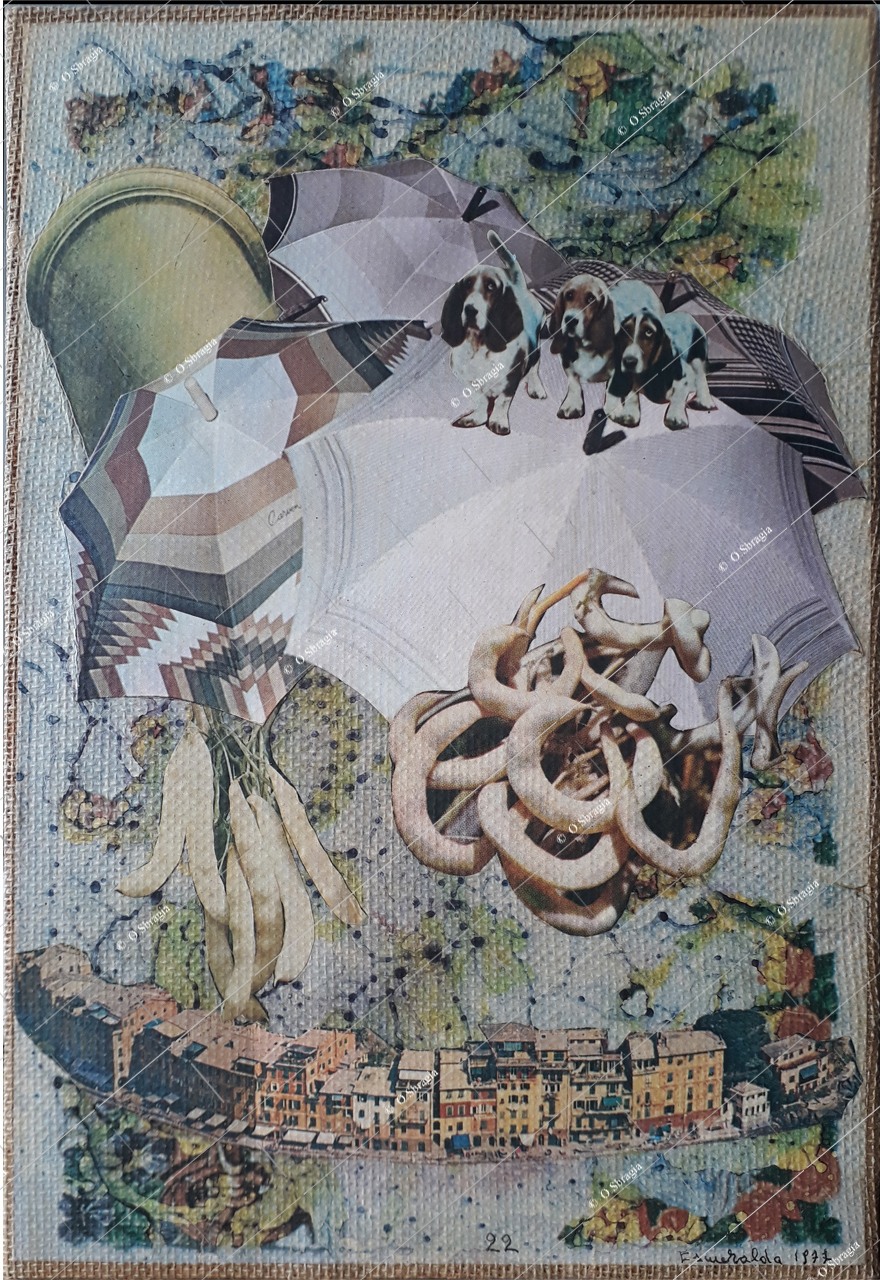

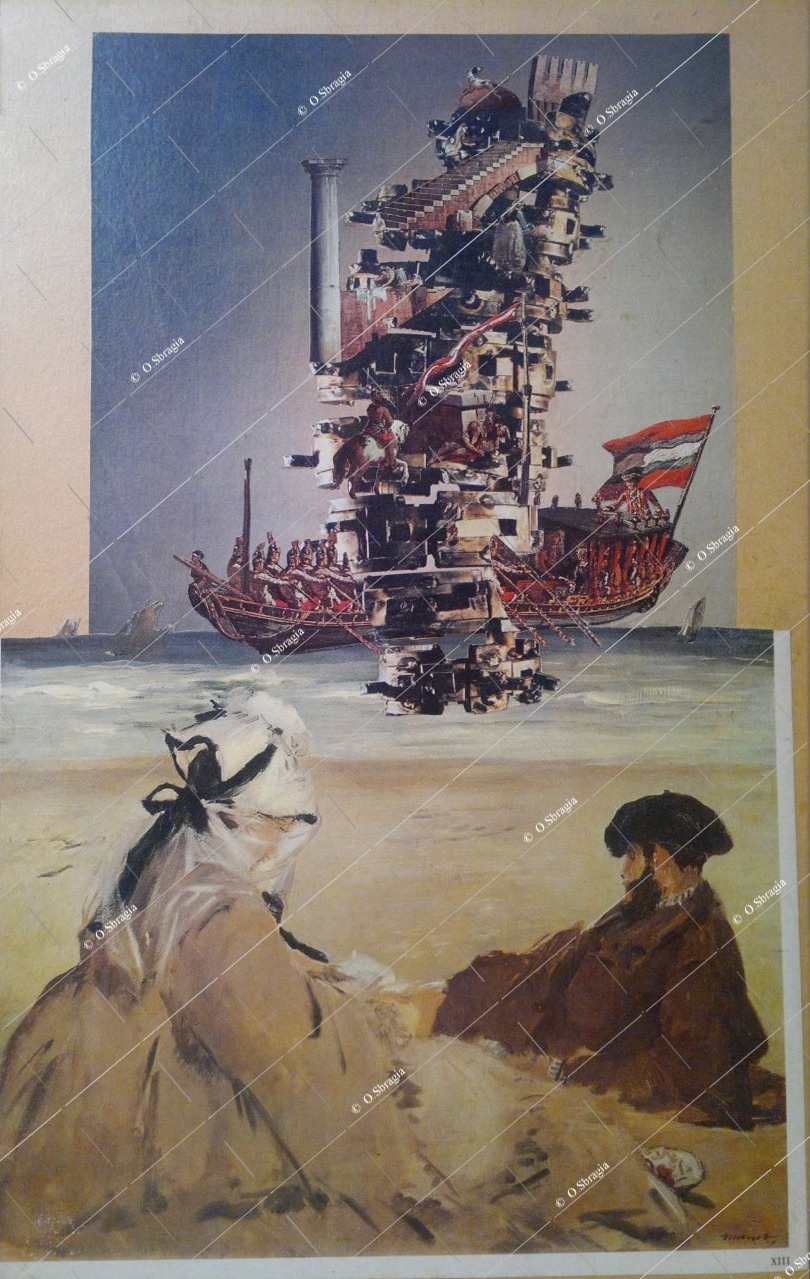

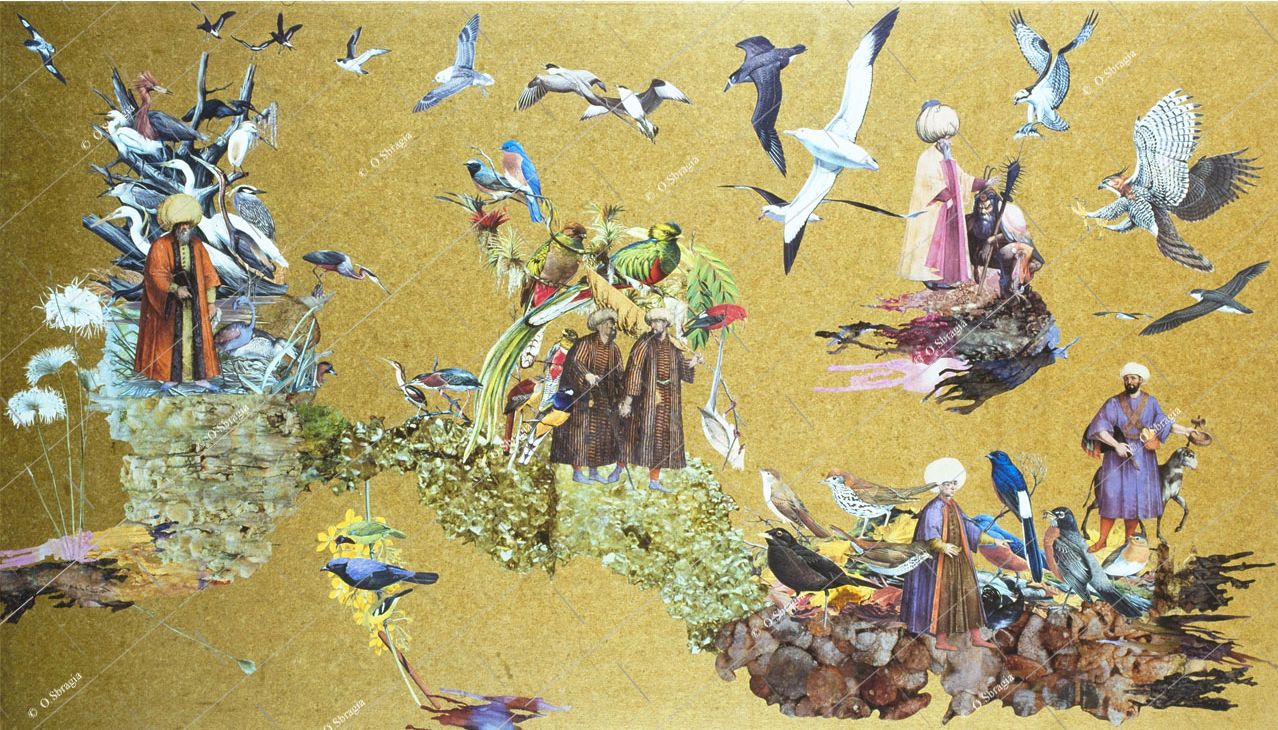

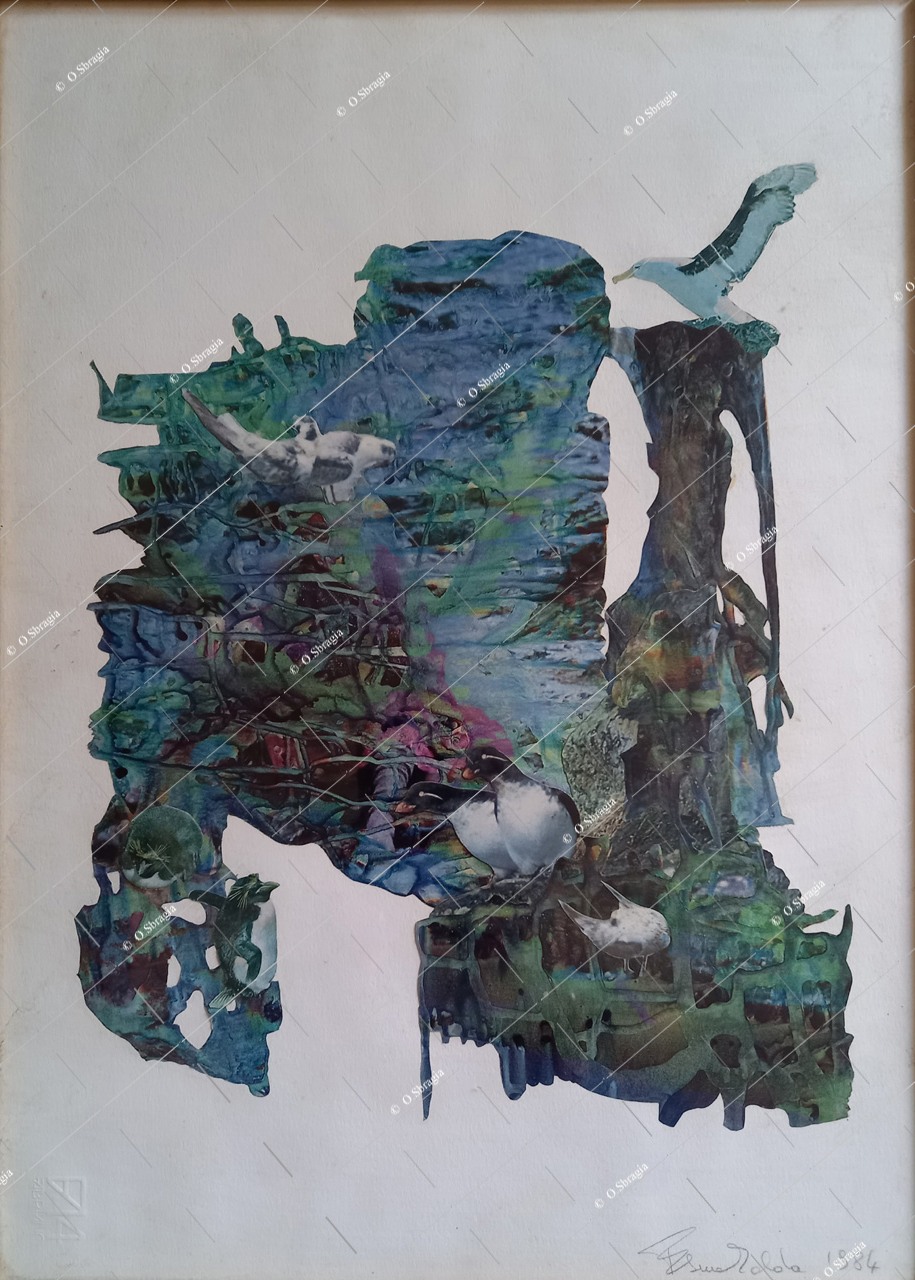

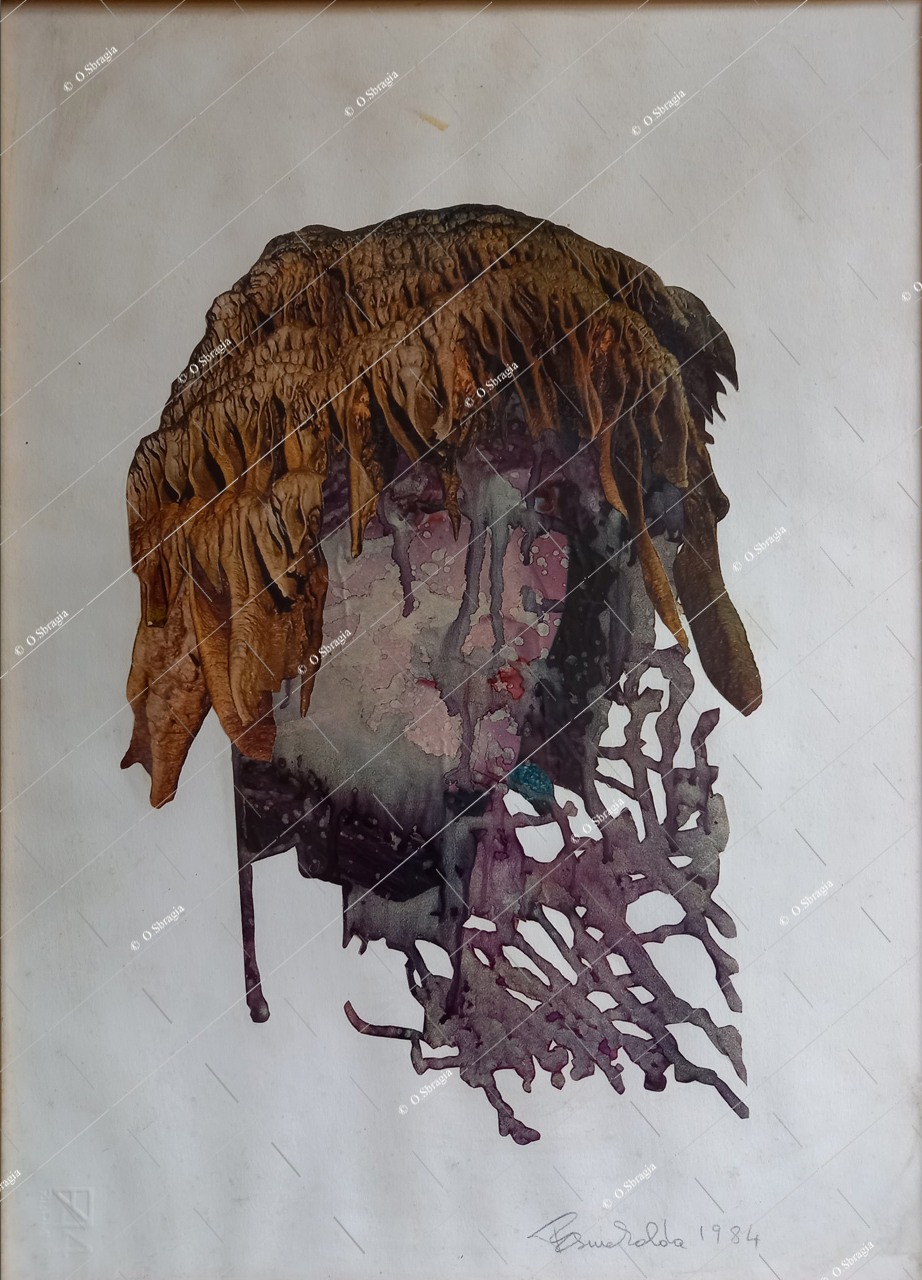

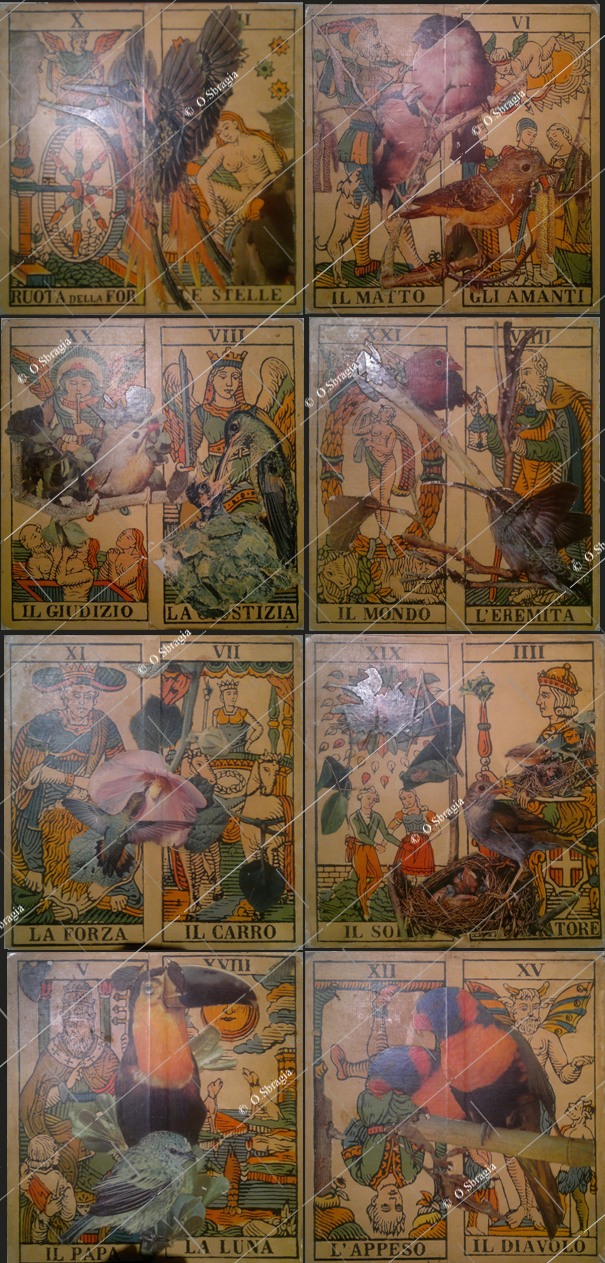

I have always looked at those collages, in fact, not as works of art but as the expression of an aspect of her personality; a mysterious world,

a little crazy and at the same time inscrutable, translated into objects; certainly decorative but also often disquieting or provocative.

This 'intimate' look at her work was probably suggested by the same attitude she had in the family. Notwithstanding the fact that Collage

has been the fil rouge of her life, it was never presented to us children as a profession that found confirmation in a corresponding economic

value given also her total lack of any managerial or business know-how.

I do remember, however, that during my childhood what I perceived as the dominant thread in the world of figurative art was that of abstract

expressionism; apart from that no other artistic expression was possible or credible.

The result of all this, in addition to our habit of seeing incredible collages continually emerge from her scissors, is that they have always

been observed, appreciated and loved more as my mother's stuff than as works of art.

1958, Rome, with my brother

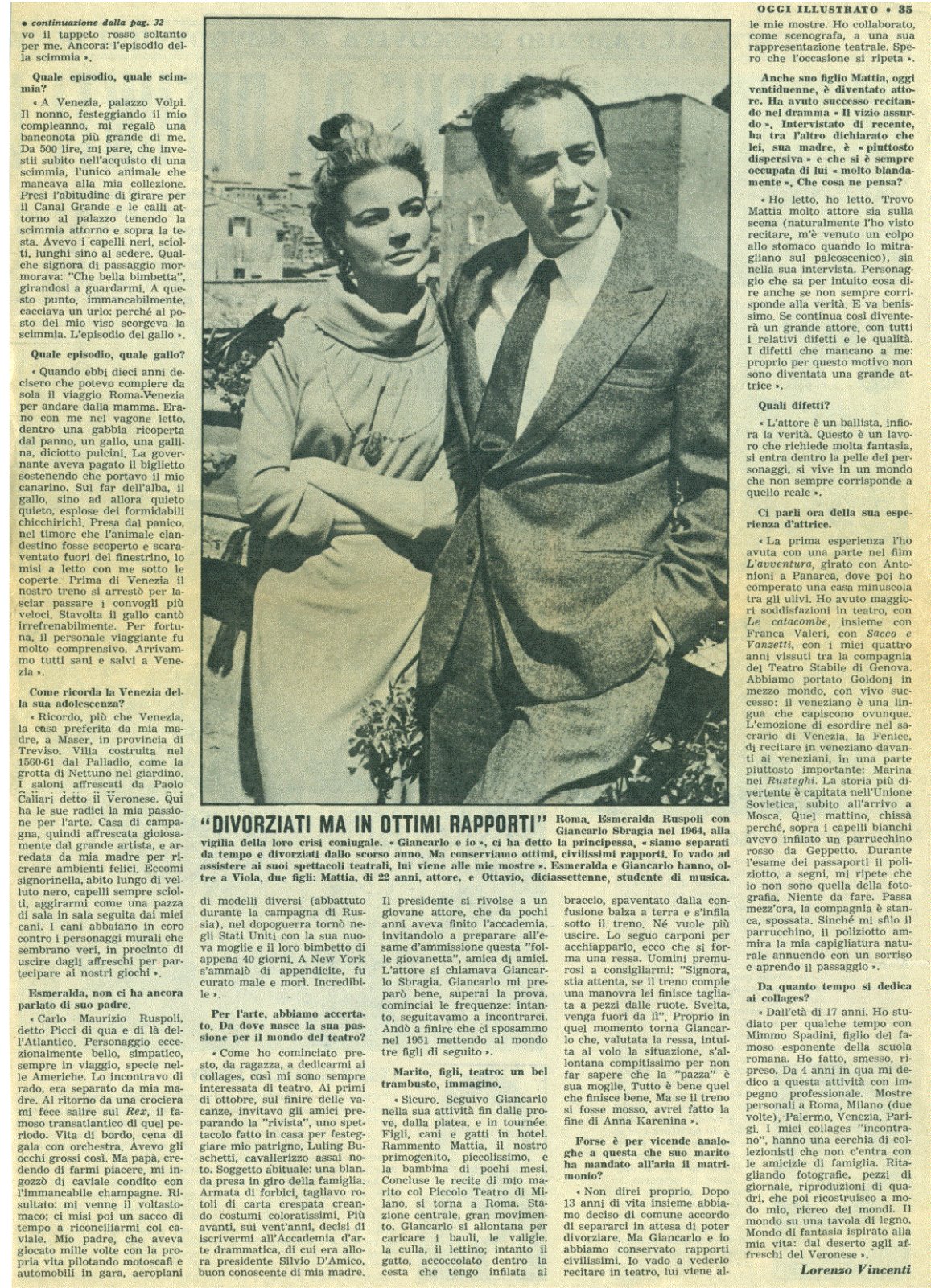

1972, Rome

The image that I have of her working during her lifetime has remained unchanged: seated on an old wicker child's chair (always the same one,

one of ours) in order to be at the right height, bent over the collage she was working on with the ever-present scissors in her fingers (always

the same ones given to her by the obstetric who had assisted at one of her births), around her a great confusion of magazines, art books, prints -

some cut up, others whole, in the middle of which she would fish out with perfect intuition the page containing the desired image.

The pleasant aroma of paste in the air, that white Vinavil that I liked so much.

My mother handled the scissors with skill and speed, chatting amicably with whomever came to see her as women of the preceding generation had done

when they were knitting. My memories as a child and as a young man return to this intimate atmosphere: the creative process of my mother's stuff.

Thirty years after her death I began, thanks to my guests, to look at my mother's work as "works" which today, I think, would find their

historic artistic place in a more variegated world of art.

My wish therefore for the visitor to this site is to enjoy this journey into the extraordinary world of Esmeralda.

Biography

Biography

For the biography of the early years of her life, it is better to listen to Esmeralda's own words:

[ full text in Vogue Decoration, December 1986, see

"Critiques" in this site ]

My name is Esmeralda Ruspoli. I was born in Rome on 24 June 1928 on the third floor of what once was Palazzo Volpi on Via Quattro Fontane, at

six o'clock in the morning, the daughter of Marina Volpi

and Carlo Maurizio Ruspoli. Carlo Maurizio in honour of

Talleyrand, the famous ancestor

of a paternal grandmother. My early childhood was spent with an English nurse, servants, chauffeurs and automobiles in townhouses, country homes

and villas in the desert like any other child belonging to a privileged class of the world. Perhaps that was when my vocation for collage was born.

When I was ill for a long time in bed because of influenza or the measles, I remember that someone brought me some soft material made of flour and

water. I don't think that I thought I was making works of art then, but I can still feel the soft quality of that substance. That was also the sensation

of the feathers that my mother's maid used to fill the cushions, and in the kitchen, the rice that I took out of a box and let run through my fingers!

Touch. The apprenticeship of my hands evolved with a respectful lightness, almost a caress, letting me discover objects simply by touching them.

Animals, materials, hair, flower petals, skin, water. A dreamer since childhood, images have always had a rather mysterious life in my soul and

I encounter them in the faces of others. A person in a painting, a tree in a photograph, an animal in an engraving, a landscape behind a painted

Madonna, architecture, automobiles, colours: in fact in everything that is printed on paper, I find fragments of a dream that belongs to me.

I learned to look for them, to cut them out, to assemble them and paste them onto a variety of supports. When I work, I use my hands for pasting,

but also to make the paste, and then I place the pieces of paper together in order to obtain a homogeneous result.

My life? Elementary school at the Villa Maser of

Andrea Palladio where I lived with my mother, and the paper dolls' houses made in an exercise book.

1935ca, Villa di Maser

Easter vacation at Tripoli in the enchanted garden of my maternal grandmother watching nature which told me marvellous stories. The summer at

Venice where in every corner of Palazzo San Beneto, I would encounter the fairies of my imagination in the penumbra of the salons; and where

my monkey played amid plants and climbed the courtyard walls, amusing itself by chasing the doves. Later, secondary school at a lycÚe in Rome

with rather insufficient results [...],

After starting lycÚe in Rome, towards the end of the Second World War she was sent to a private school at Lausanne. She did not receive a regular academic education

regarding the figurative arts. For a while she studied with Andrea (Mimmo) Spadini and, thanks to family contacts, met many artists among whom Titina Rota, Fabrizio Clerici,

Lila De Nobili, Leonor Fini, Luigi Tito . In Milan, she started to take a nursing course, probably following the usual path

destined for the daughters of Italian high society, until she finally managed to convince her mother to let her enrol in the Academy of Dramatic Art in Rome in order

to pursue her other great passion: acting.

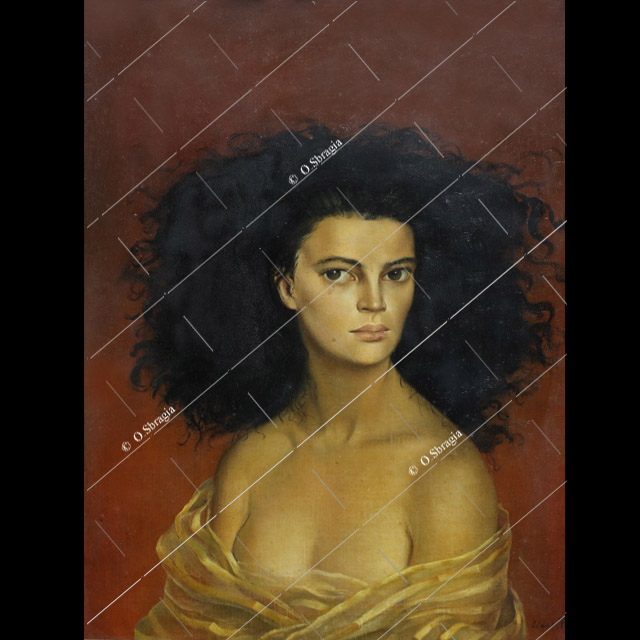

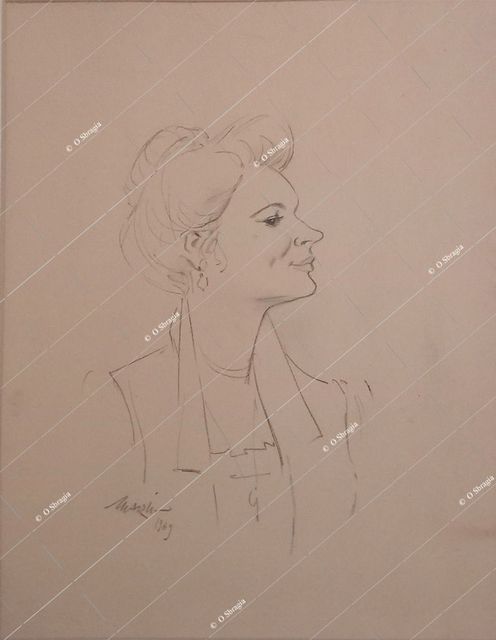

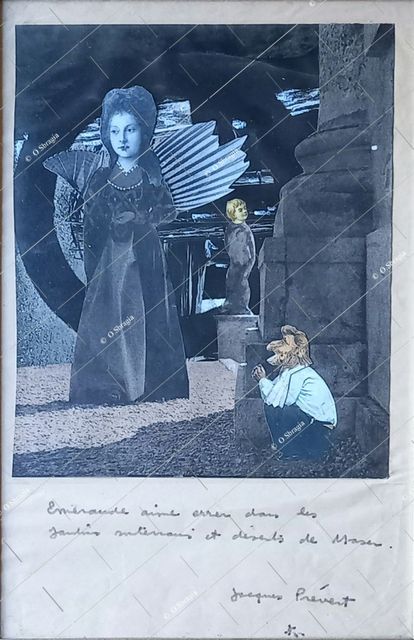

Fabrizio Clerici, 1950

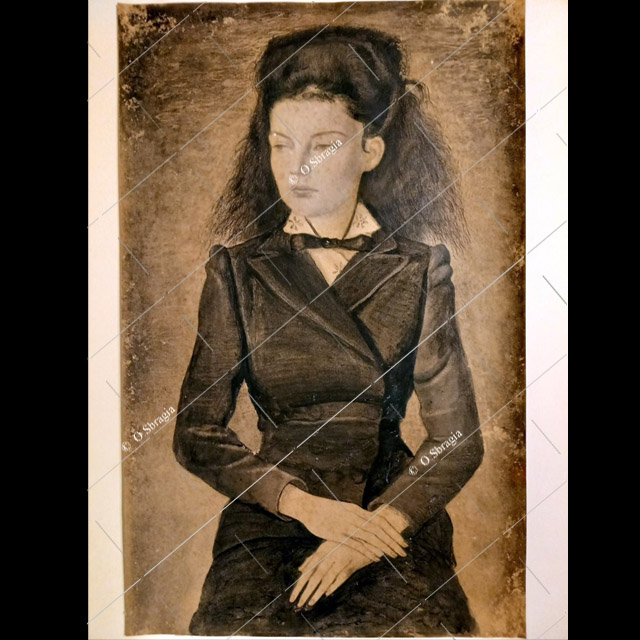

Fabrizio Clerici, 1943

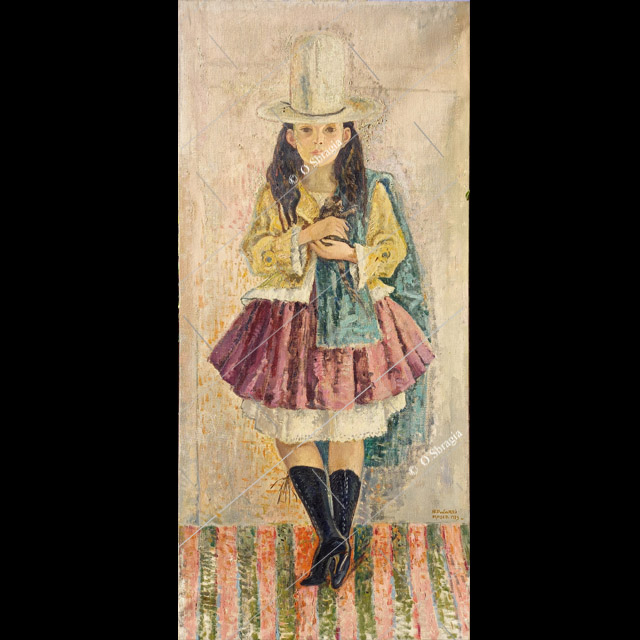

There, she met Giancarlo Sbragia. They married and had three children.

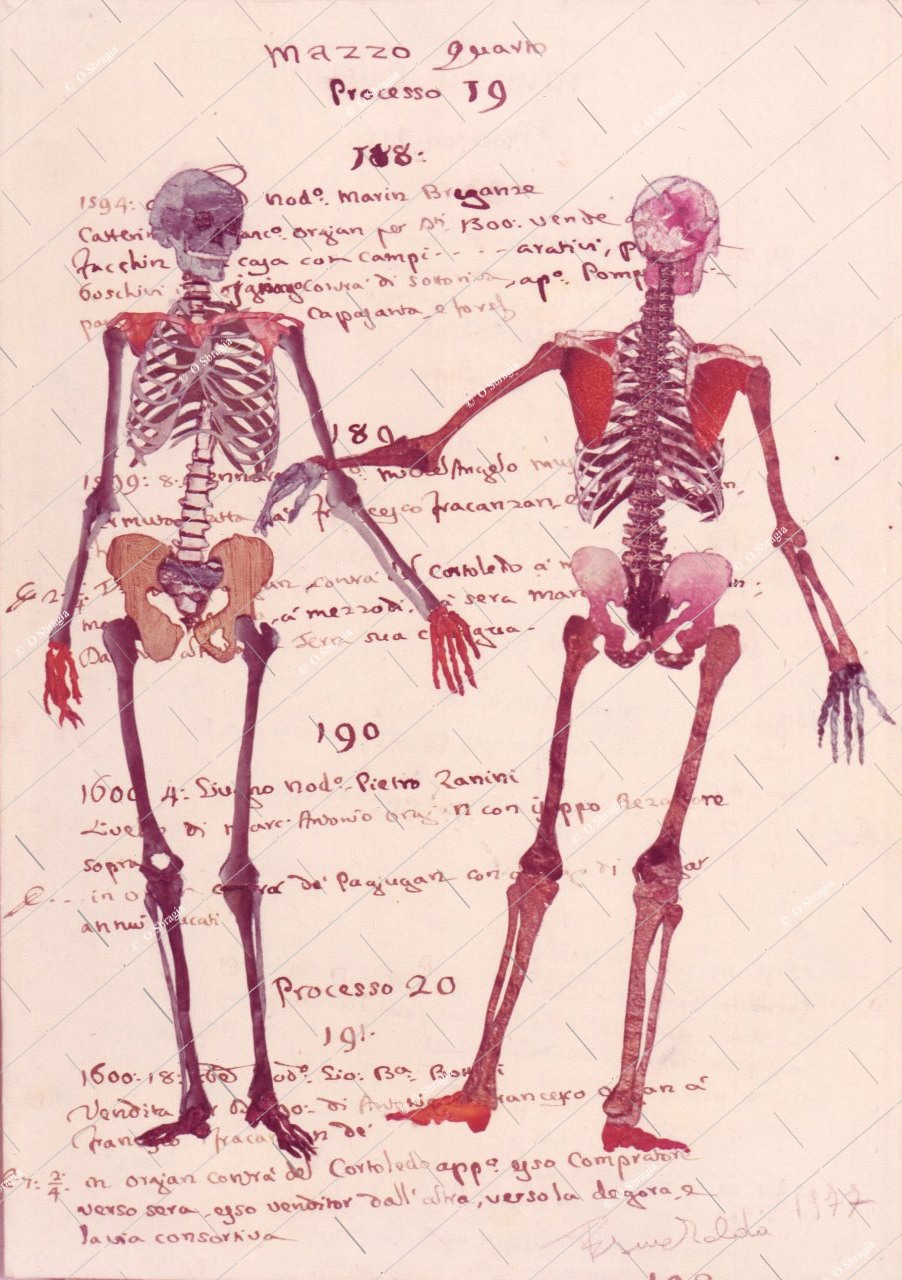

The early years of her marriage were occupied principally with her family and the collages. She took painting lessons from

Fabrizio Clerici, and then in 1959 returned to acting, interpreting the role of Patrizia in Michelangelo Antonioni's film L'Avventura. Parts in other films followed,

along with work in television films and theatrical companies.(IMDb)

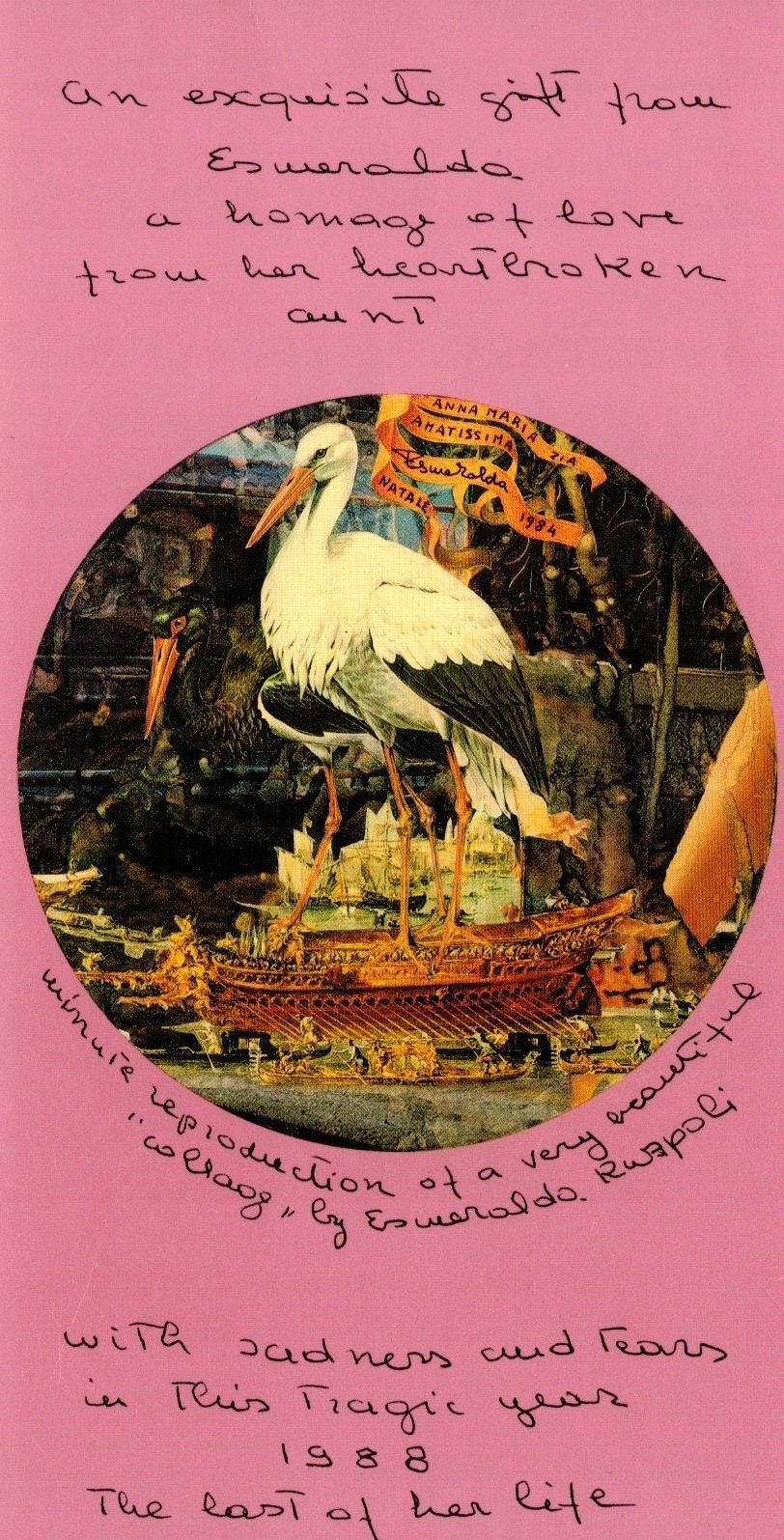

In 1975, she decided to stop acting and to dedicate herself totally to the collages, an activity she had never really abandoned.

The last ten years of her life were divided equally between Venice and Panarea, the Aeolian island where Antonioni's film had been made in 1959 and where she had bought the land on which she

had built her home.

During this time she made innumerable works until the last day of her life.

She died suddenly when she was sixty of a cerebral aneurism.

She is buried at Panarea.

Exhibitions

Exhibitions

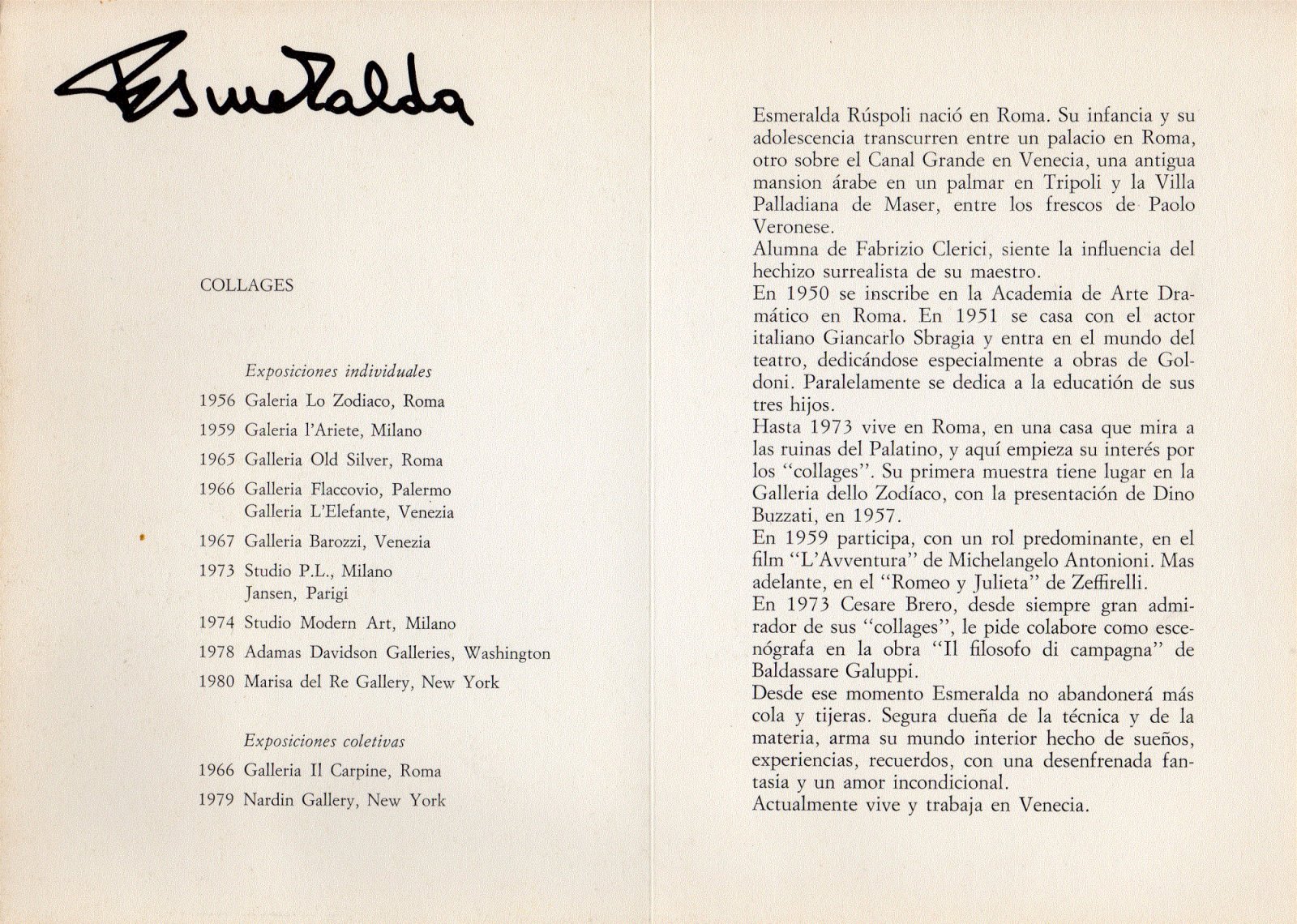

PERSONAL

1956 Galleria Lo Zodiaco, Roma

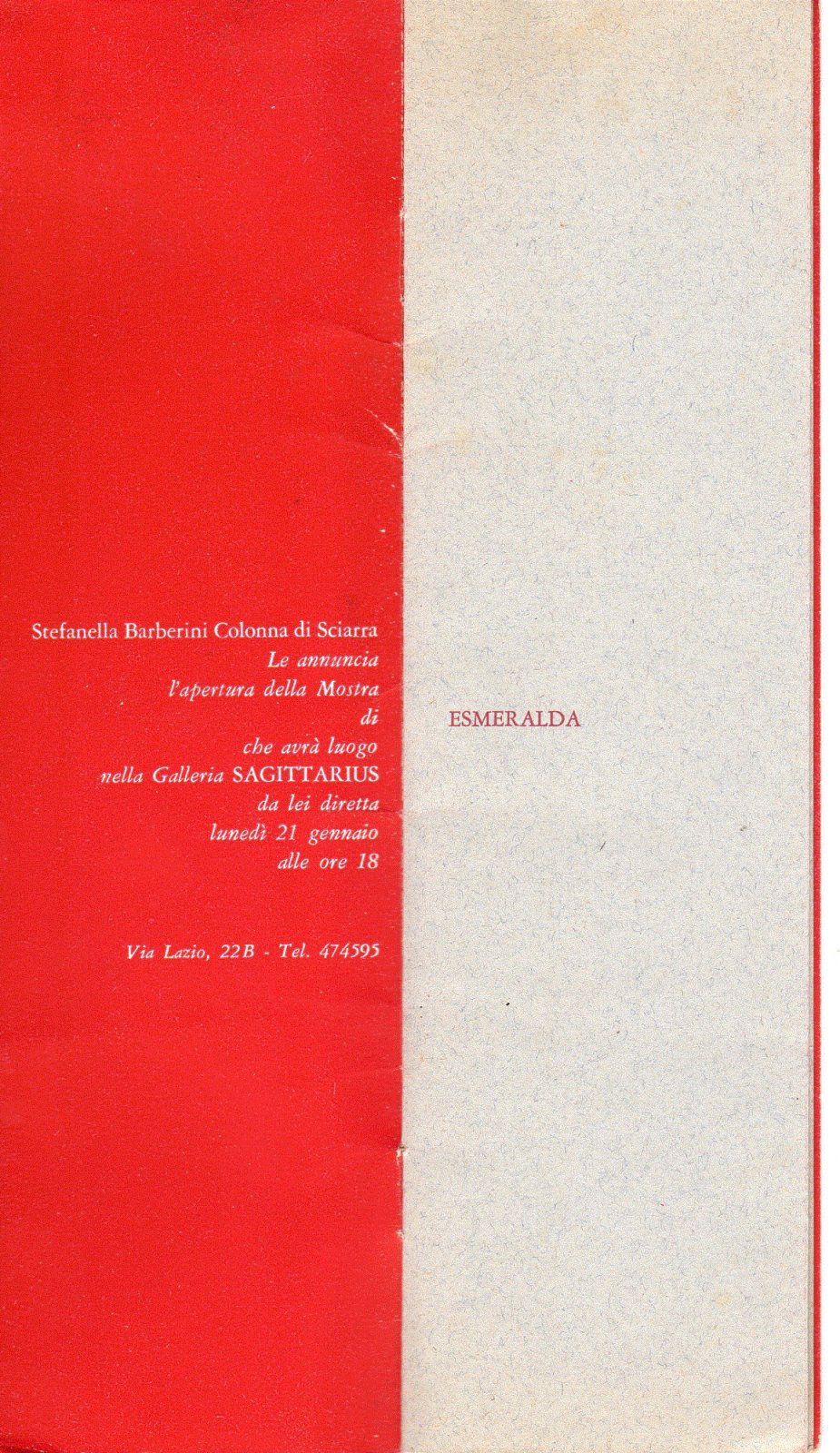

1957 Galleria Sagittarius, Roma

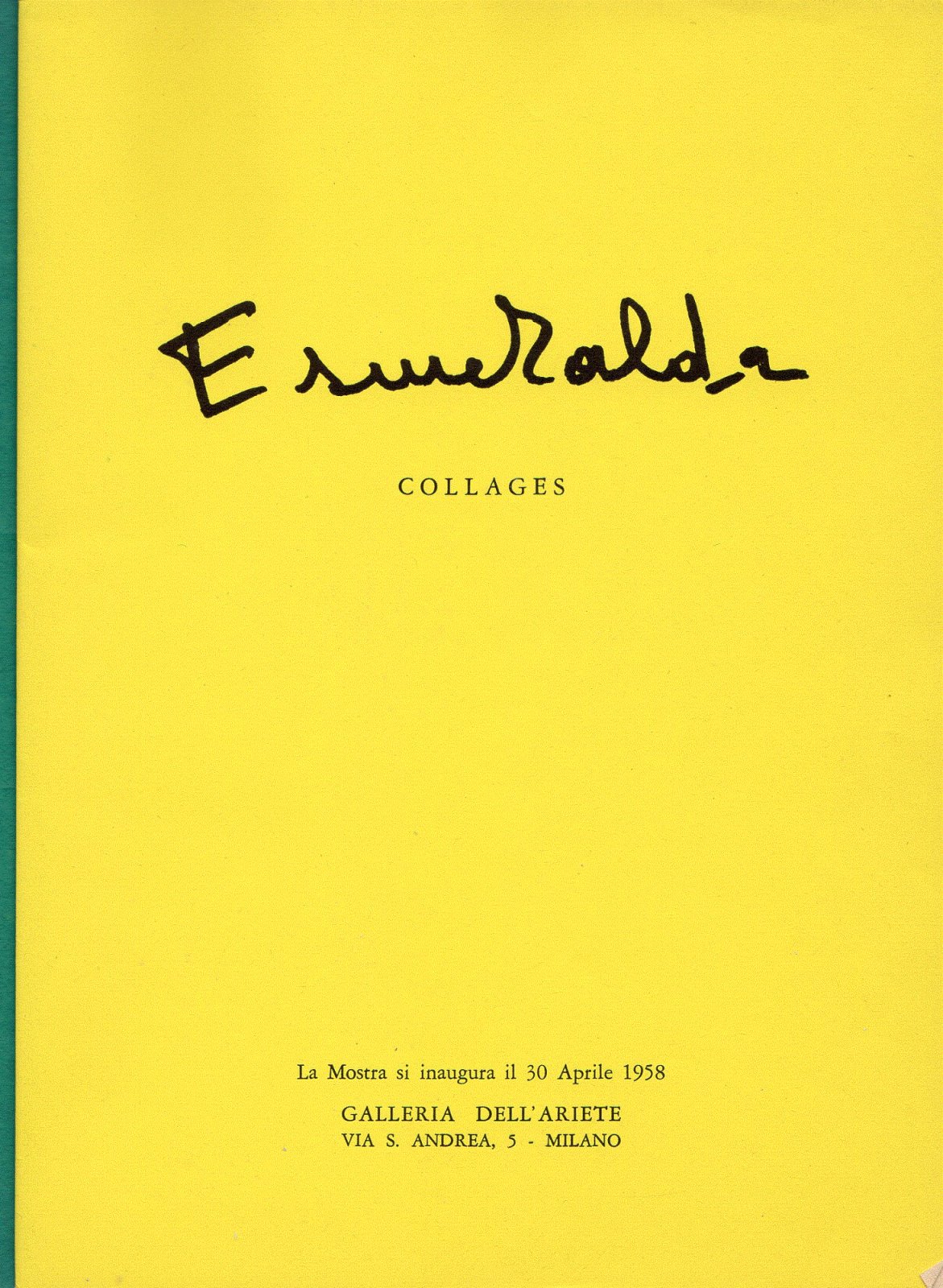

1959 Galleria l'Ariete, Milano

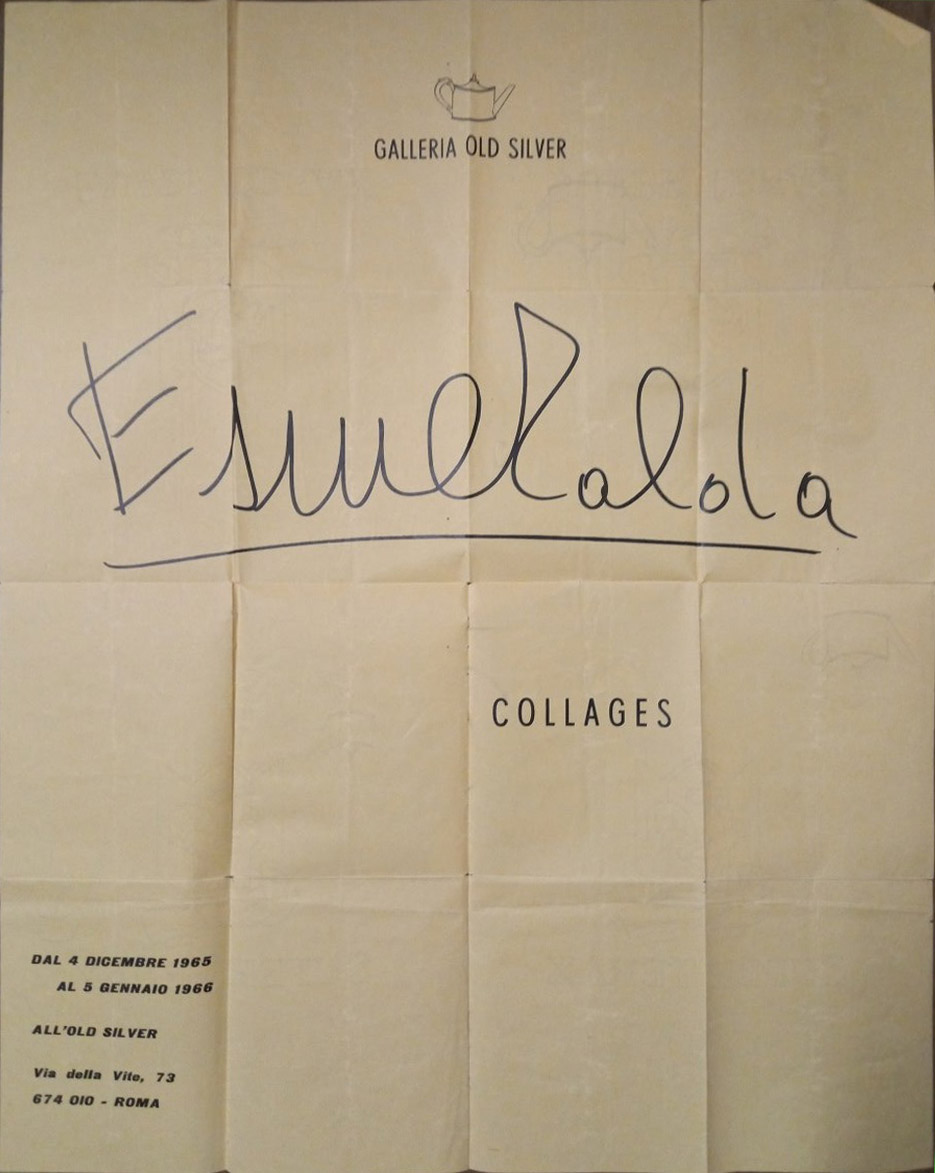

1965 Galleria Old Silver, Roma

1966 Galleria l'Elefante, Venezia

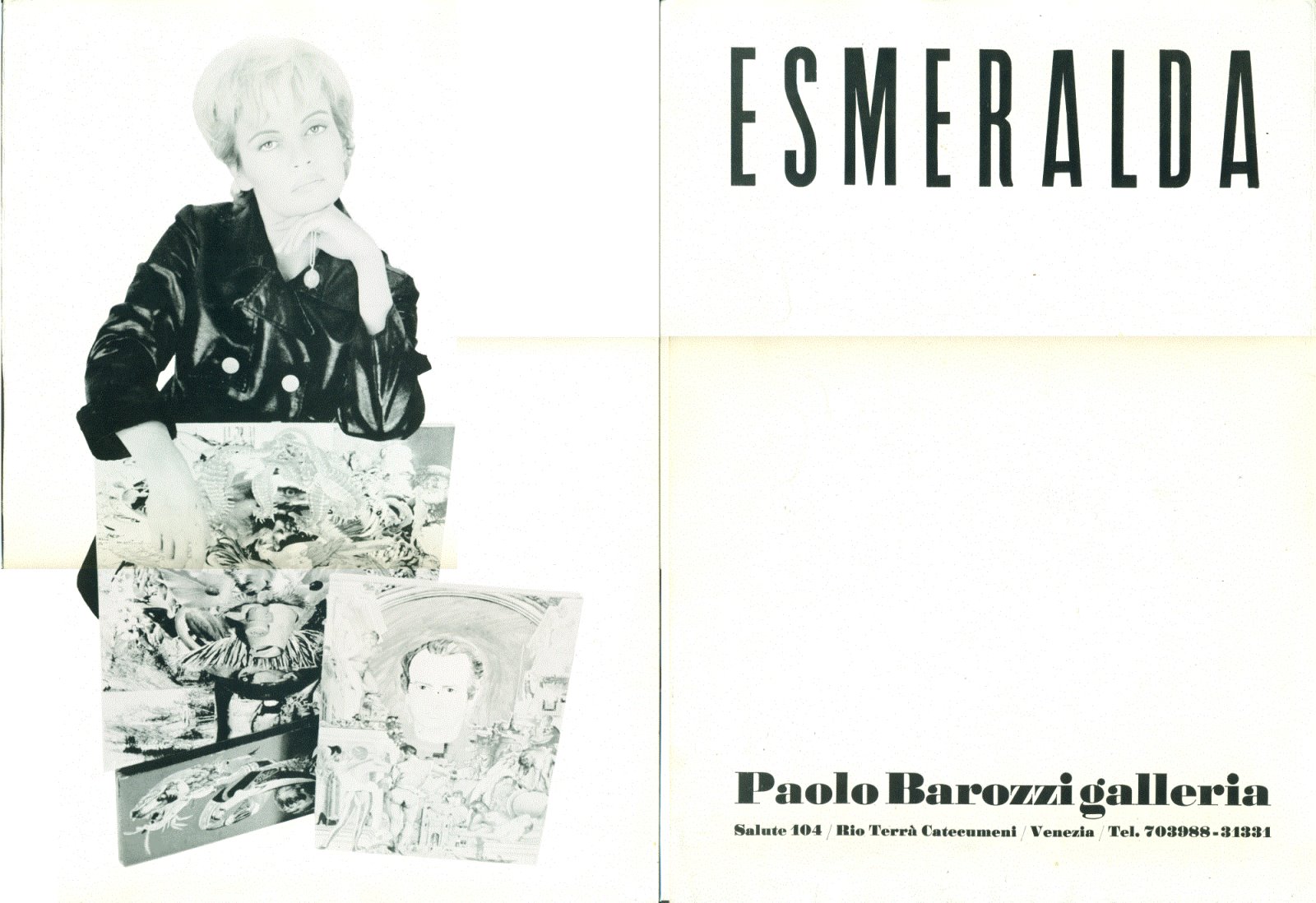

1967 Galleria Barozzi, Venezia

1973 Studio P.L., Milano

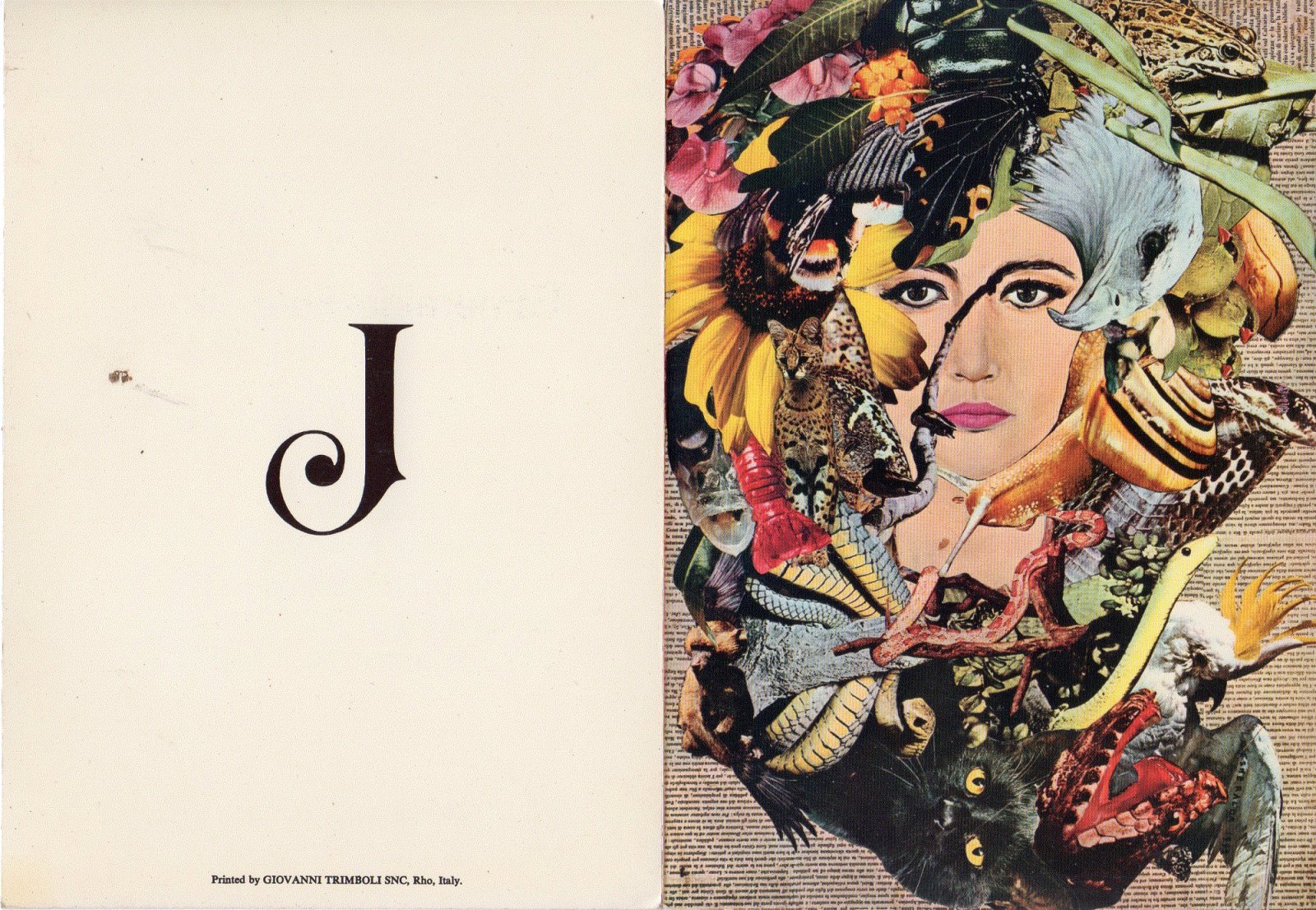

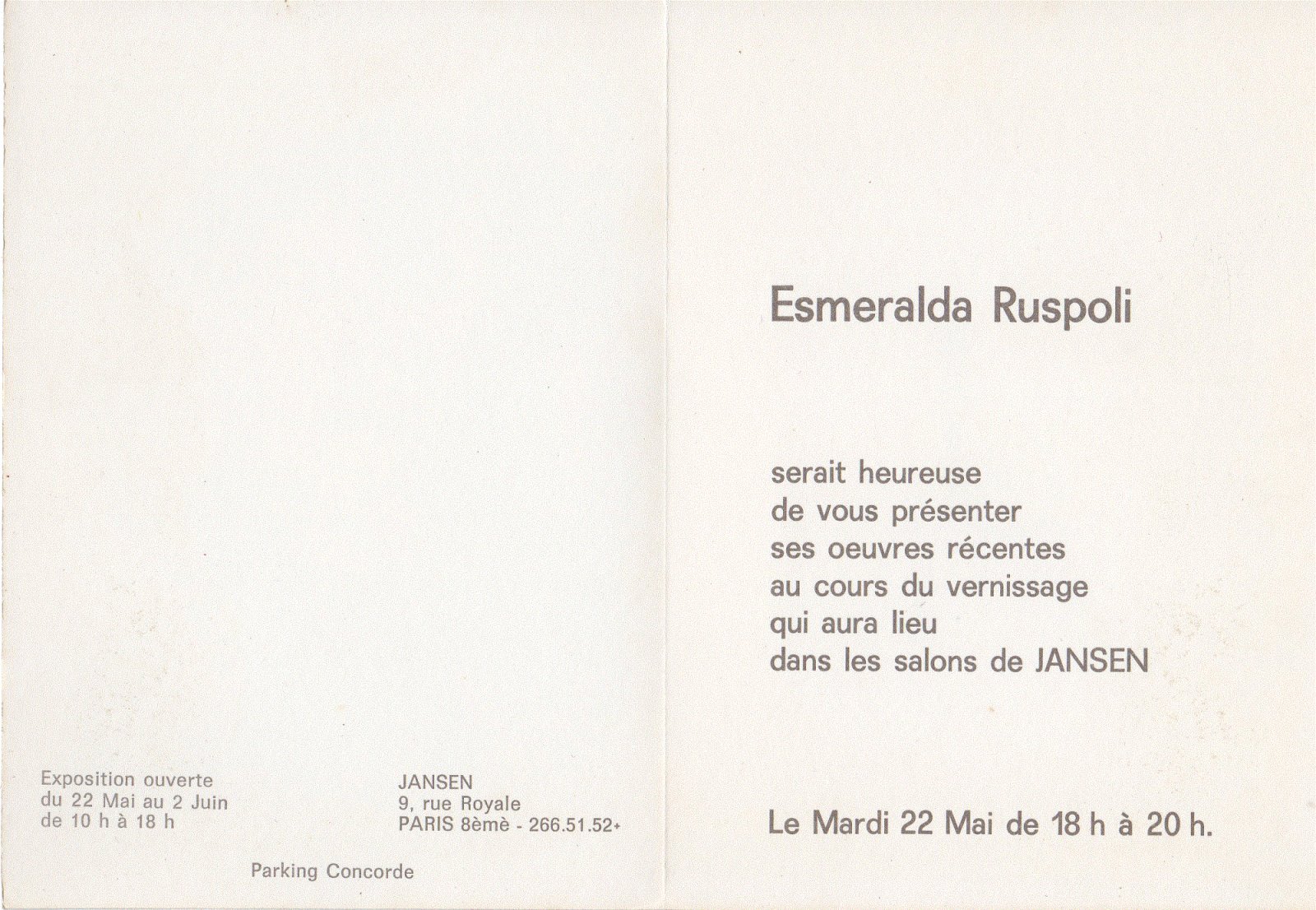

1973 Jansen, Parigi

1974 Studio Modern Art, Milano

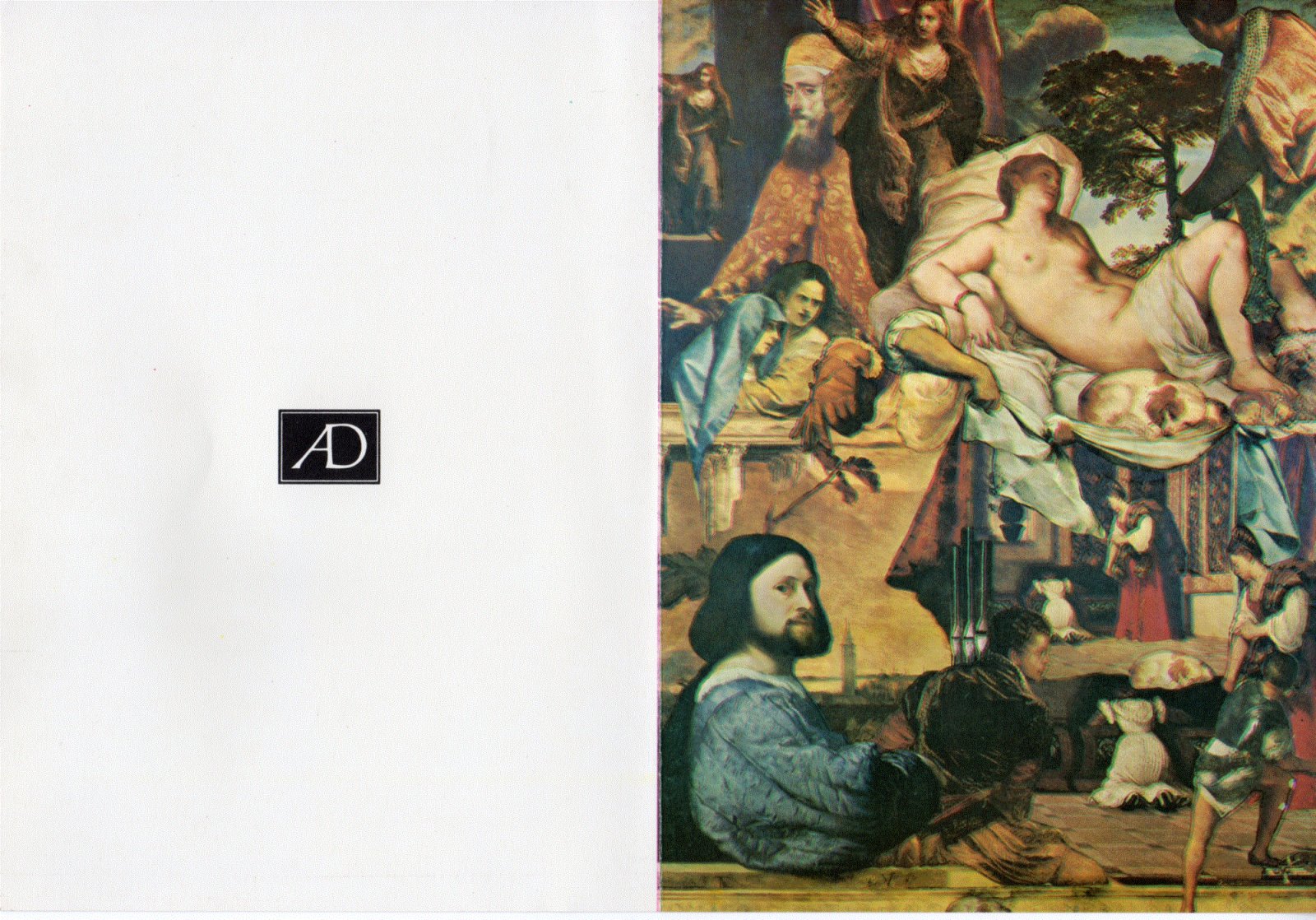

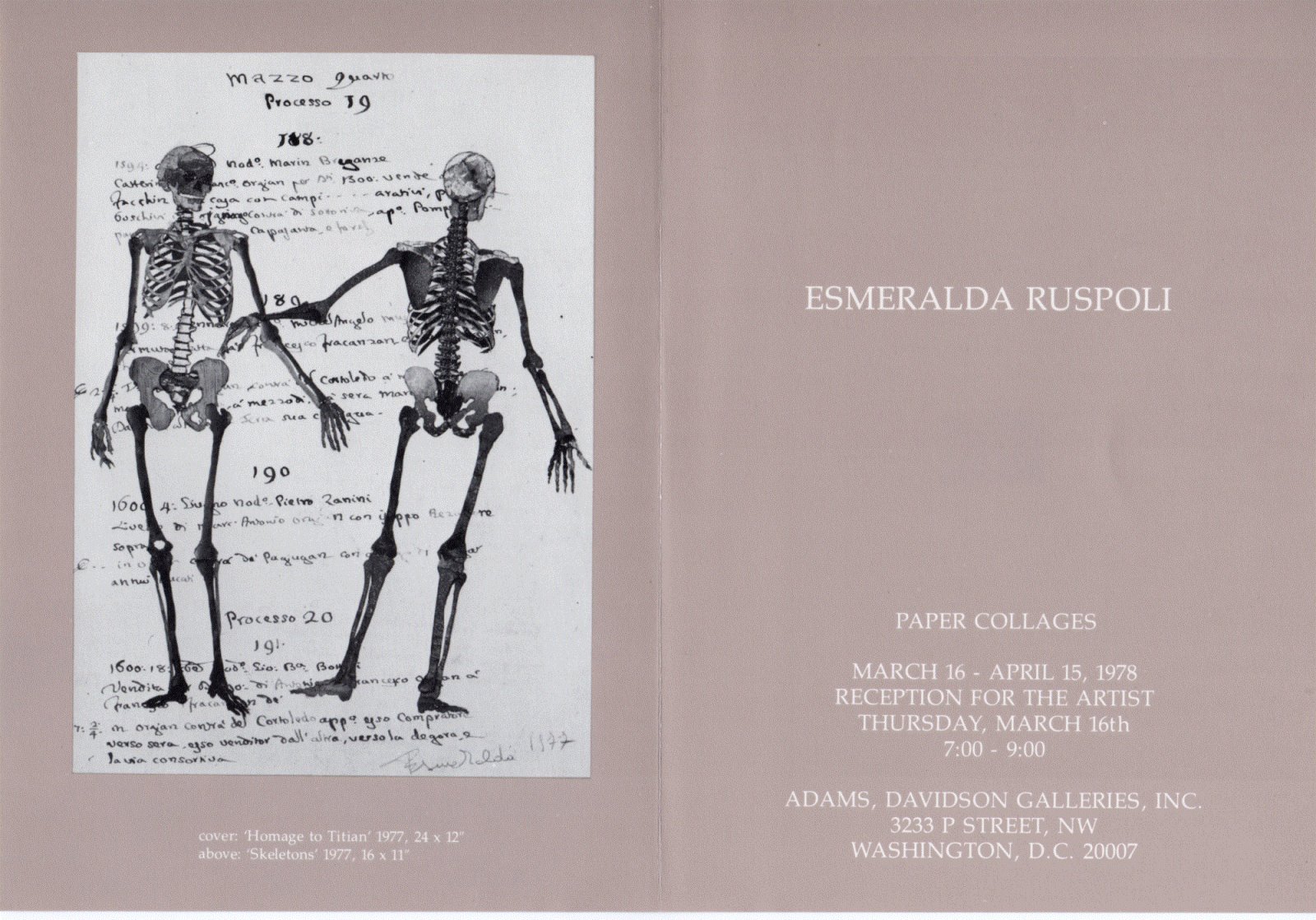

1978 Adams Davidson Galleries, Washington

1978 Nardin Galleries

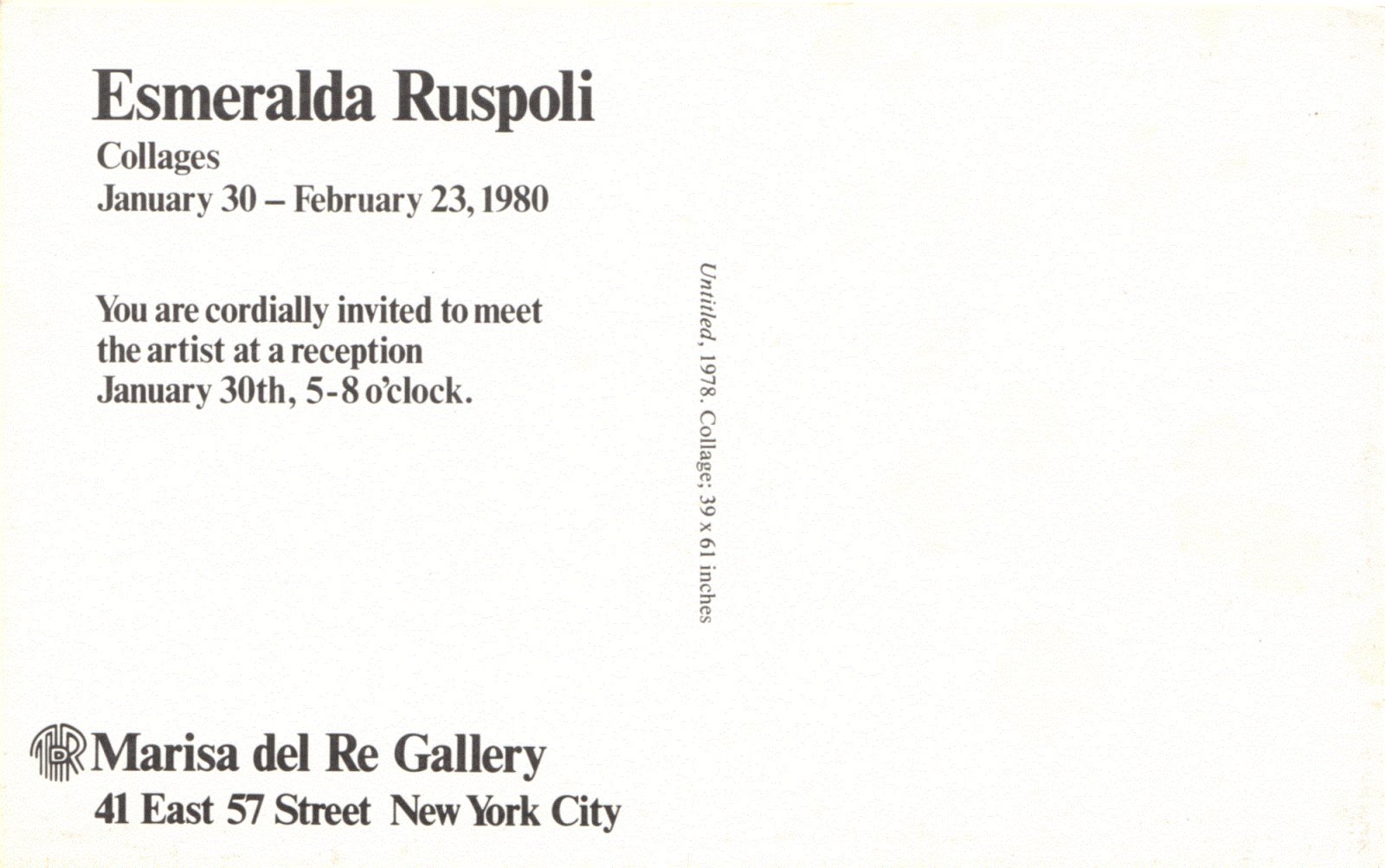

1980 Marisa del Re Gallery, New York

1980 Galeria Siglo XX, Buenos Aires

1982 Marisa del Re Gallery, New York

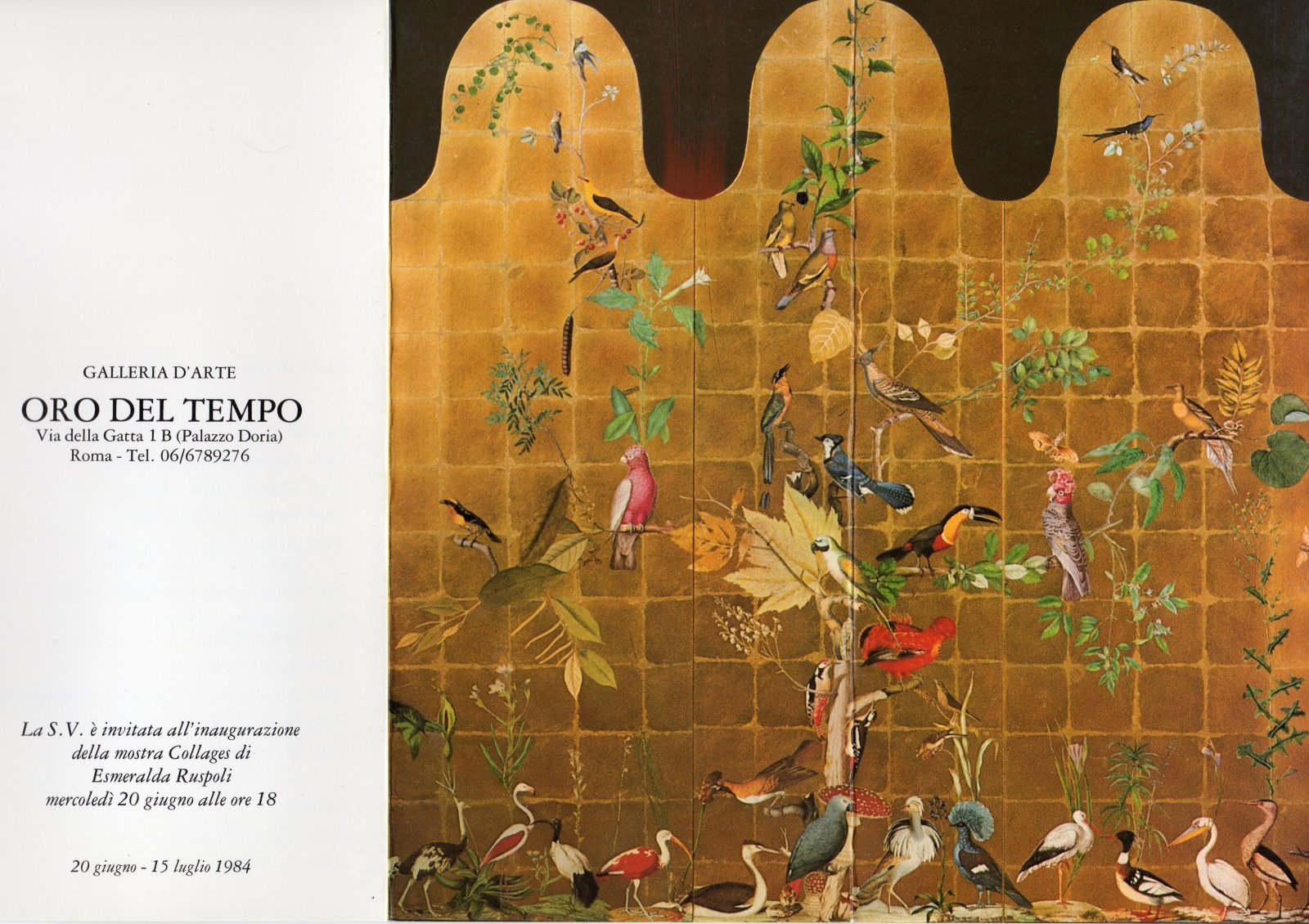

1984 Galleria Oro del Tempo, Roma

1984 La Goccia, Torino

1985 Ostium, Cagliari

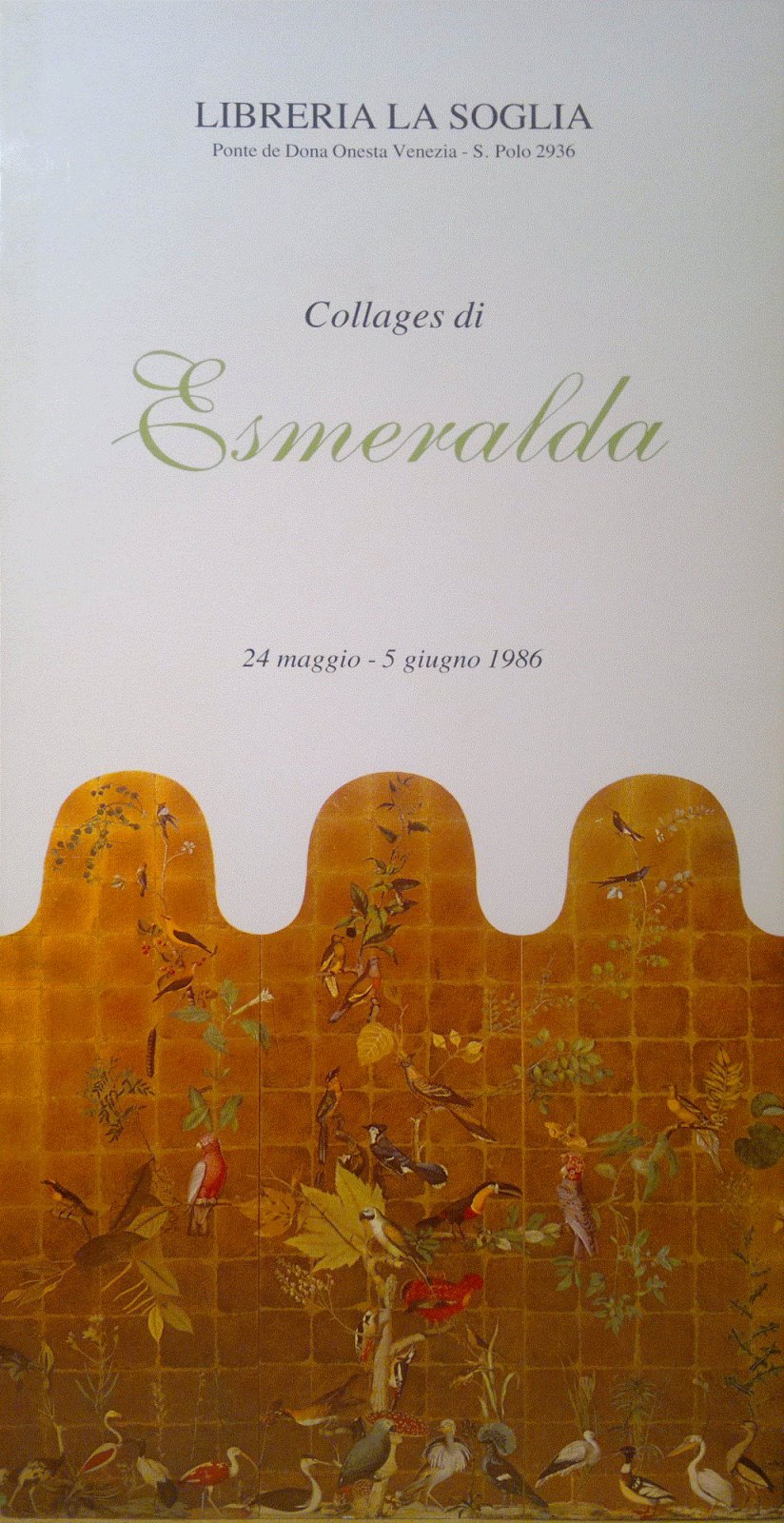

1986 La Soglia, Venezia

COLLECTIVE

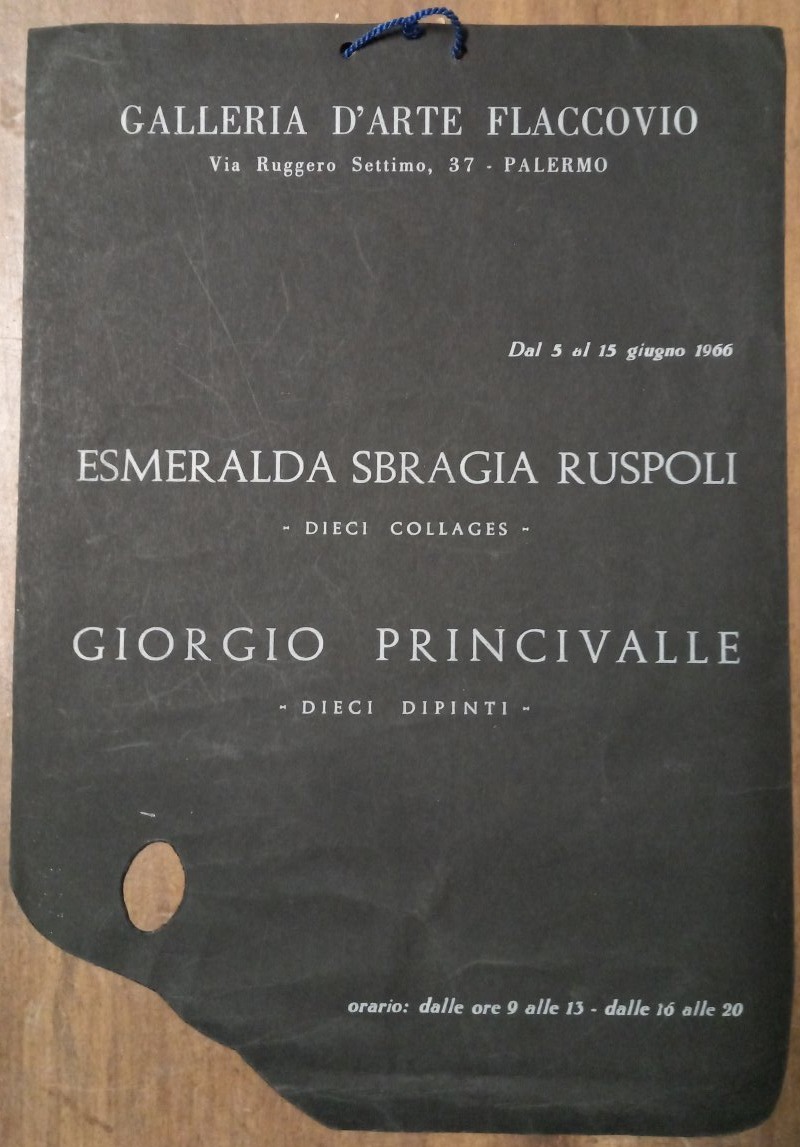

1966 Galleria Flaccovio, Palermo

1966 Galleria Il Carpine, Roma

1978 Nordin Gallery, New York

1985 Ai Privati Granai Solferino, Milano

[...see dÚpliants ]

[ hide dÚpliants]

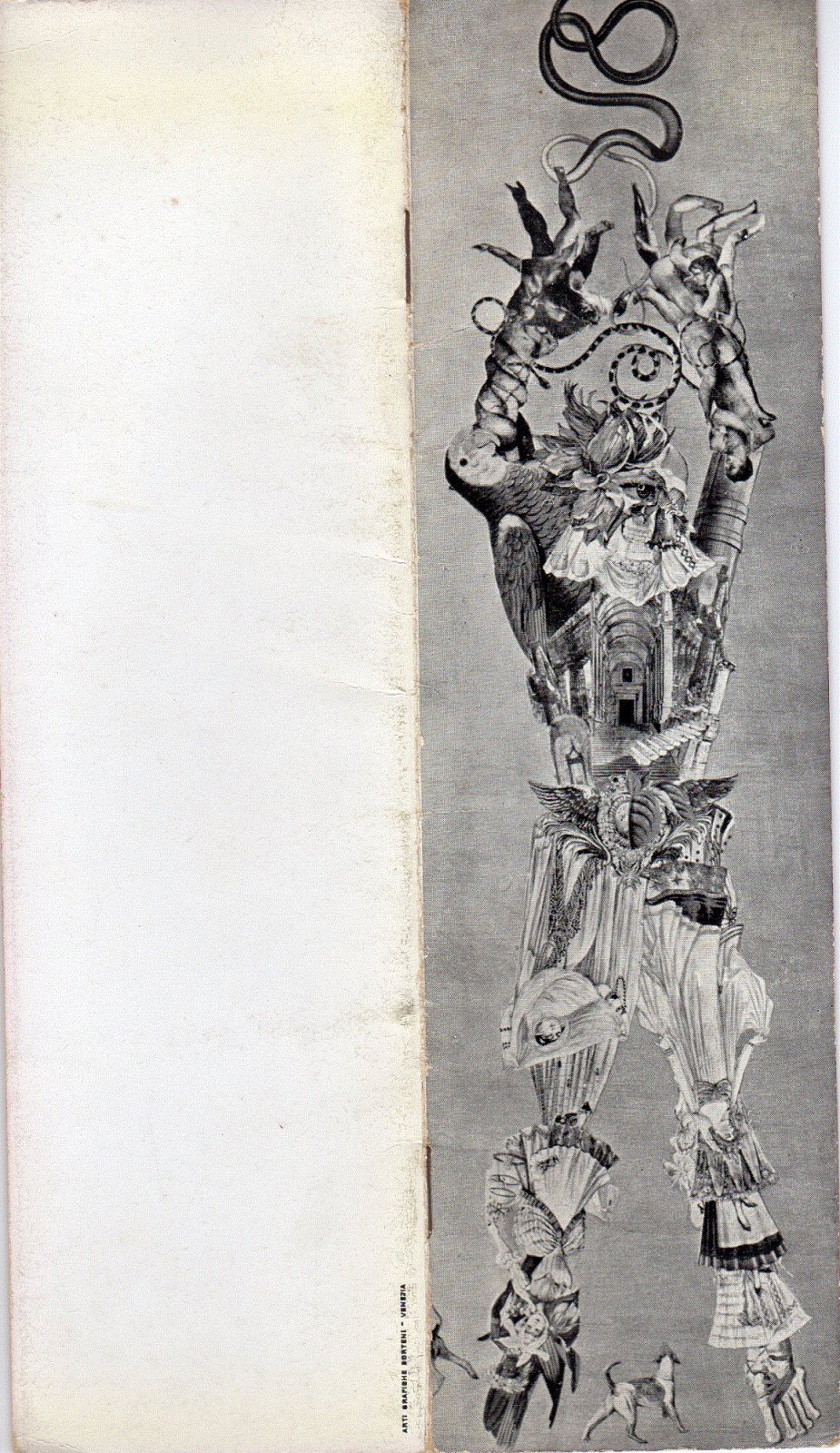

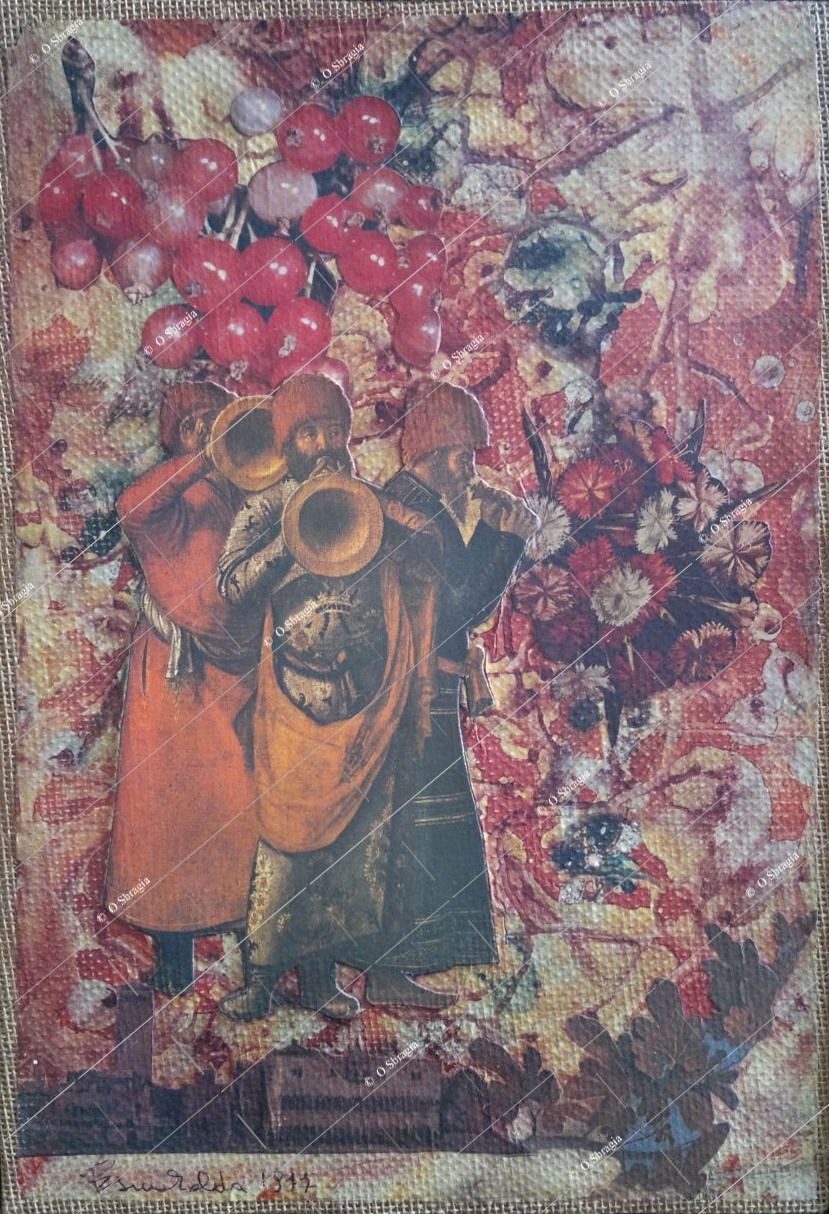

1957 Galleria Sagittarius, Rome

1957 Galleria Sagittarius, Rome

1959 Galleria l'Ariete, Milan

1959 Galleria l'Ariete, Milan

1965 Galleria Old Silver, Rome

1965 Galleria Old Silver, Rome

1966 Galleria Flaccovio, Palermo

1966 Galleria Flaccovio, Palermo

1966 Galleria l'Elefante, Venice

1966 Galleria l'Elefante, Venice

1967 Galleria Barozzi, Venice

1967 Galleria Barozzi, Venice

1973 Jansen, Parigi

1973 Jansen, Parigi

1978 Adams Davidson Galleries, Washington

1978 Adams Davidson Galleries, Washington

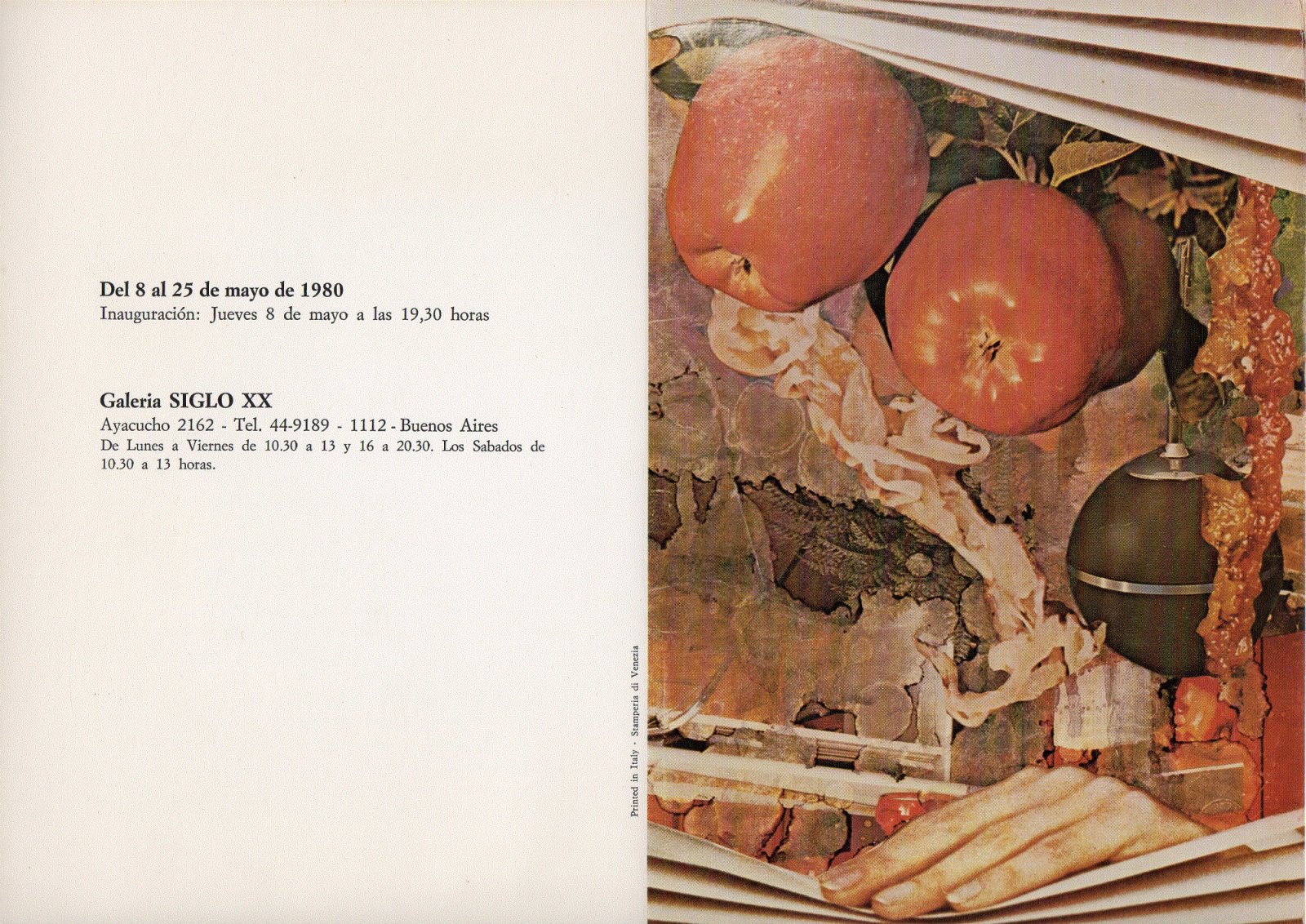

1980 Galeria Siglo XX, Buenos Aires

1980 Galeria Siglo XX, Buenos Aires

1980 Marisa del Re Gallery, New York

1980 Marisa del Re Gallery, New York

1984 Galleria Oro del Tempo, Rome

1984 Galleria Oro del Tempo, Rome

1985 H Ostium, Cagliari

1985 H Ostium, Cagliari

1986 La Soglia, Venice

1986 La Soglia, Venice

[ hide dÚpliants ]

"Why do I make collages?"

"Why do I make collages?"

(Esmeralda Ruspoli, 1982)

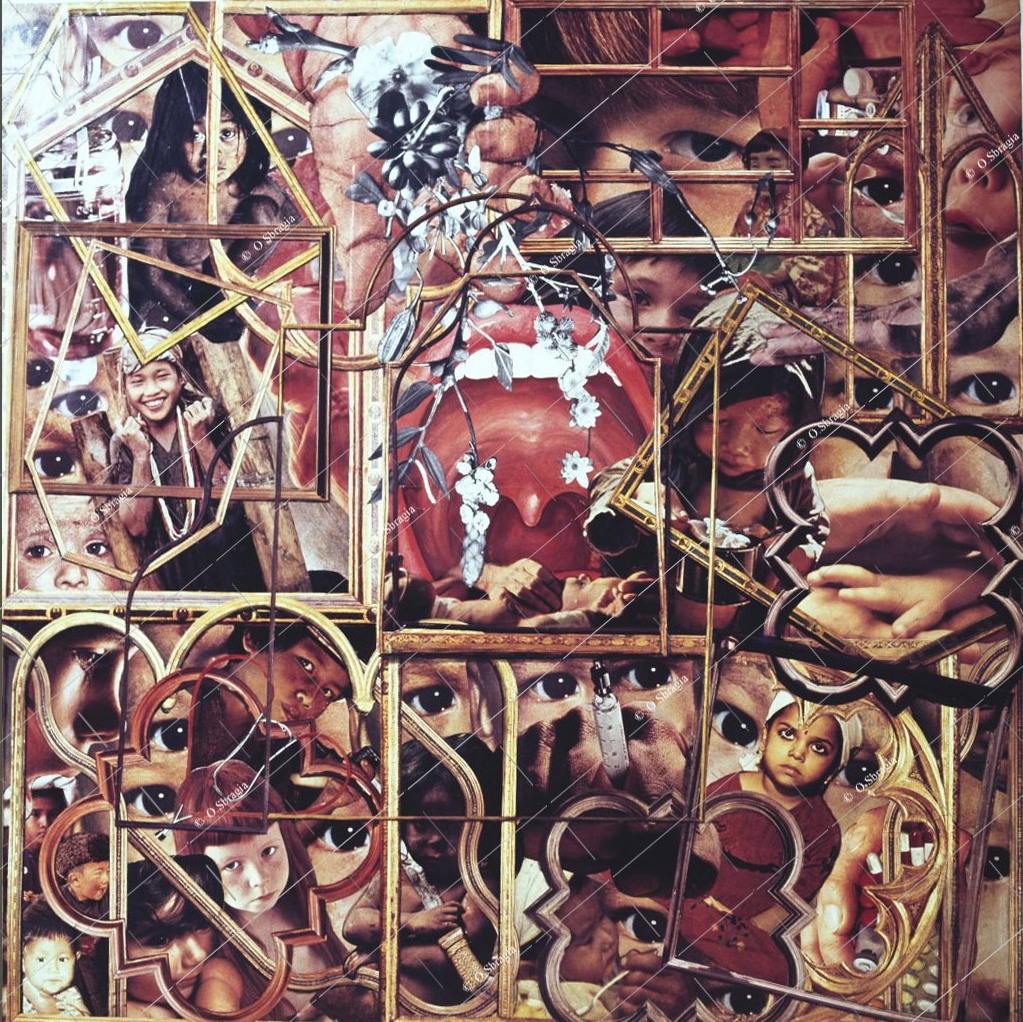

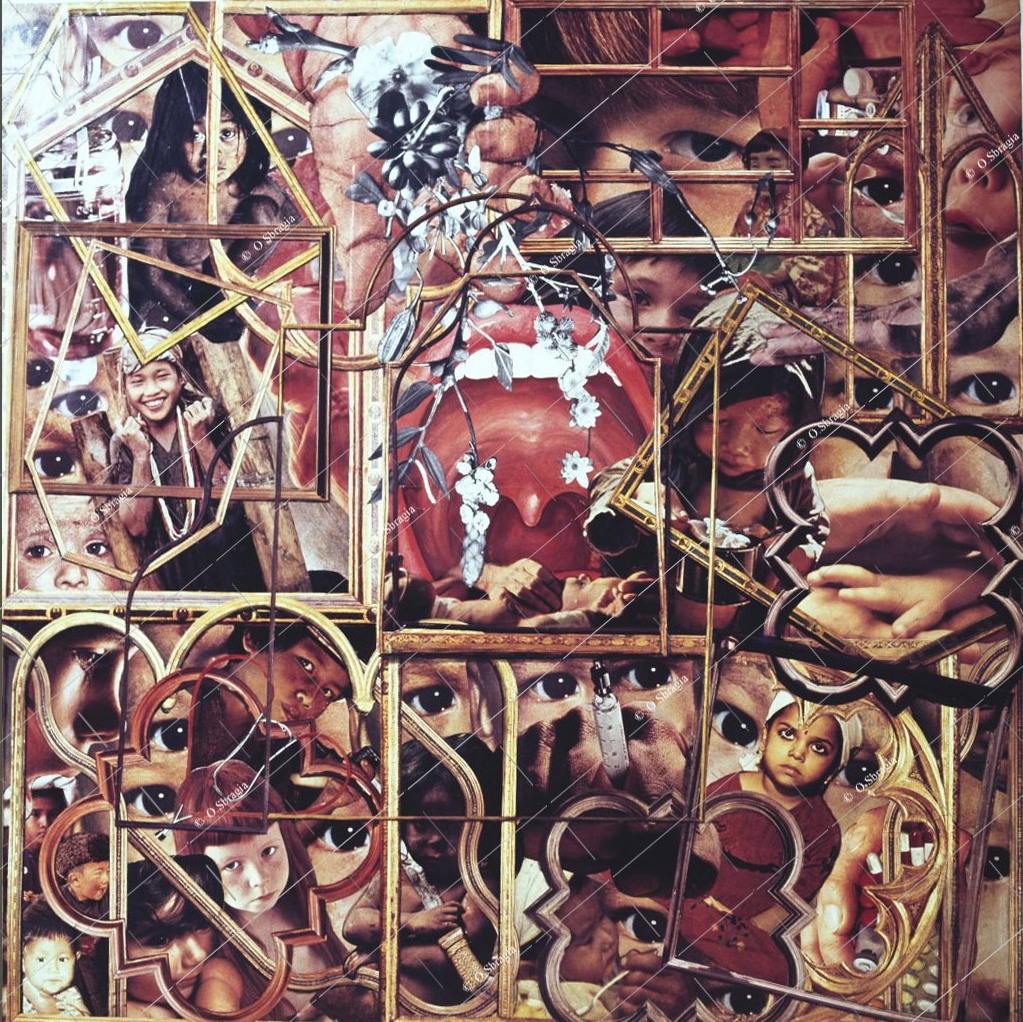

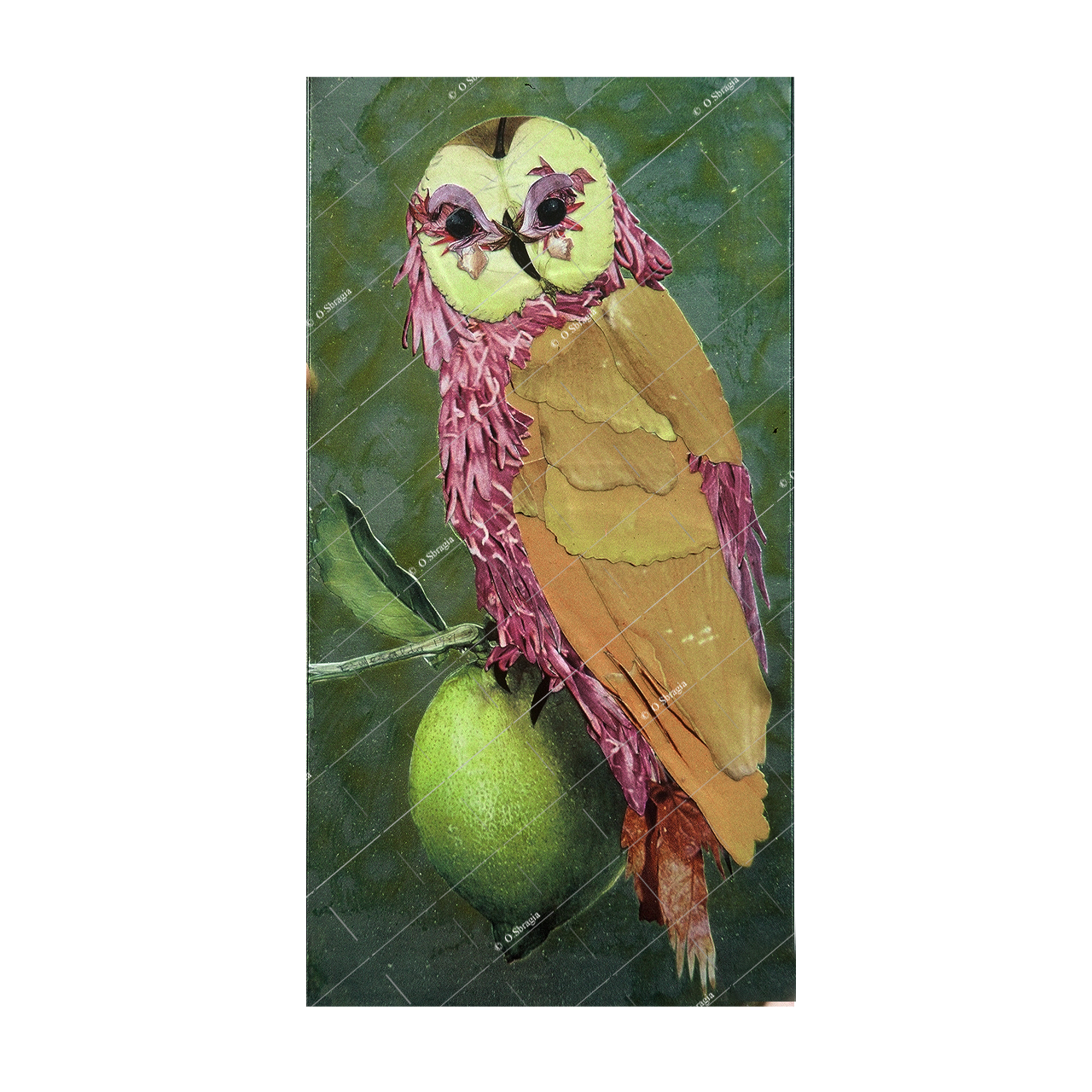

Children are always fascinated by scissors and by the magical falling of bits of paper which they cut without thinking.

Lonely children often insist upon attention, and grown-ups,

not always patient, find scissors and paper to be a good and harmless way of keeping them quiet I was a shy child: adults always seemed aggressive, and other children small copies of adults.

So, for me, happiness was found in solitude: in a corner in the garden of Maser, contemplating the palm trees moving softly in the air and the birds flying high in the Sky on the patio, watching

the bats that nested on top of the columns or the jekos hunting nightflies on the wall on the large terrace in Rome, peeping at the bees in the climbing roses or gazing at the swallows shrieking

as they passed. It was to be found in Farfa, an ancient abbey near Rome, hidden in the undergrowth observing the life of a country mouse, or down near the brook with nothing around but grass, olive trees,

pebbles, my dog, cat and monkey. The fairies showed me enchanted castles in a drop of water, the elves led me through a hole in an old tree stump to underground gardens where flowers walked around and chattered.

I soon found out how to cut around images and put them together so as to pin down my fantasies. It was a marvelous way of concretising the fleeting images that were awakening in me. This is how it

all began: cutting out my dreams.

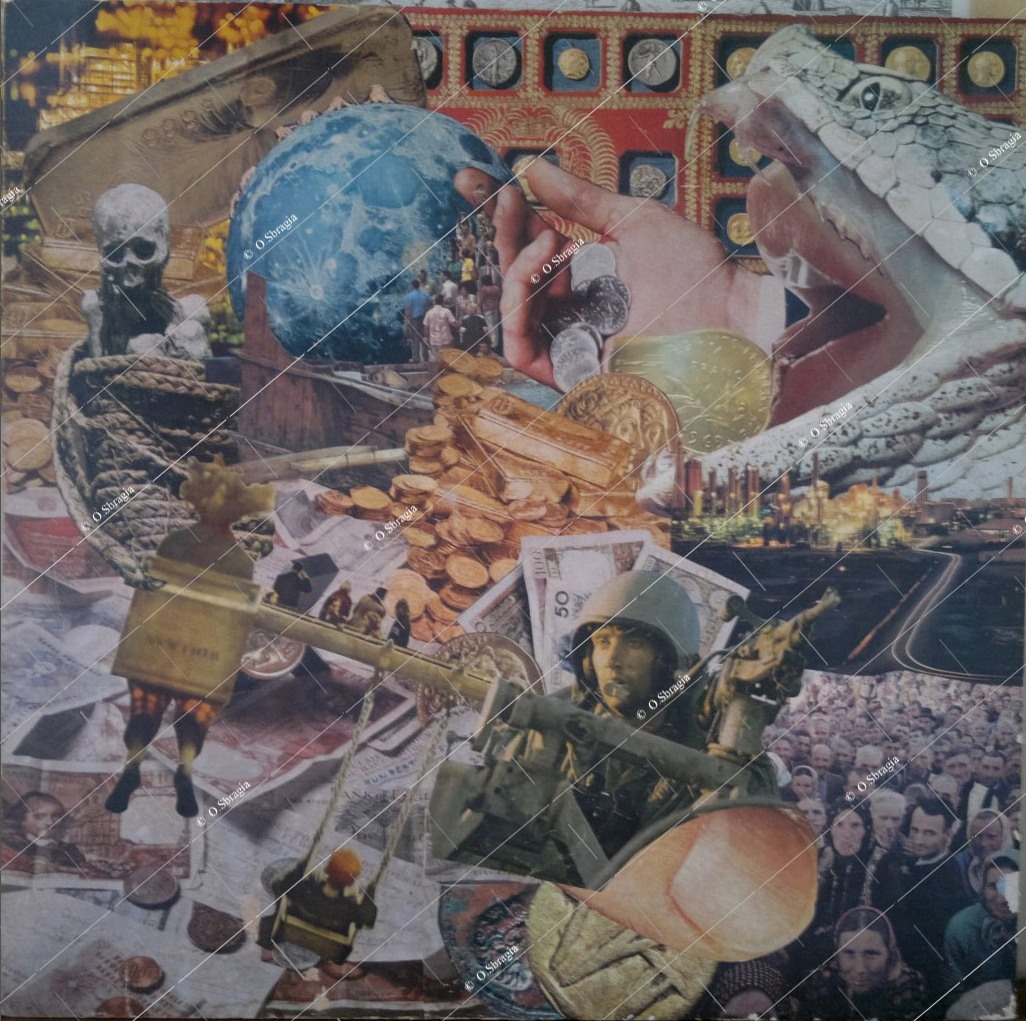

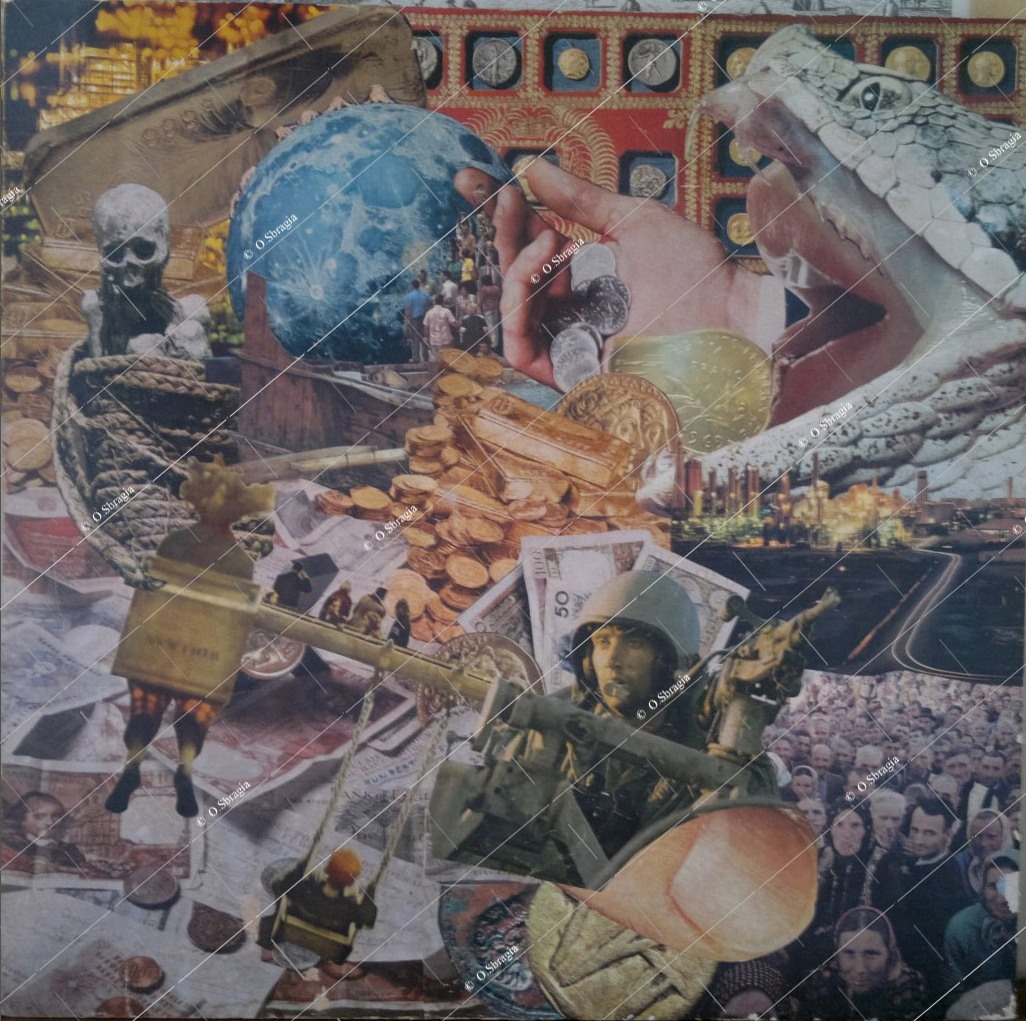

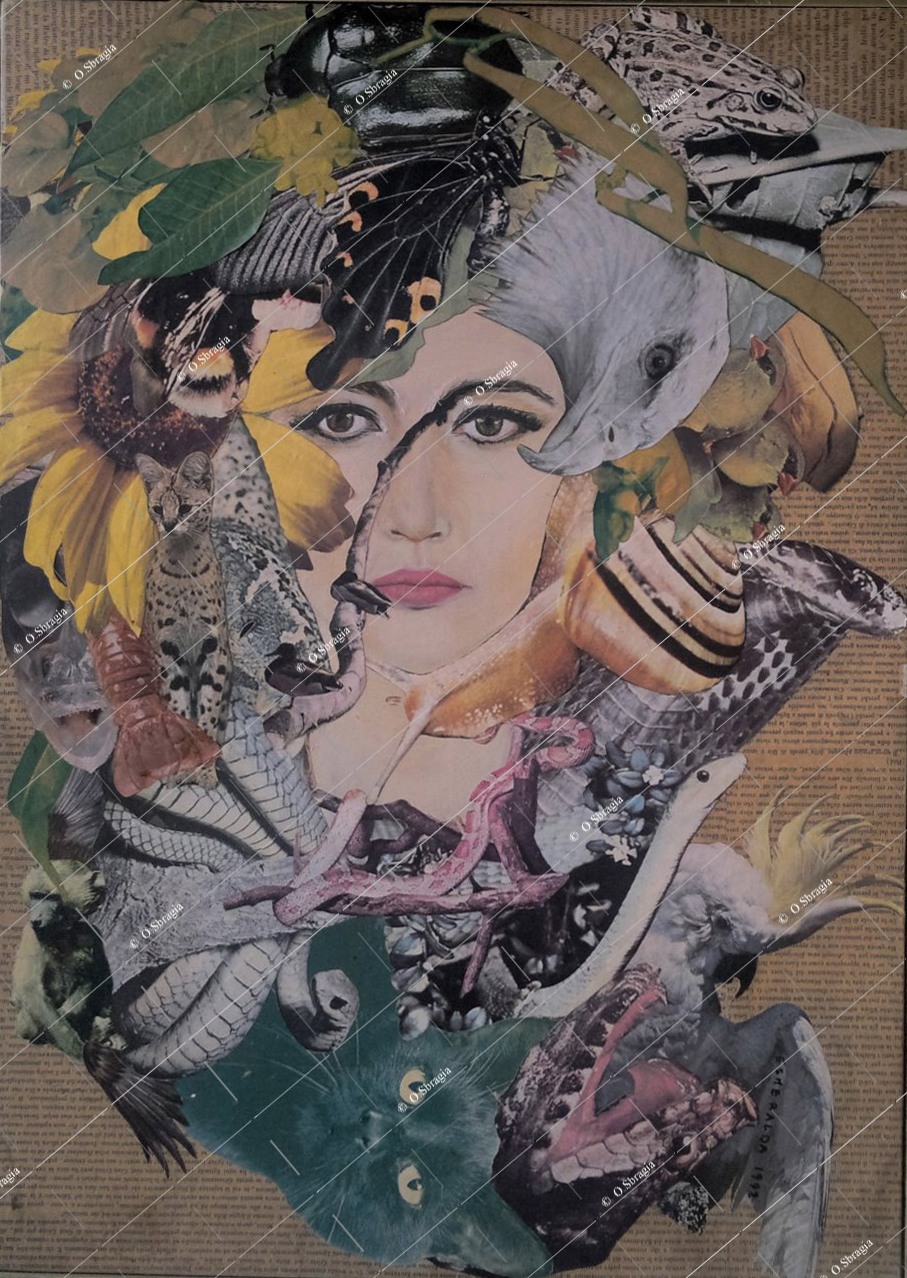

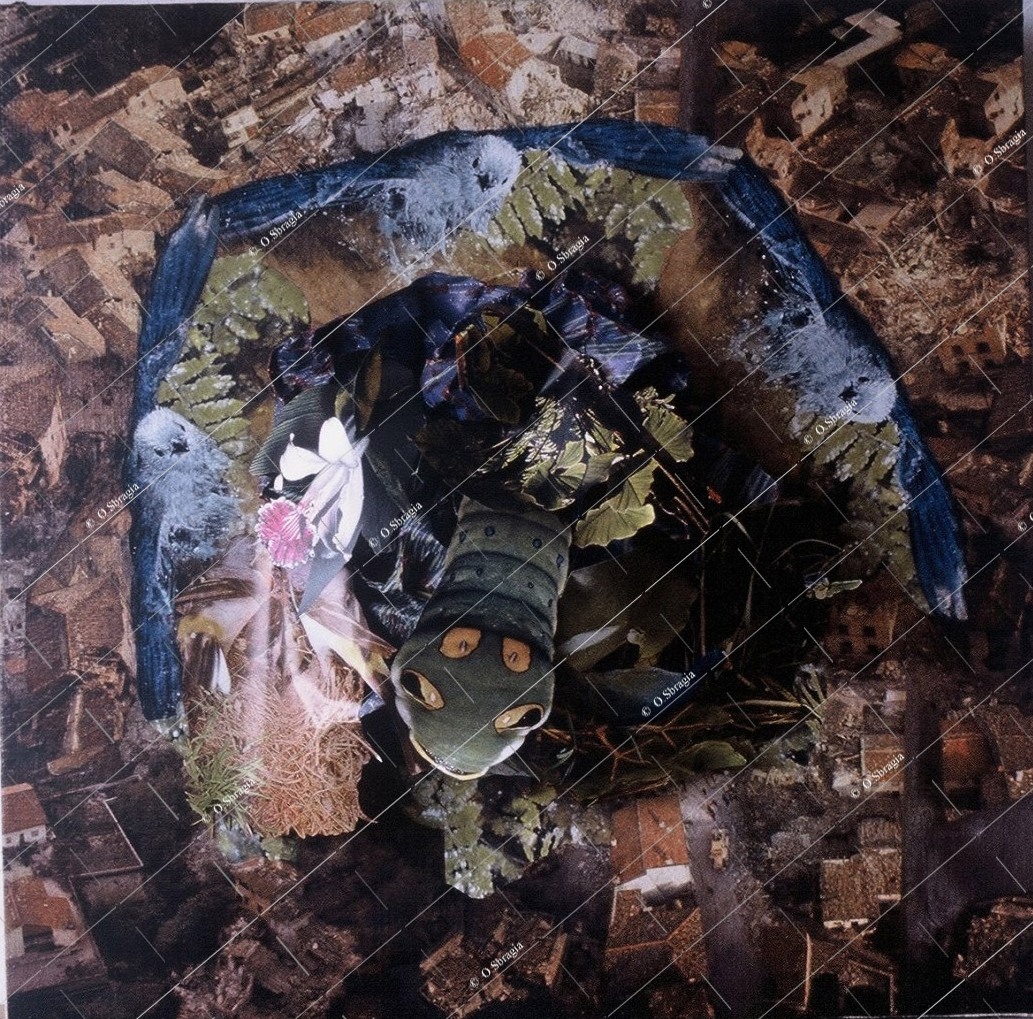

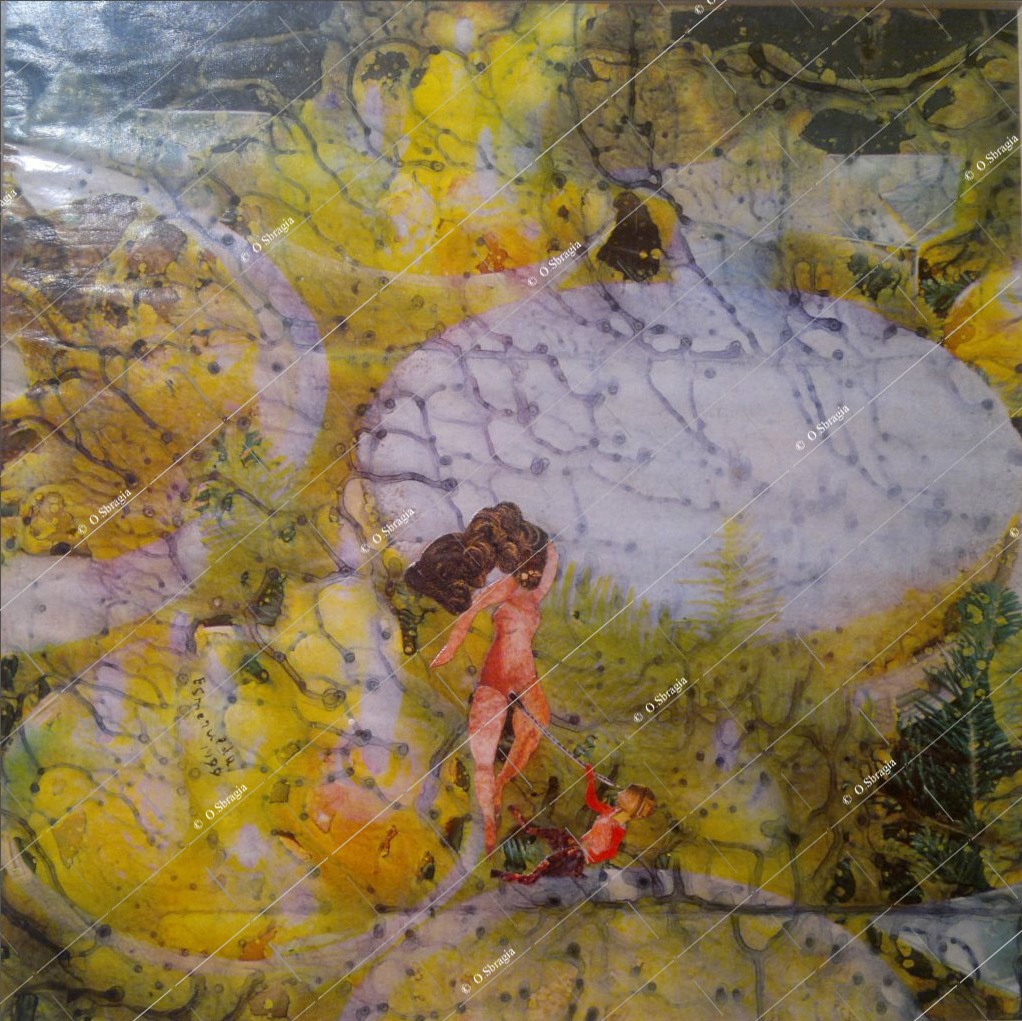

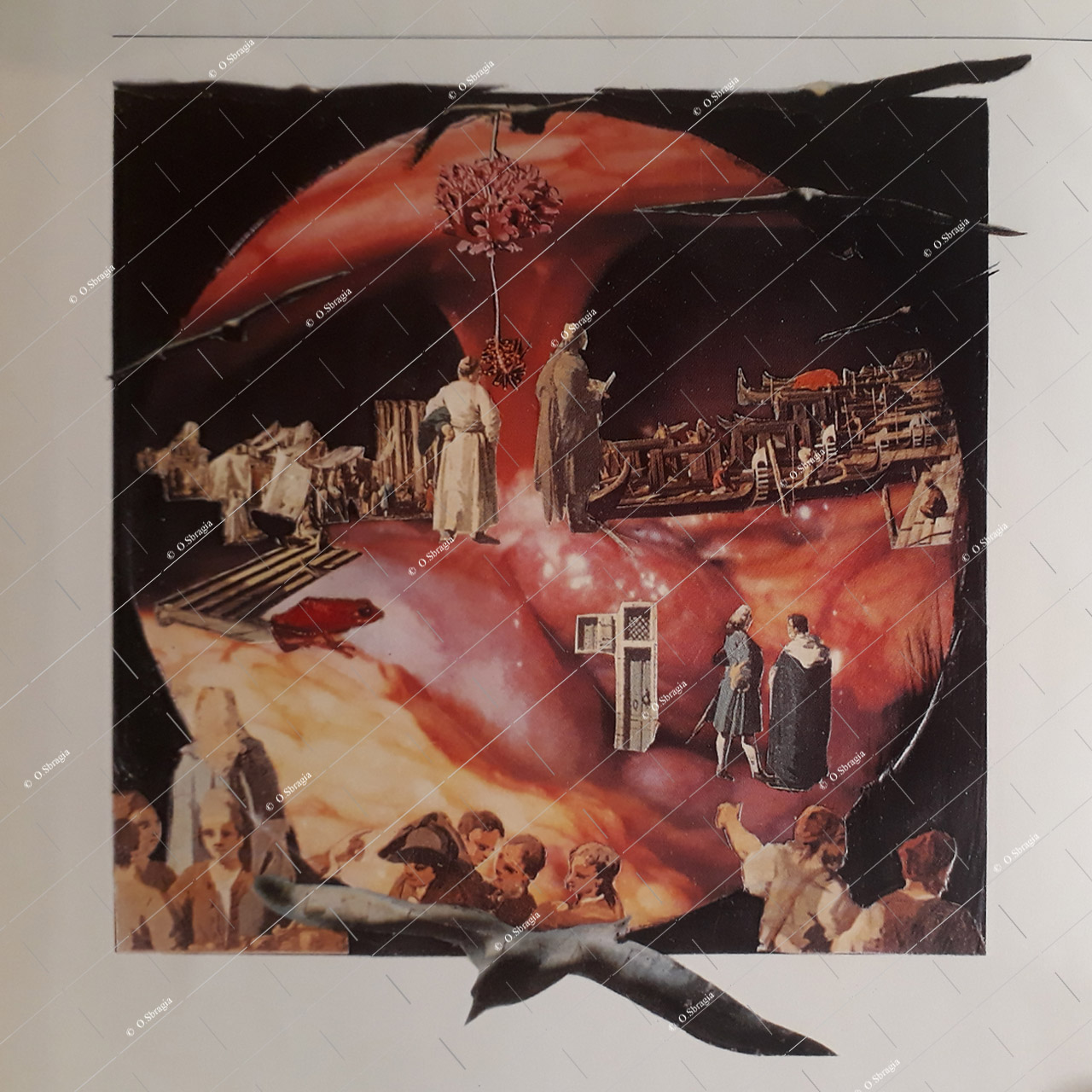

"The physical reality is that my body exists only in relation to this universe and in fact I am as attached to it and dependent on it as a leaf on a tree.

The universe is a unity my body and the world form a single process." (A. Watts).

As a baby in my pram, under a tunnel of hornbeam, this was absolutely clear to me as my eyes learned to see the sky through the branches above.

As I grew to be a child it became less clear but, when looking at a beetle on a stalk, an ant carrying something so much bigger than itself, or a butterfly or a bee going from one flower to another, I was fulfilled.

Later, as an adult woman, daily life took the place of everything, and I forgot completely my relation to the universe. When this became clear to me, I began to consider collages as serious work.

I was learning to glue

my dreams together with a certain order, to contain them in comprehensible constructions. Sometimes I knew exactly what it was I wanted to create, although I never knew with which images I would fulfil my ideas.

At other times, everything began with the casual finding of an image which would break loose that magic chain of selections whereby pieces seemed to group together by themselves.

My urgent need to glue together

pieces of paper had no real purpose - it just came out like a photograph from a Polaroid camera.

It was what was inside of me, but I was uncertain as to what I was trying to say. People often found it frightening,

but for me this process was always a happy one.

Then, in Sicily, I spent a whole night watching the opening and dying of a cactus flower. When the cicadas stopped singing and the world was completely motionless,

waiting for the day to take the place of night, the petals began to open. The crickets exploded. A light perfume wafted in the air as the green enclosure opened, displaying an enormous number of thin white petals

similar to the light feathers on the head of a crowned crane, and these petals swayed light a sea anemone. The full moon rose as red as a watermelon, slowly lighting the sky as bright as a floodlight. Hundreds of small

flying insects with transparent wings arrived out of nowhere and began entering the flower that by now vibrated very visibly. The perfume was stunning, and the beauty unutterable. By the time the first bird sang at dawn,

all life had disappeared and only a sad yellowish bunch of flopping petals dangled.

I had lived through it all unconscious of myself.

The flower and I were the same thing - my body and the world had formed a single processo.

This is the exciting revelation I want to put in my collages.

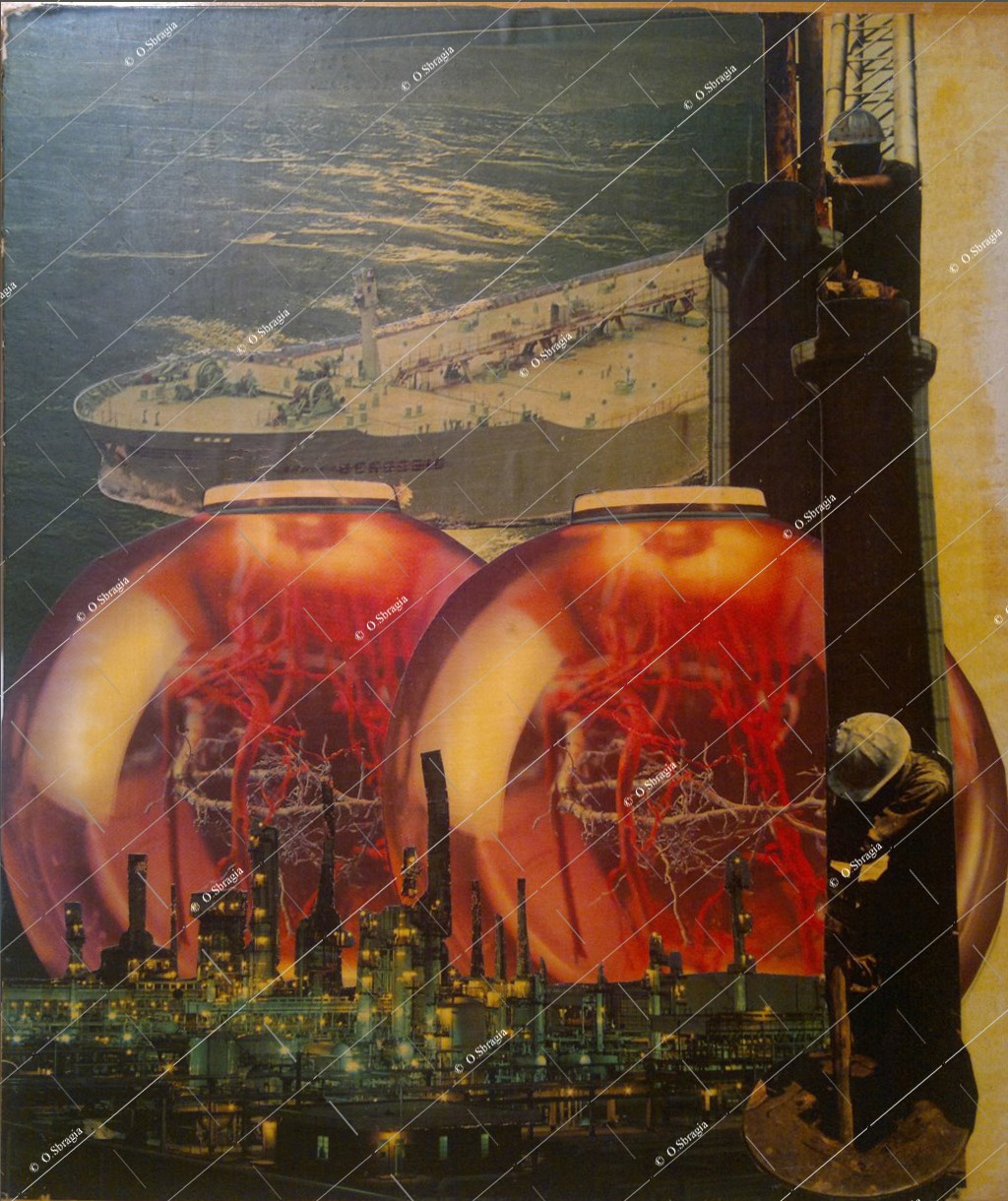

The happy amazement I feel in knowing that the linking together of everything is a marvellously tidy chaos, where images express themselves violently but are at the

same time sweet the sweetness consisting for me in the marvel of belonging to this "knowledge/mystery" that renews itself continually. Everything I see and touch has been something else, will in due time become something else

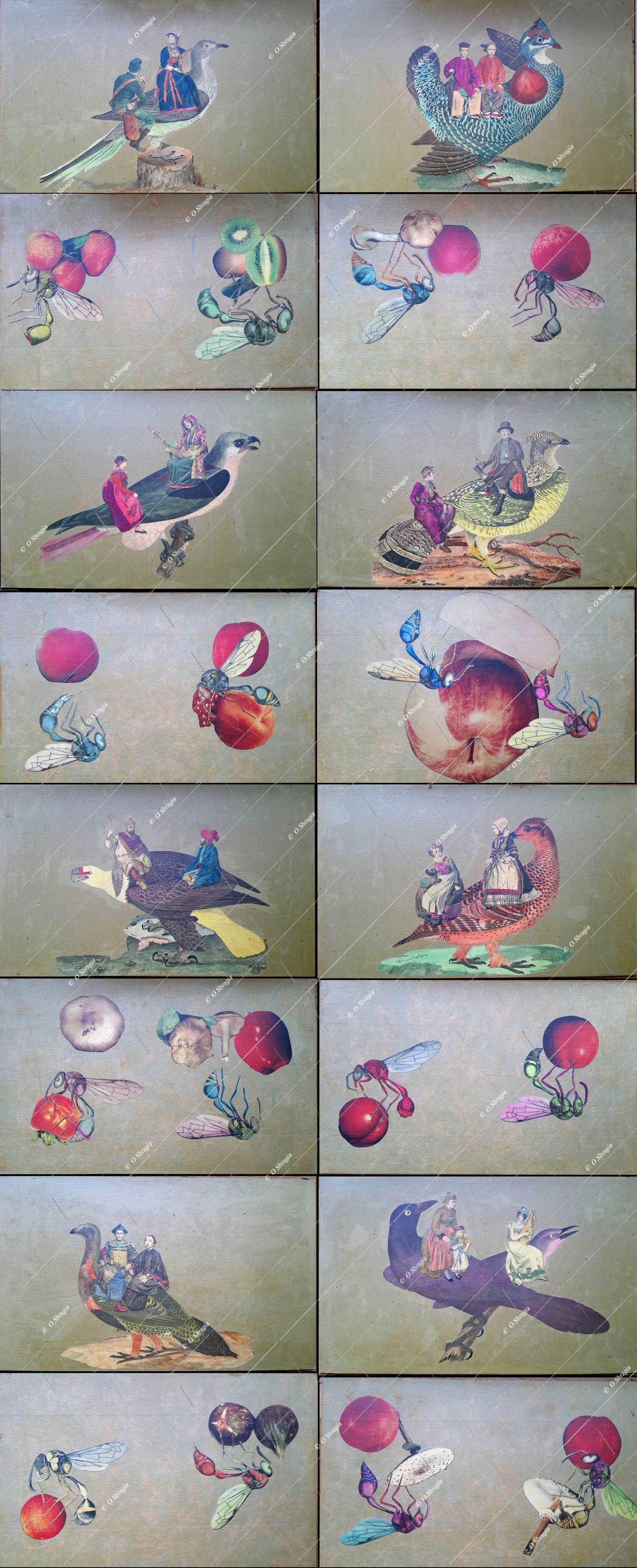

-so why not a duck of seaweed, a mountain of people, a bird of tuna fish and soldiers? That is why I glue my sensations in a happy confusion, very elaborately put together so as to appear to be a defined figure hiding in its

heterogeneous essence- picking the images that are bombarded on us incessantly, especially photographs, that explore every existing thing, from a dying soldier to the egg of a flea.

Why do I work with pre-existing images instead

of painting them myself?

Images that arrive on me unlooked-for originate something completely different from what they represent bringing forth series of new fantasies that no imagination, however wild, could ever put together by itself.

I painted or drew my images, I would only be putting down my fantasies, whereas when I take images for what they are and alter them so as to make them become something else, it brings them to mean innumerable things and to be other than they seem.

What I mean, said in rather a blunt way, is this: everything is everything.

Critiques

Critiques

SainJust

NovitÓ - Rivista di Decorazione, June 1955

An Invitation to Fantasy

[read the article]

[hide the article]

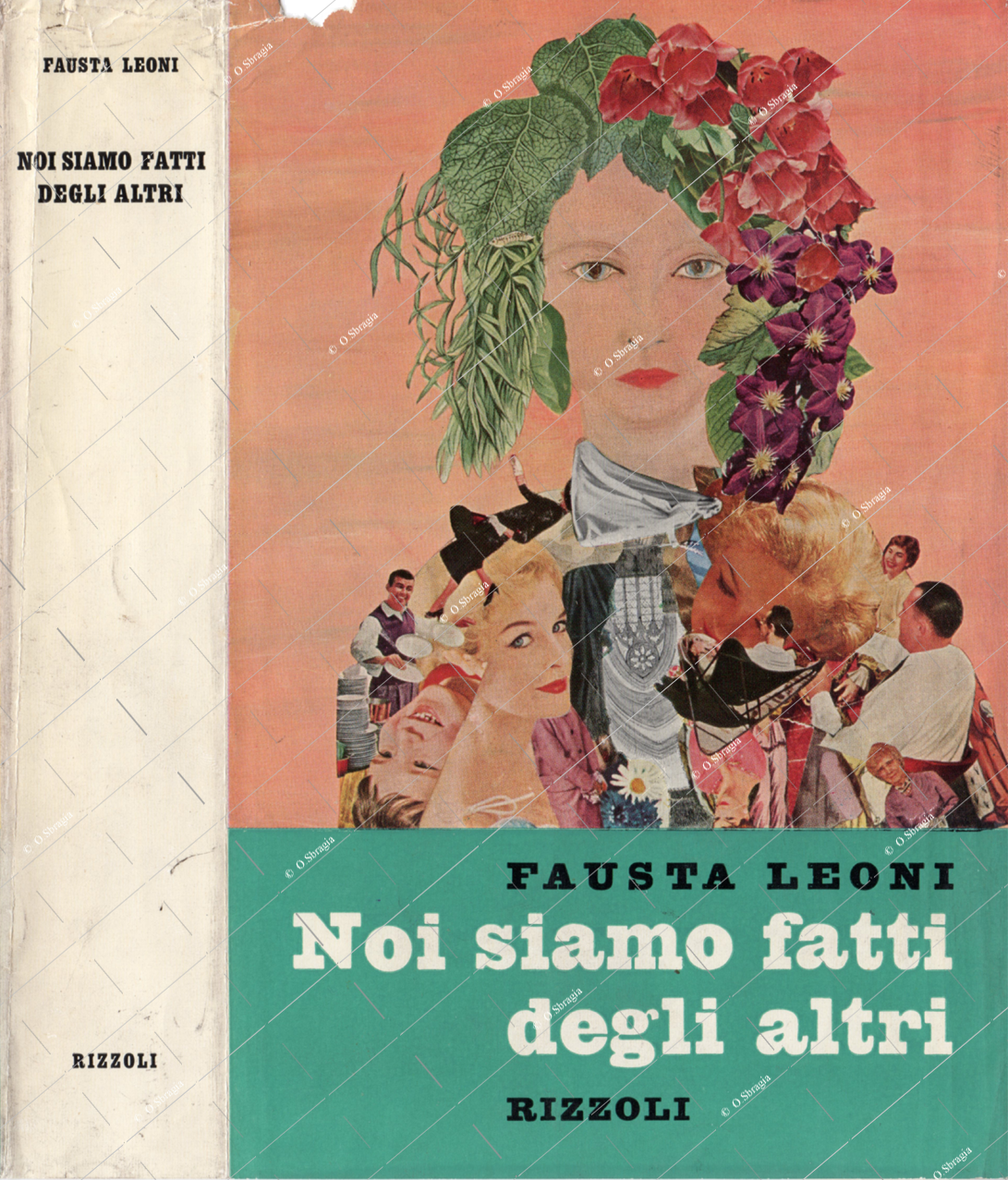

That collage, like all other fashions that have been popular, is subject to fantasy is not something new. It might

even be said that this fashion is one that is constantly born a new since it is bound to the personality of its creator.

Thus, it can be viewed each time with new eyes for it matters not if it is discovered in the pages of an album as

I recently found in a 'gallery of friendships' where every page dedicated to a person displays an imaginative montage

of photographs and clippings underlining aspirations and character with humour. Or whether, as in this case, the intent

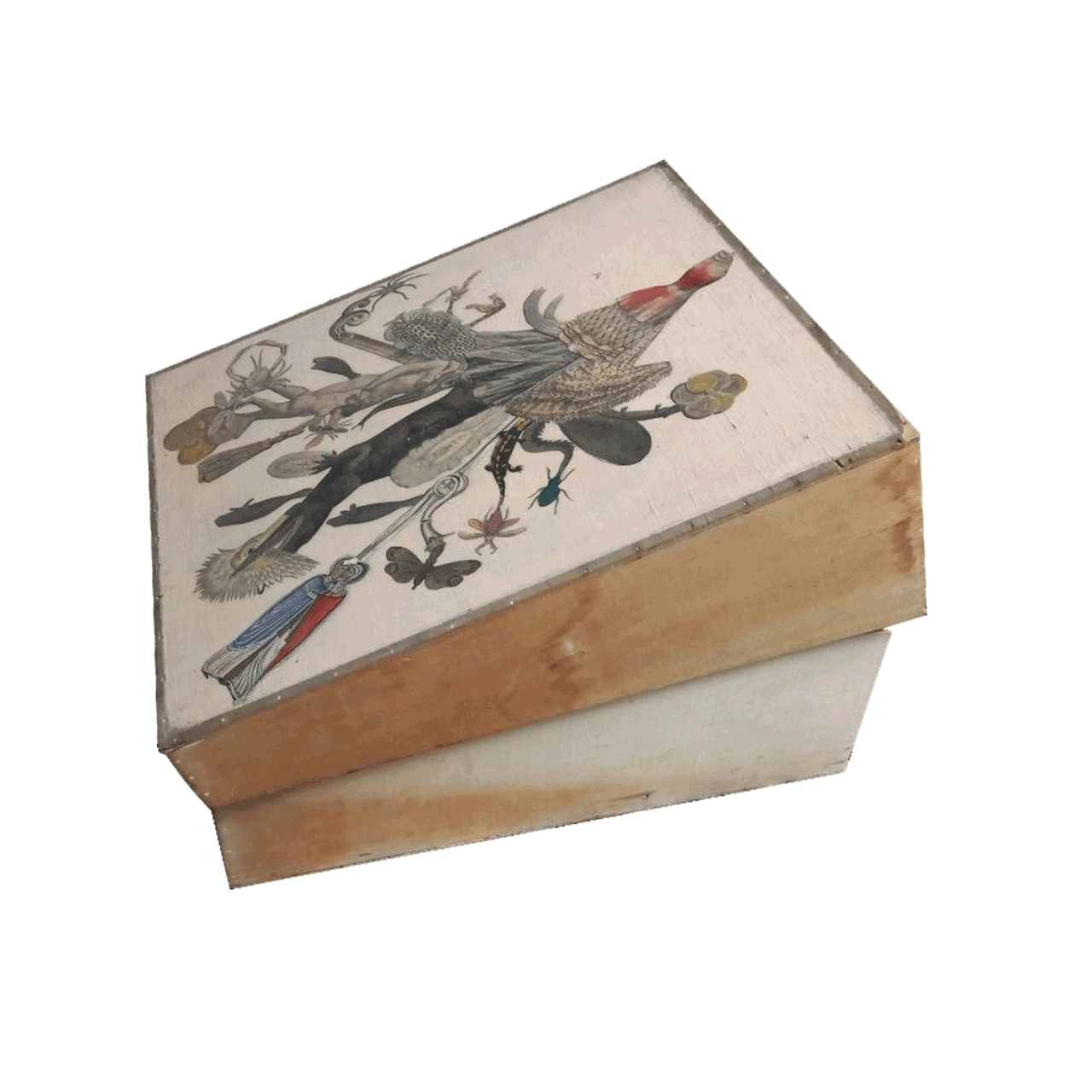

is to resolve some problem of interior decoration. Entire panels, doors or screens, even tables and trays and boxes are

periodically subject to this vogue and I believe that when someone endowed with fantasy tries to work with scissors and

paste then nothing is salvageable: books, prints, magazines, postcards, everything is lumped together. The pictures that

Titina De Filippo created with scissors instead of a paintbrush come to mind, as do the figures of shells cut from old

prints that TitinaRota, who lived at Capri and was surrounded by seascapes, composed into pictures of amusing surrealism.

But most of all I think of how Esmeralda spends her time: a cat on her knees, a baby in the cradle and another sitting

at her feet, surrounded by papers that her scissors devour recreating unexpected compositions. It must be a little like

watching the clouds pass by. The only difference being that these cut out images can then be arranged according to a whim

of the moment, therefore becoming the witnesses of a capricious fantasy: a dream that remains in reality.

[hide the article]

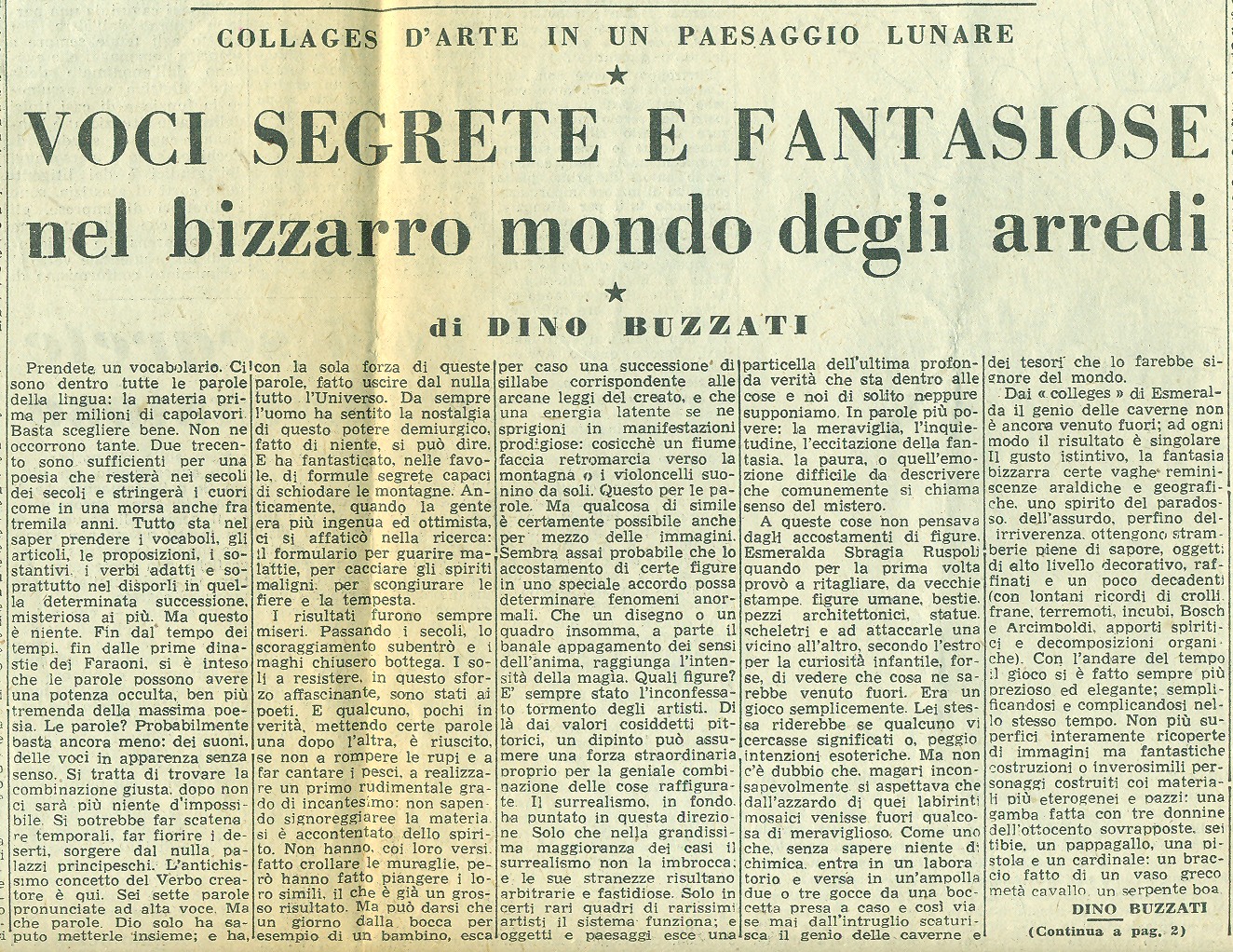

Dino Buzzati

La Fiera letteraria, 10 February 1957

Secret and Fantastic Voices In The Bizarre World Of Furnishings

[read the article]

[hide the article]

Pick up a dictionary. Inside are all the words of the language: the prime material for millions of works of art. One need only

choose well. Not many are needed. Two or three hundred suffice for a poem that will remain for centuries and centuries and continue

to break hearts even in three thousand years. It is only a matter of knowing how to take words, articles, prepositions, nouns and

verbs and arrange them in such a way that still remains mysterious to most of us. But this is nothing. From the time of times, since

the first dynasties of the Pharaohs, it was understood that words could have an occult power, much more tremendous than the greatest

poetry. Words? Probably even less: sounds, voices without meanings. It was a matter of finding the right combination, after that nothing

would be impossible. It would be possible to unleash rainstorms, make deserts flower, cause princely palaces to rise up from nothing.

The very ancient concept of the Word creator is here. Six or seven words pronounced aloud. But what words. Only God knew how to put them

together; and with the force of these words he made the entire Universe emerge from nothing. Man has always felt nostalgia for this

demiurgic power, made of nothing one could say. And he has fantasized in tales about secret formulas capable of unlocking mountains.

In ancient times, when people were more ingenuous and optimistic, they laboured in their research: the formula for healing illness,

for expelling malign spirits, for warding off wild beasts and storms.

The results were always poor. With the passing of centuries, discouragement took over and the magicians closed their shops. The only

ones who continued to resist in this fascinating effort were the Poets. And some, in truth, only a few, by lining up certain words one

after another, did manage, while not to break rocks and make fish sing, to produce a first rudimentary degree of enchantment: not knowing

how to master the material, they were content with the spirit. They could not bring down walls with their verses, however, they did make

their fellow creatures weep, and this already was a great result. But it may be that one day out of the mouth of a child, for example,

there may come a succession of syllables corresponding to the arcane laws of creation, and that a latent energy will be released in prodigious

manifestations; so that a river reverses its flow and moves up the mountain or cellos play on their own. This, as far as words are concerned.

But something similar is also certainly possible by means of images. It seems quite probable that the placement of certain figures side by

side might determine abnormal phenomena: that a drawing or a painting, apart from the banal satisfaction of the senses of the soul, might

reach a magical intensity. What figures? This has always been the secret torment of artists. Apart from so-called pictorial values, a painting

might assume an extraordinary force given the ingenious combination of the objects depicted. Surrealism has, basically, aimed in this direction.

Except in the vast majority of cases, surrealism does not succeed and its eccentricities may appear arbitrary and fastidious. Only in certain rare

paintings of some very rare artists does the system work; and from the association of figures, objects and landscapes a particle emerges of the

ultimate profound truth lying within things that we cannot even imagine. In simpler terms: the wonder, anxiety, excitement of fantasy, the fear

or that emotion which is difficult to describe, commonly referred to as a sense of mystery.

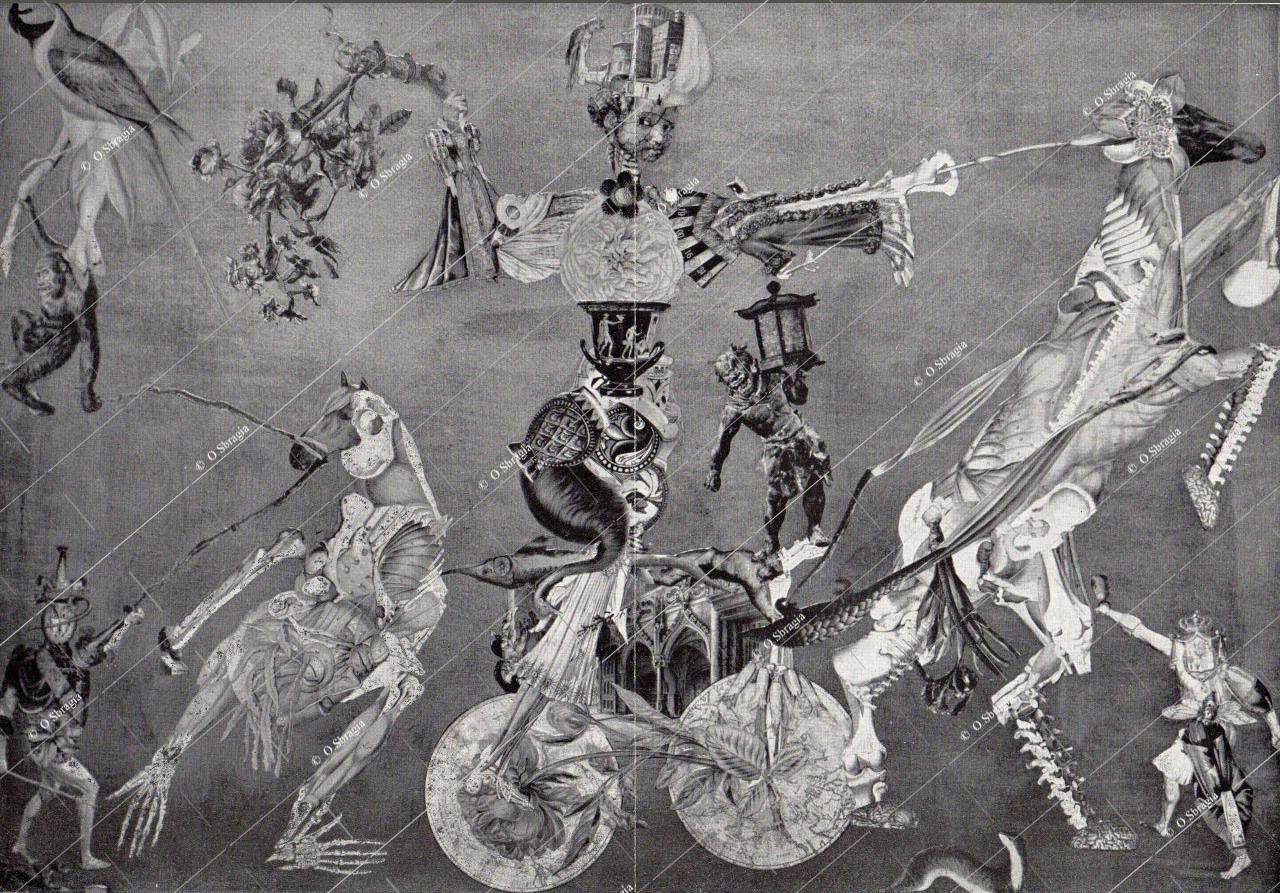

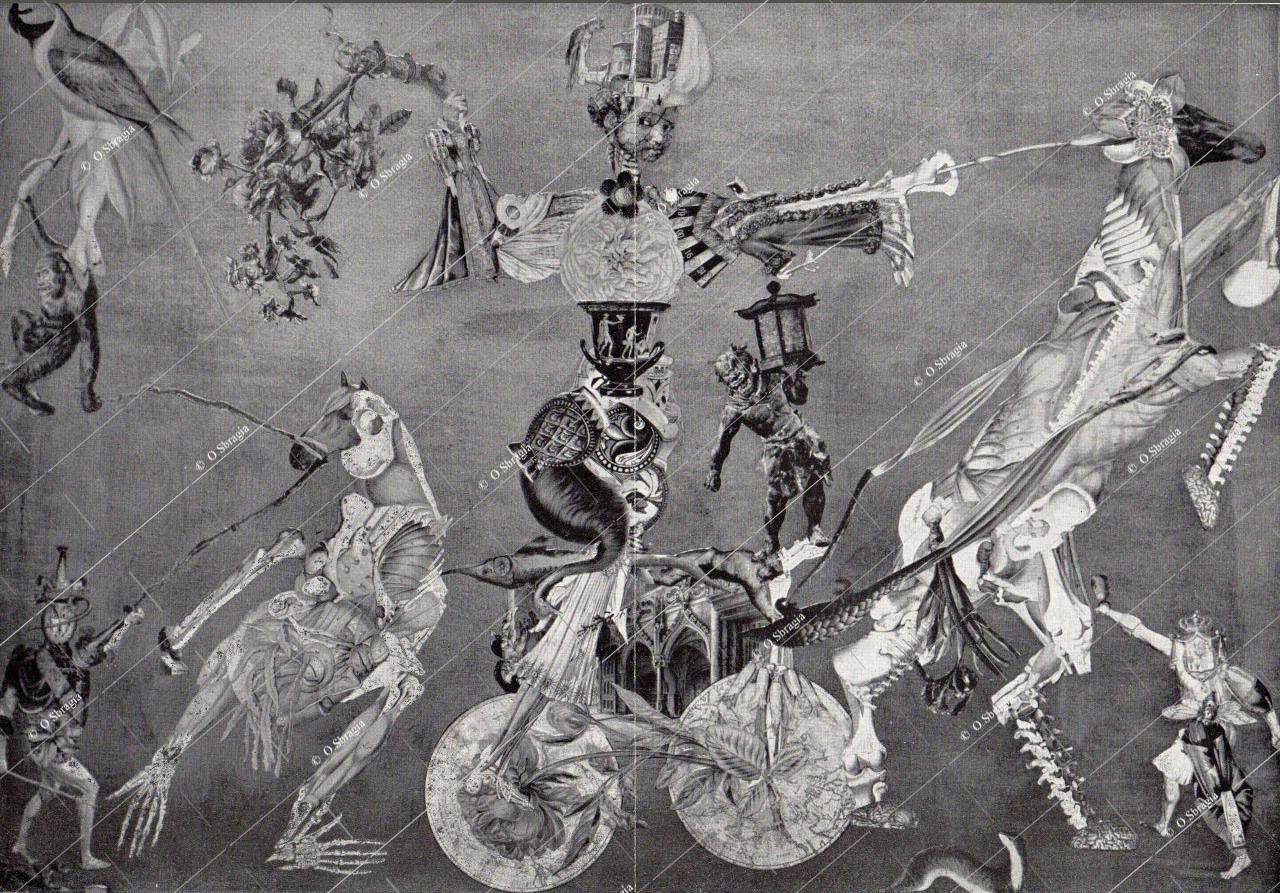

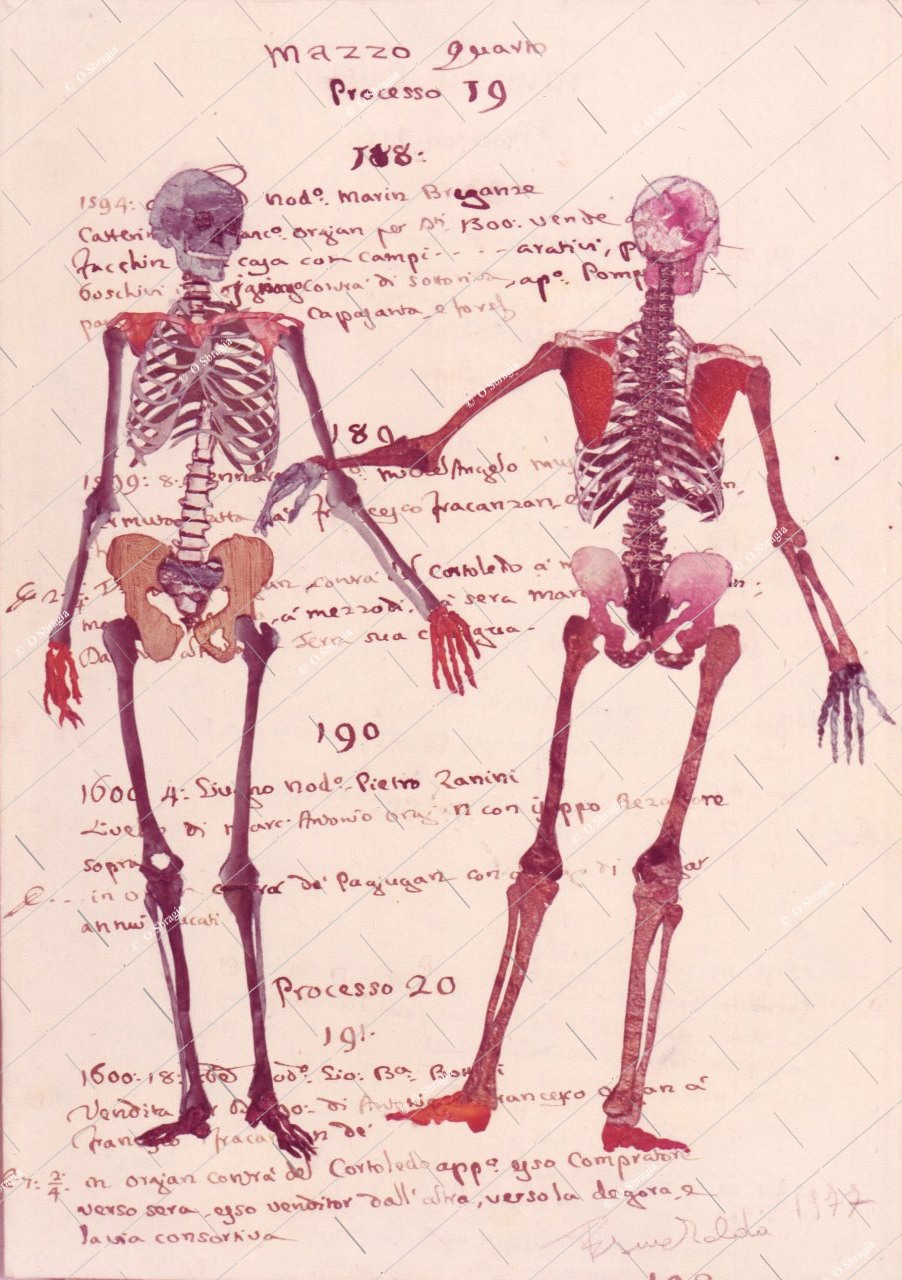

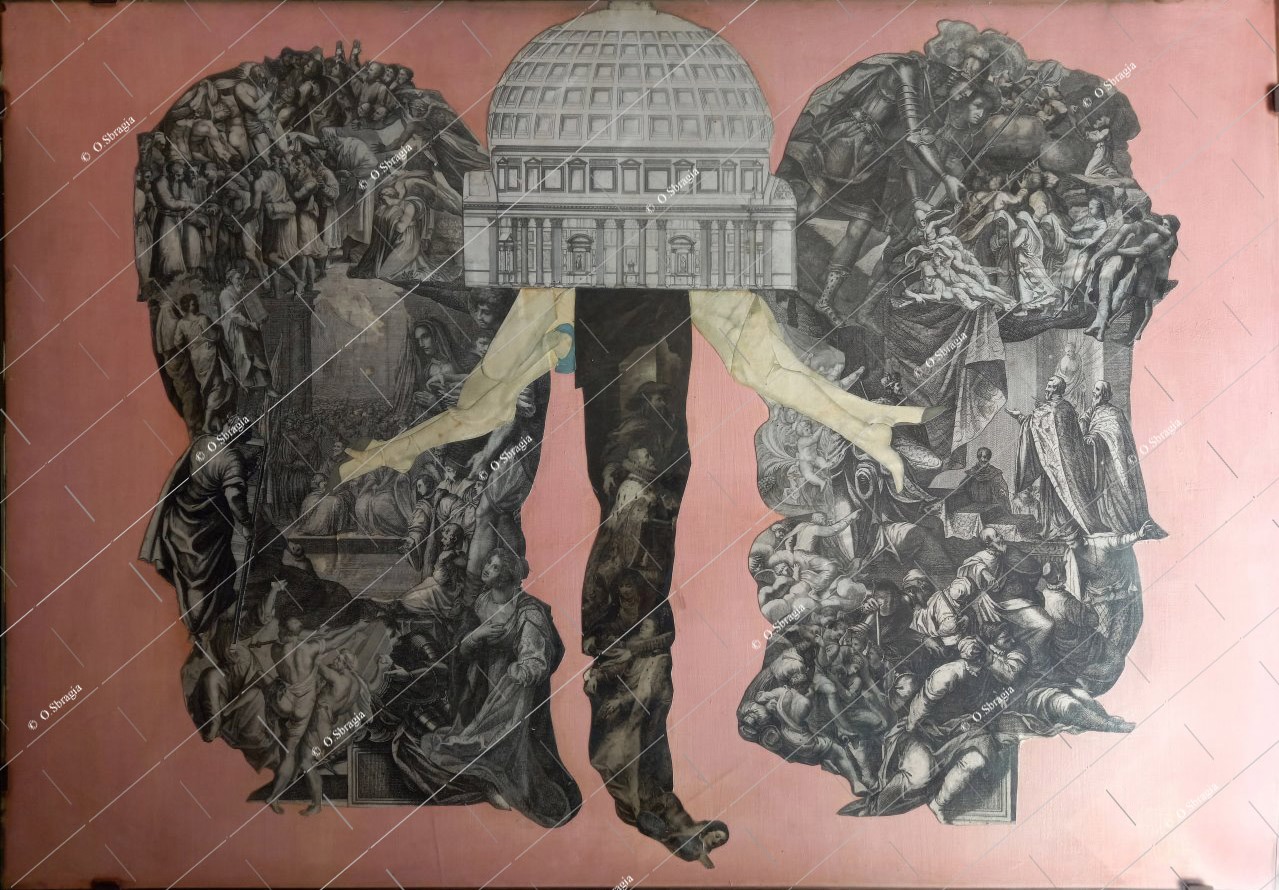

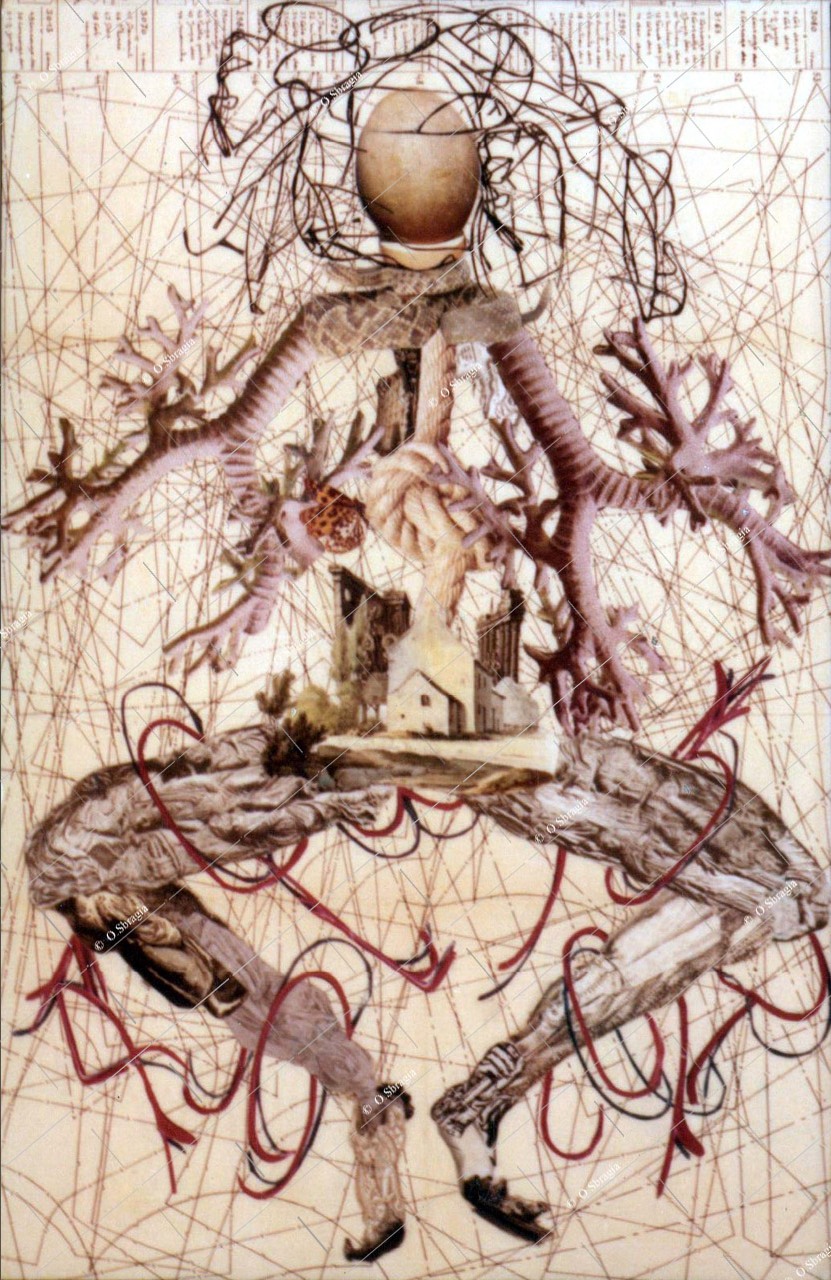

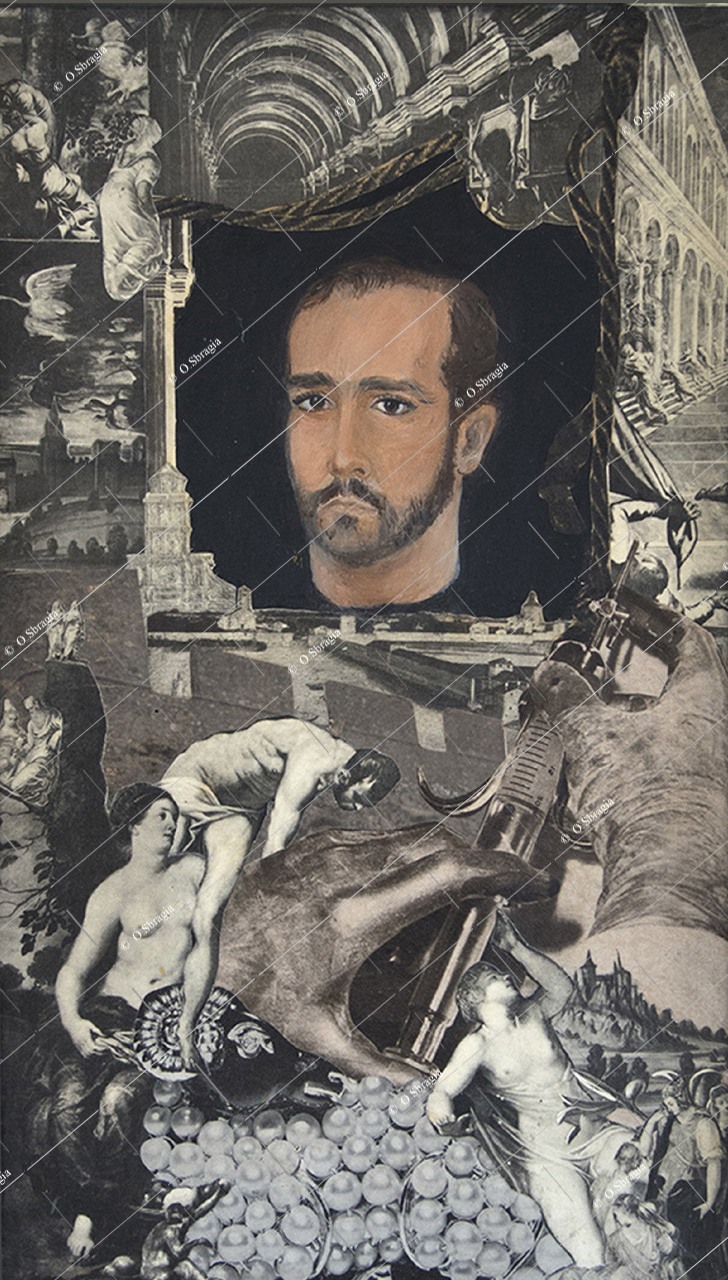

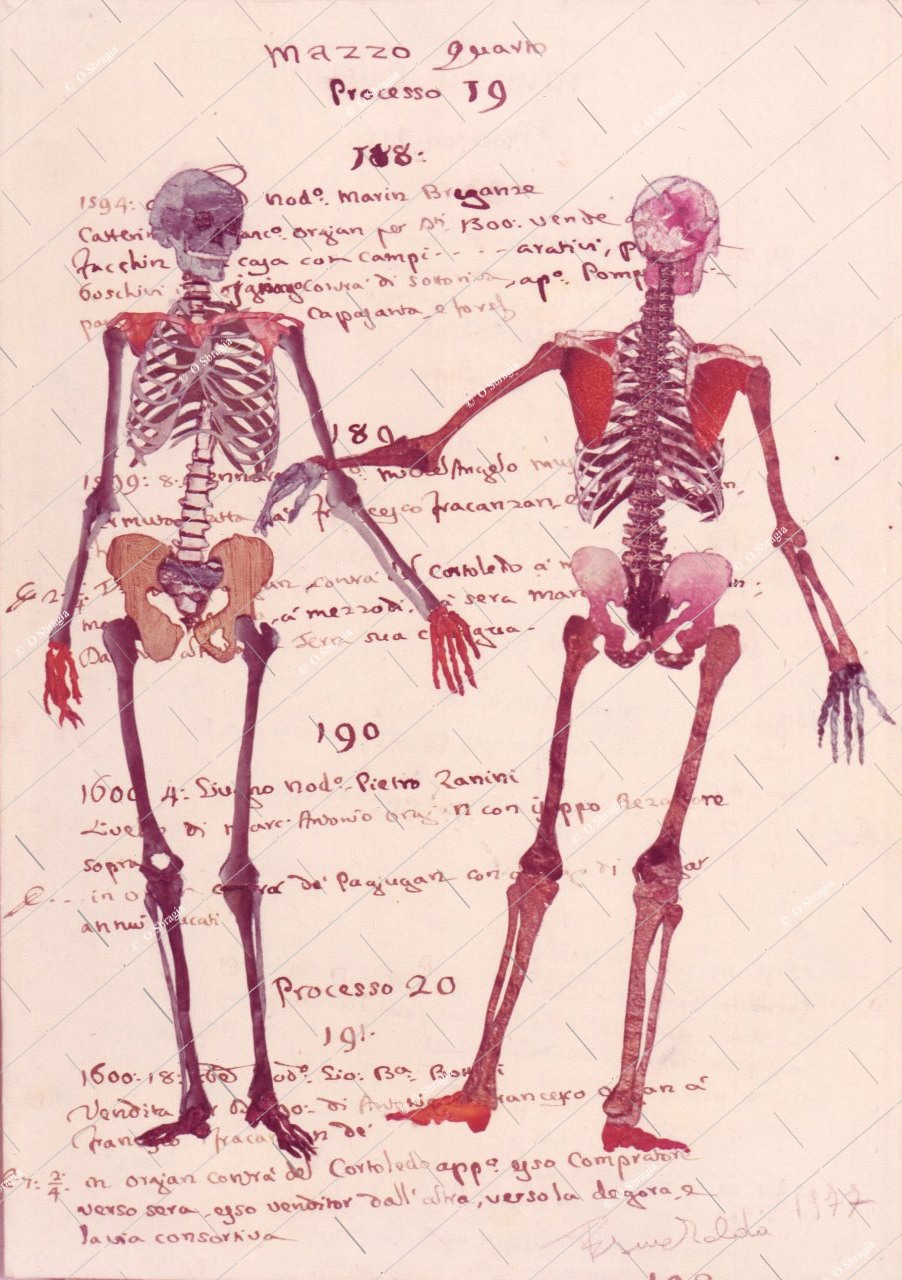

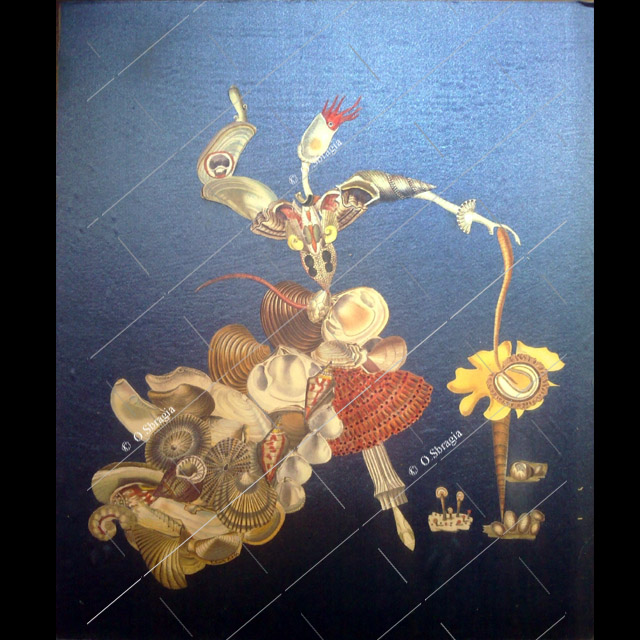

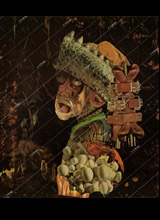

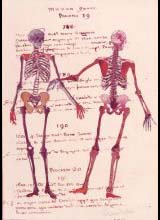

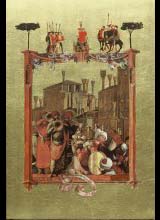

Esmeralda Sbragia Ruspoli was not thinking about this association of figures the first time she cut out human bodies, beasts, architectural

pieces, statues and skeletons from old prints and placed them alongside one another, much like a child might do to see what it would look like.

It was simply a game. She herself would laugh were anyone to try to find any significance or, even worse, esoteric intentions. But there is no

doubt that, perhaps unconsciously, she expected that out of the daring of those mosaic labyrinths something marvellous might come forth. As when one,

without knowing anything about chemistry, enters a laboratory and pours two or three drops into an ampoule from a bottle picked up by chance and out

of this concoction appears a genie and treasures that could make him master of the world.

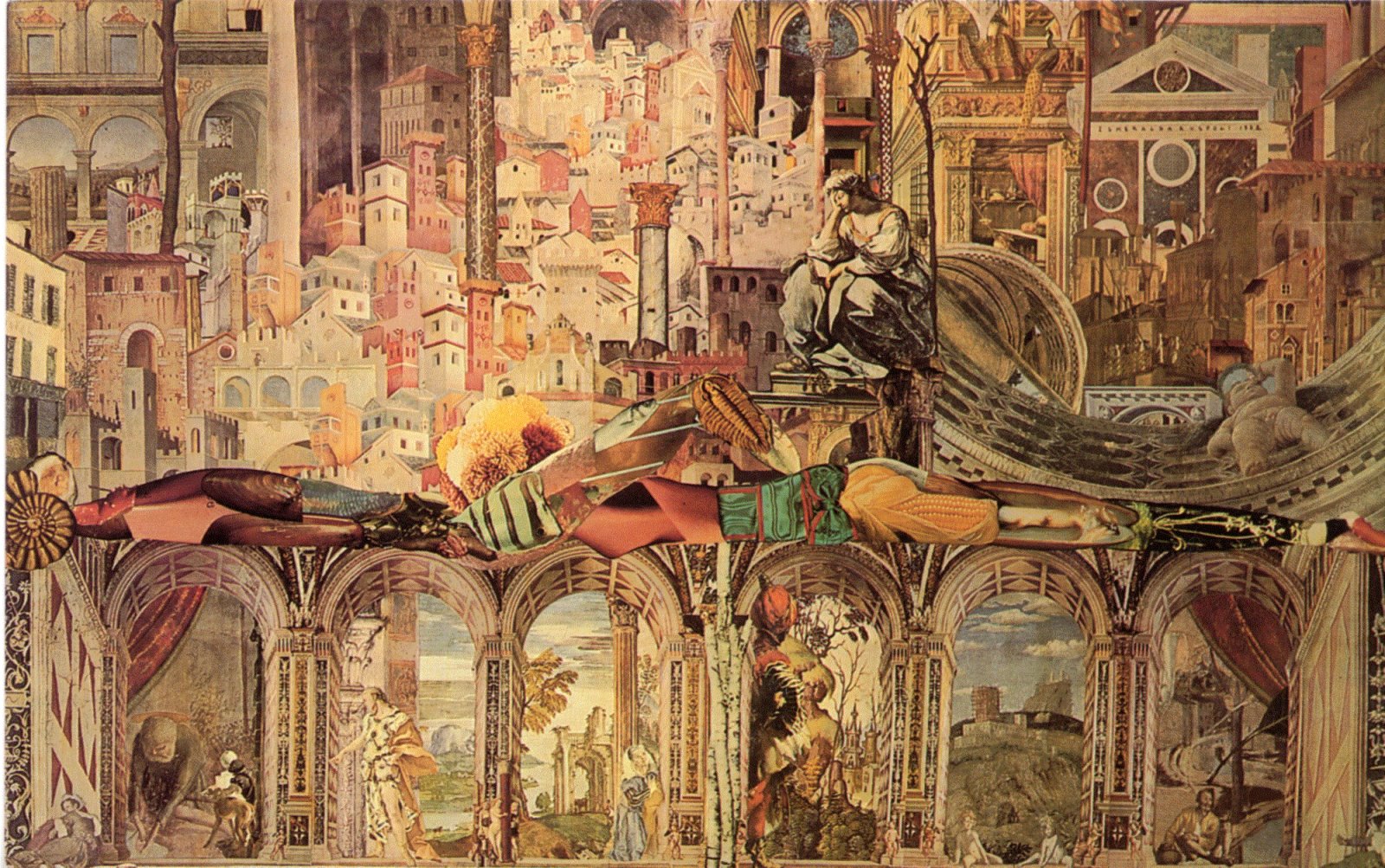

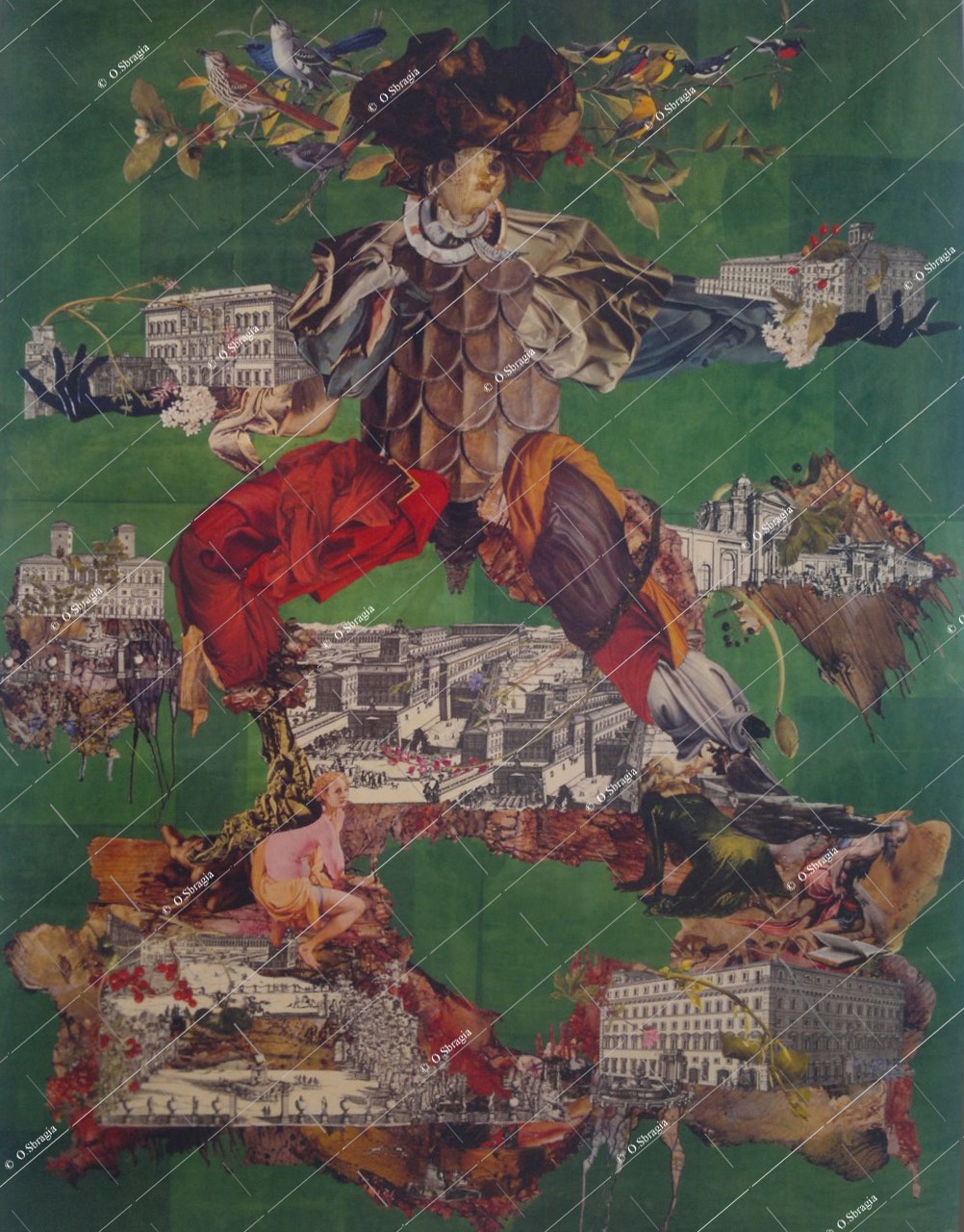

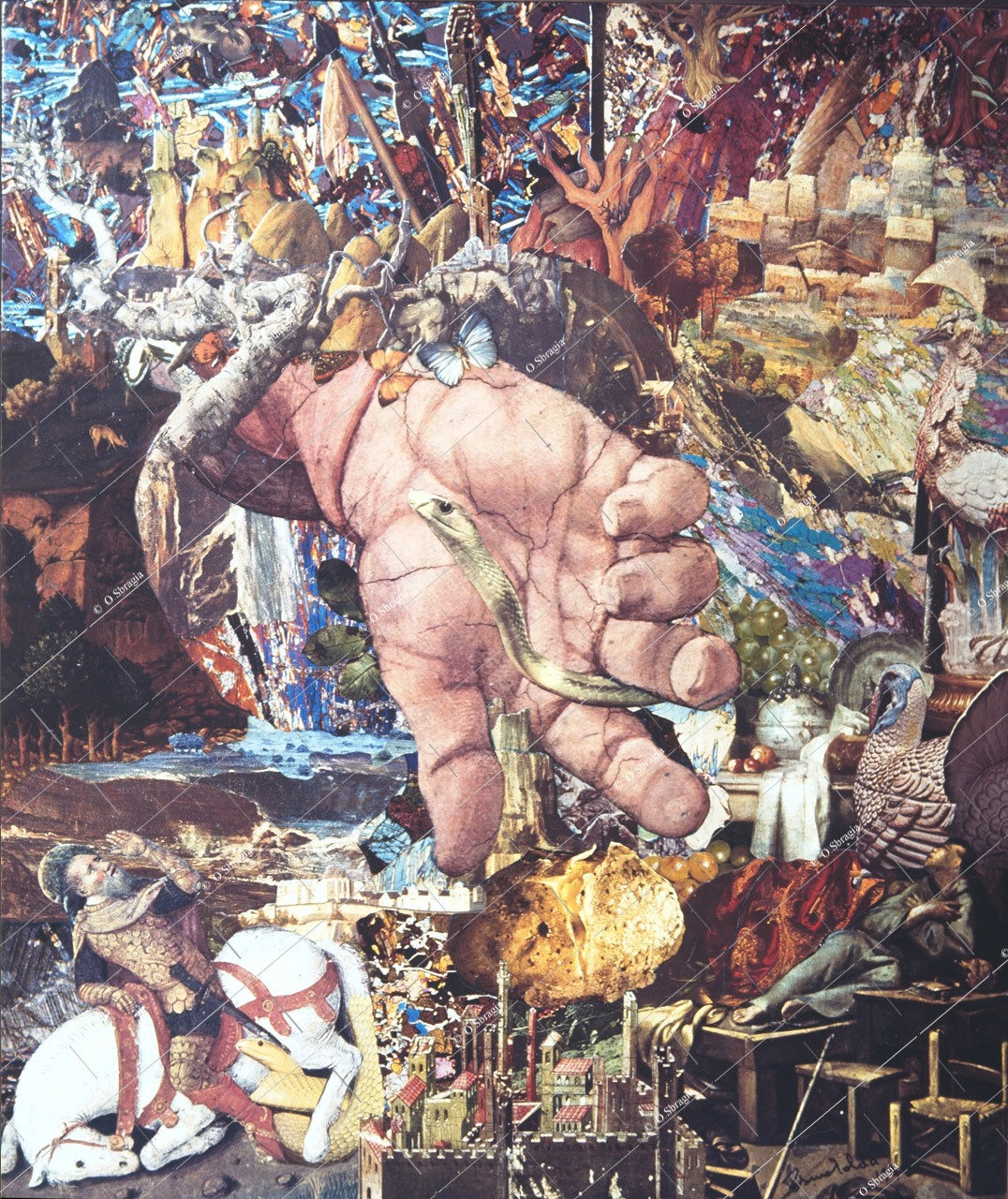

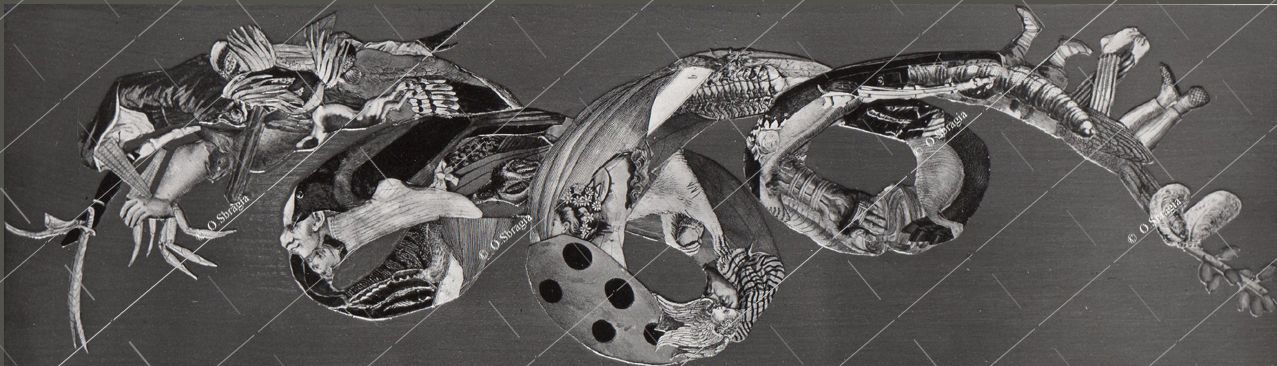

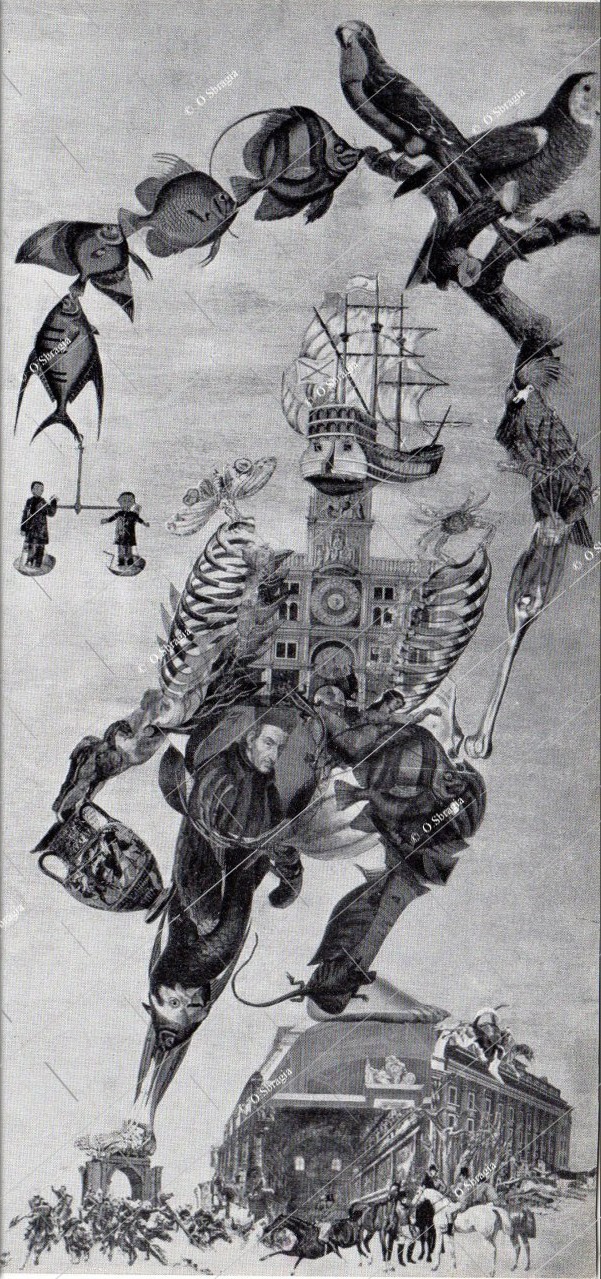

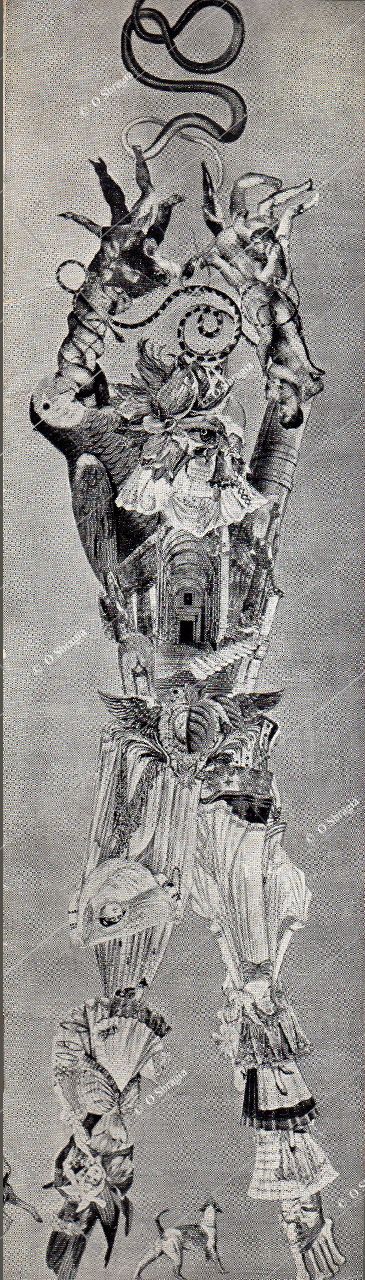

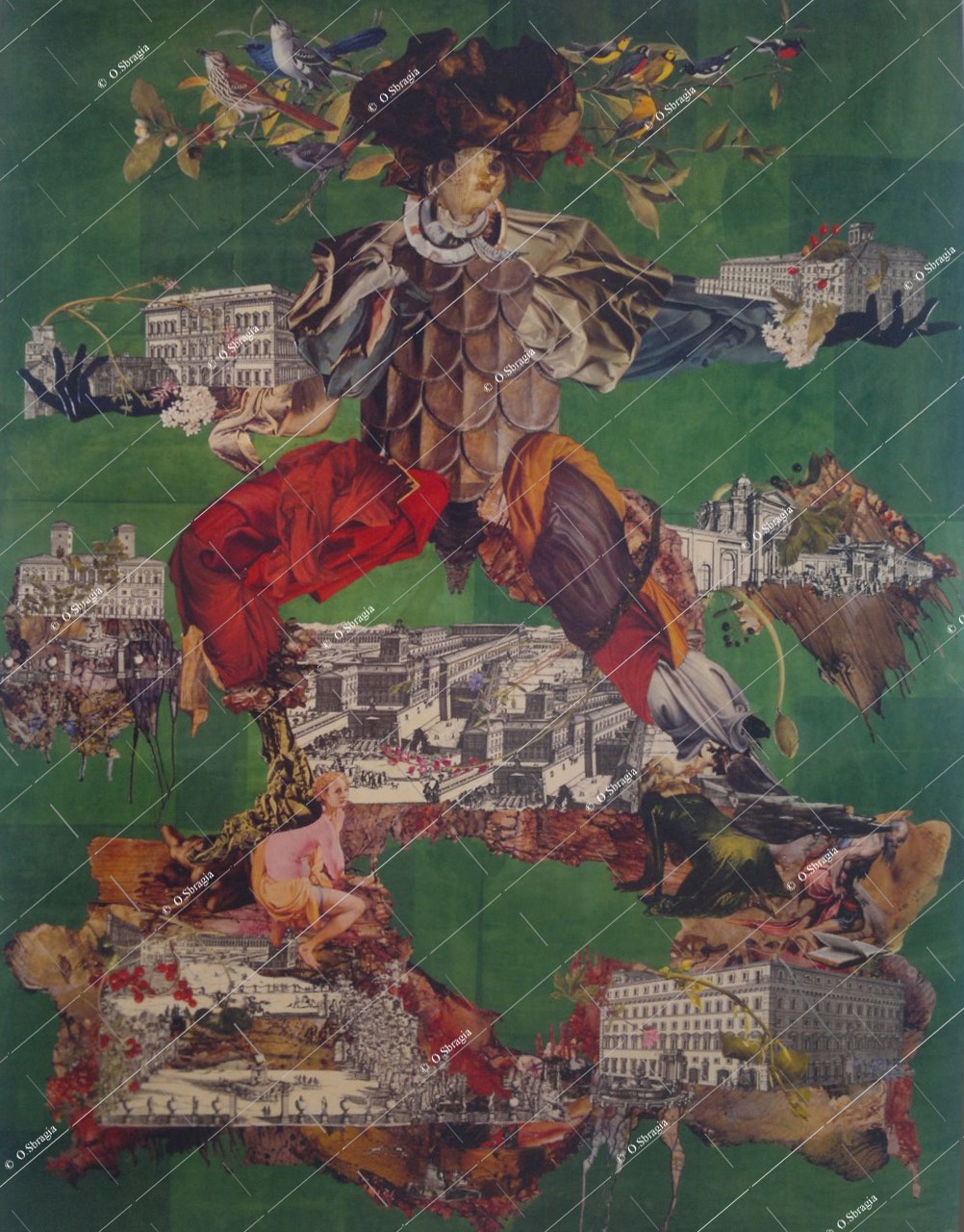

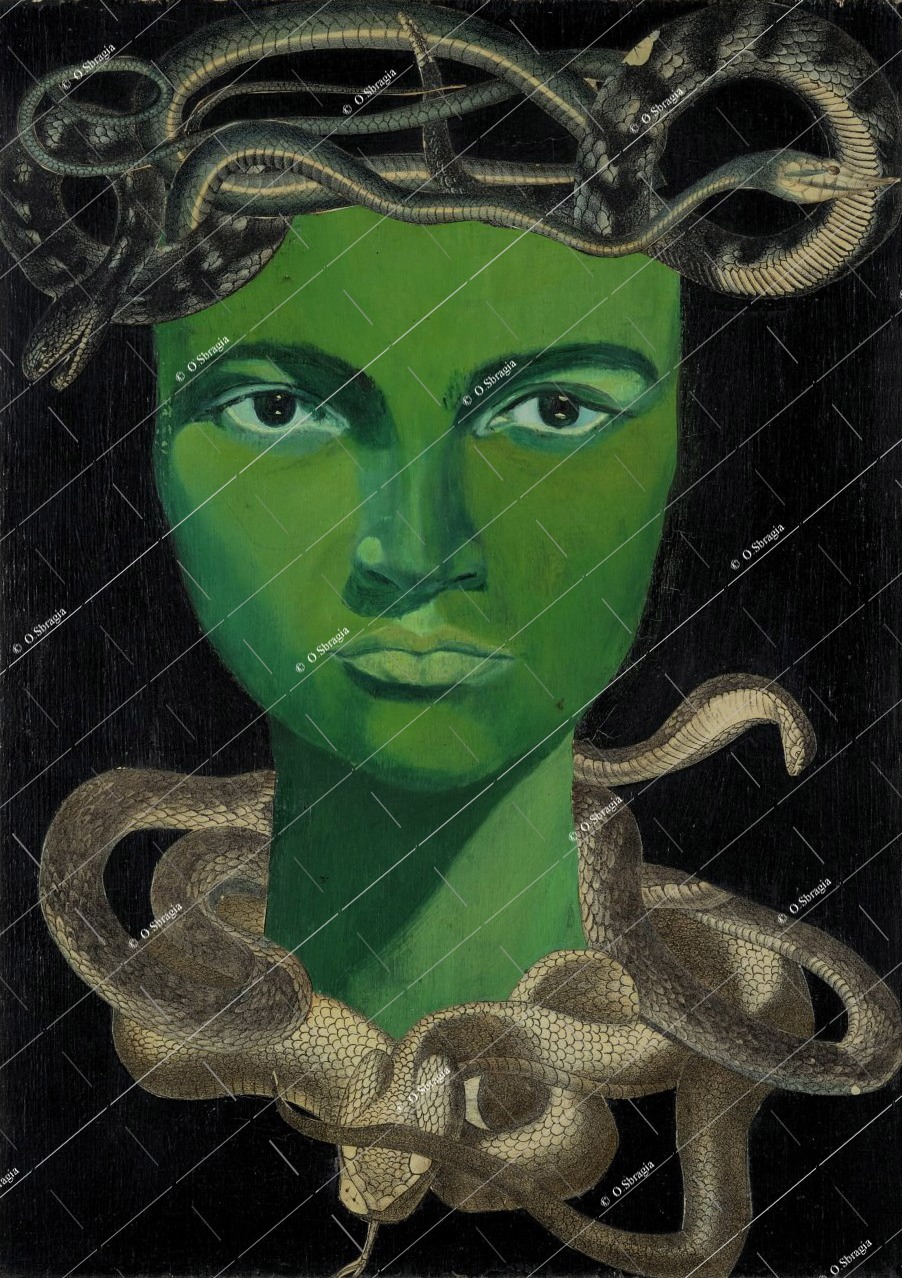

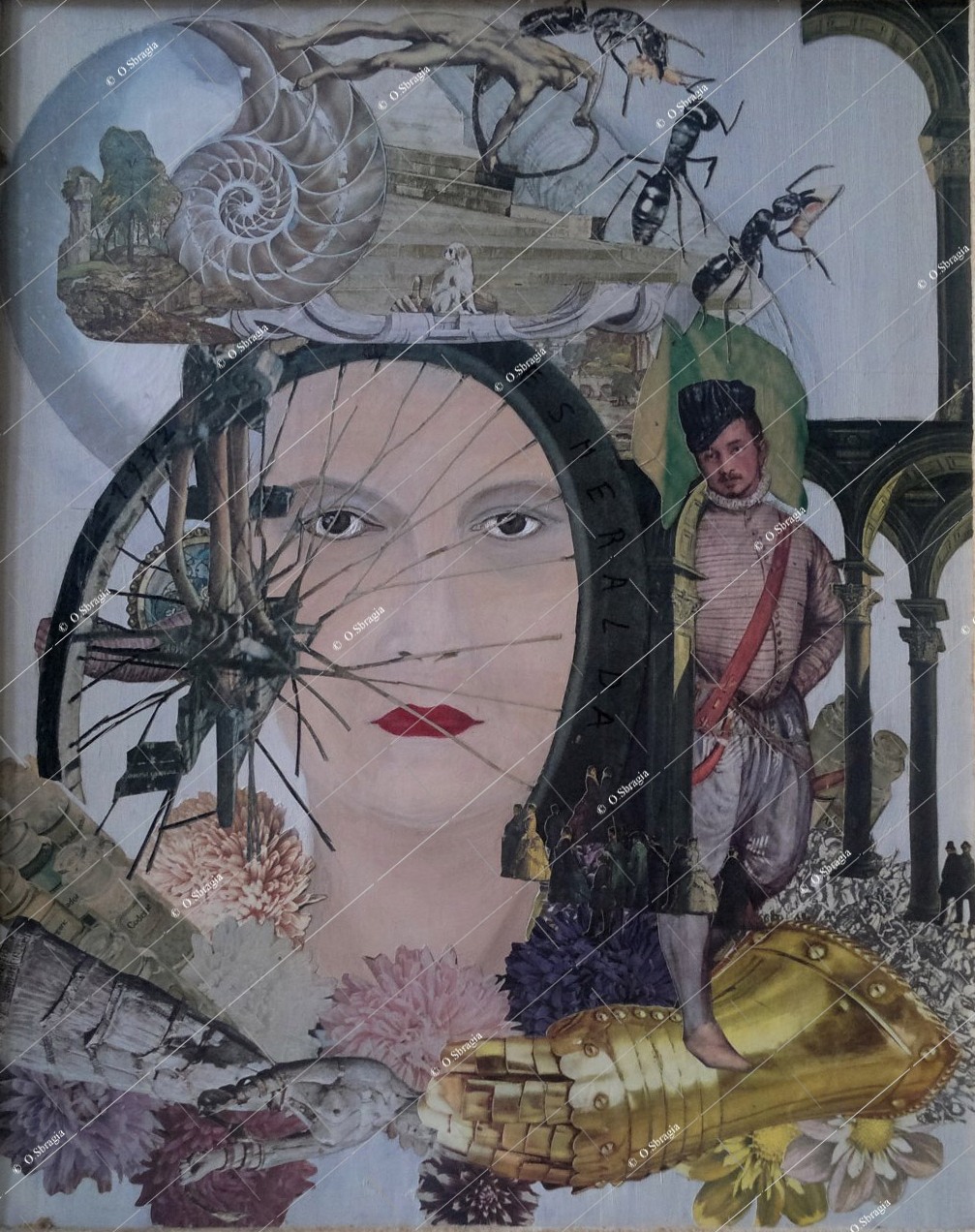

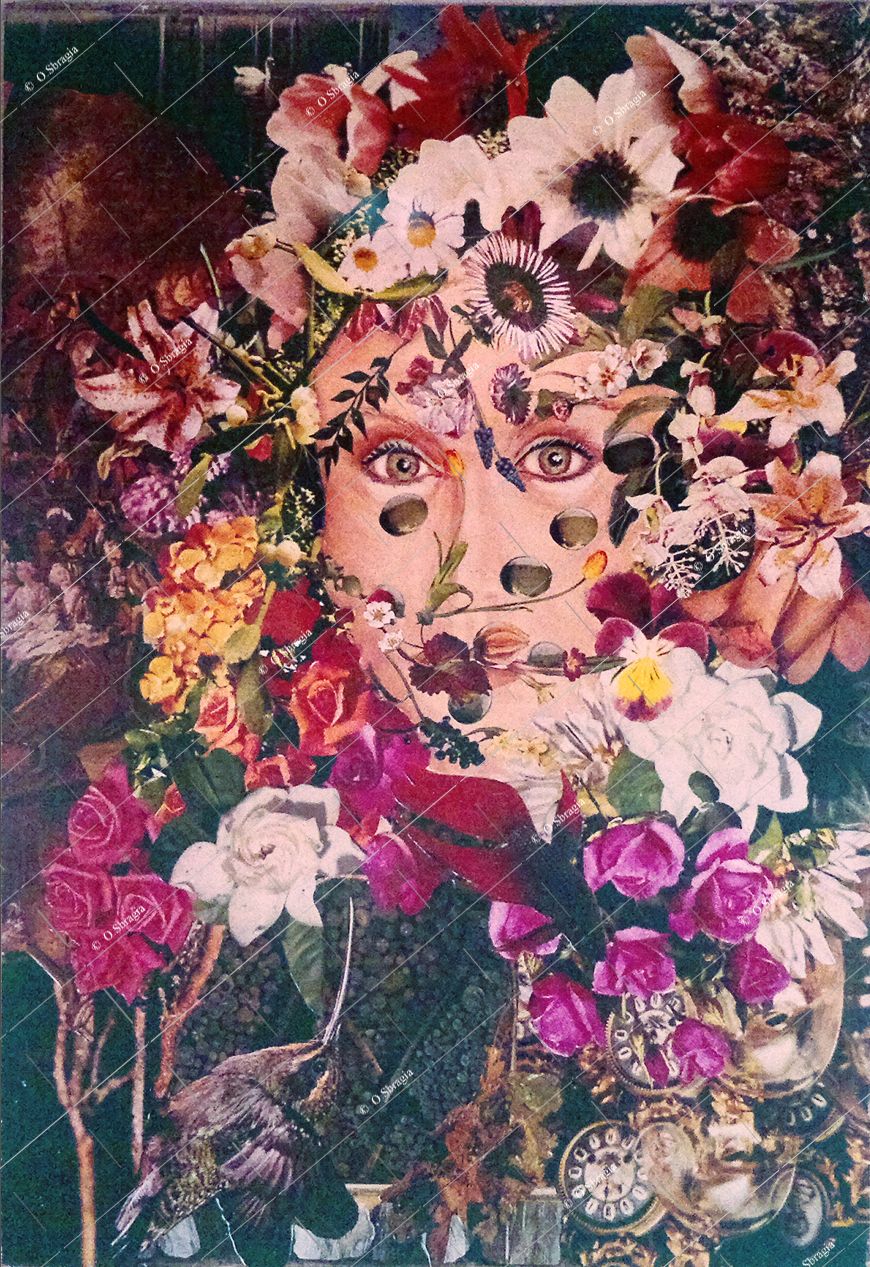

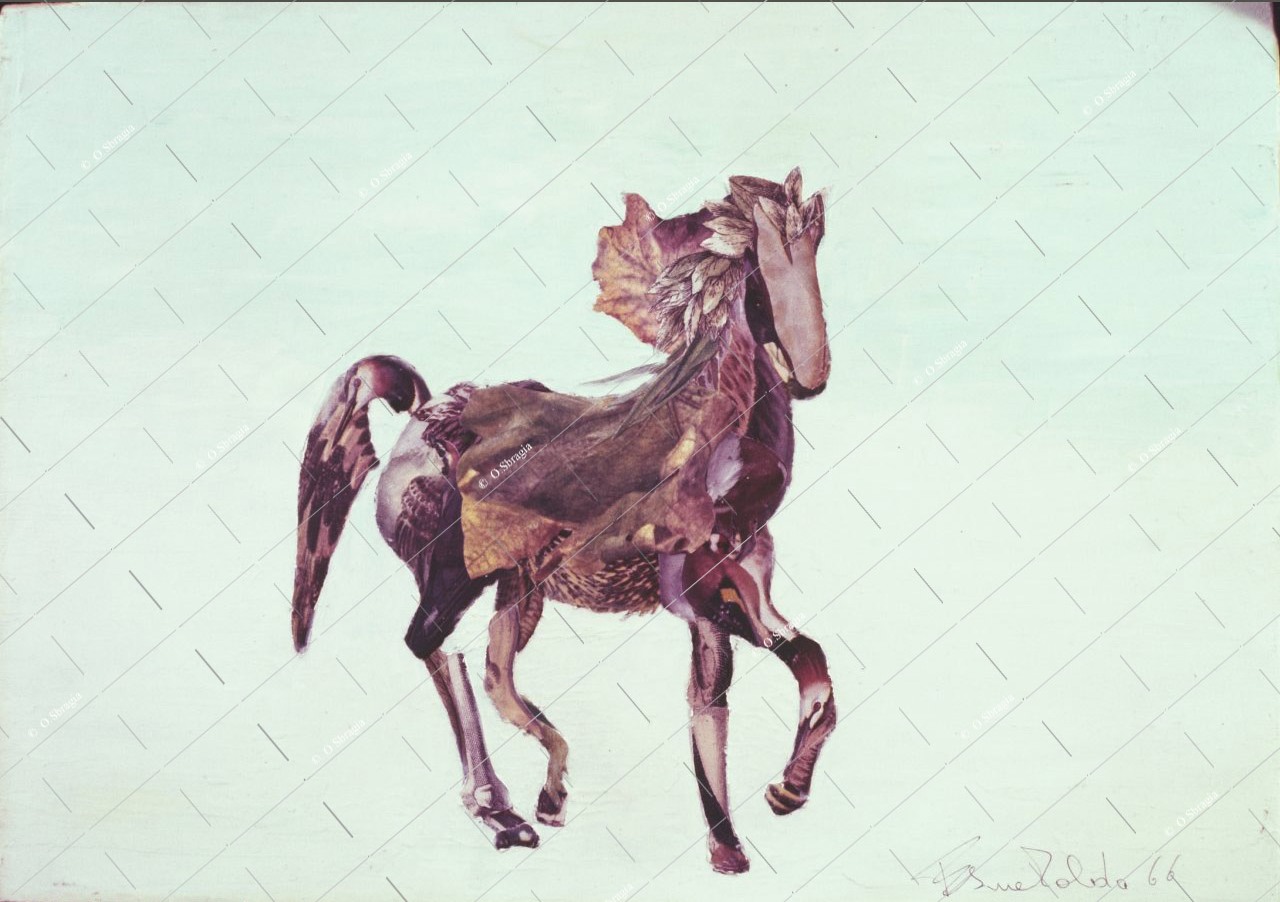

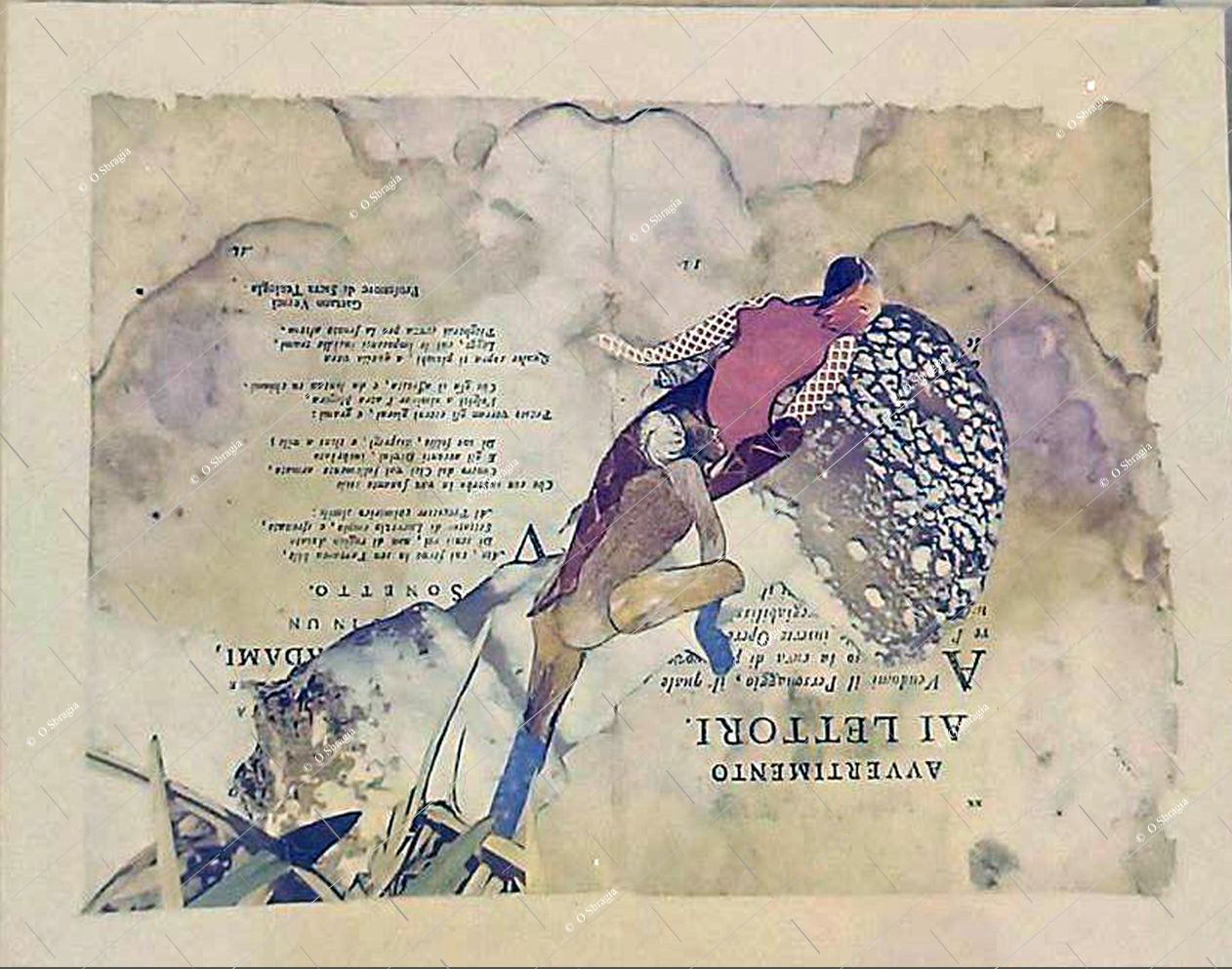

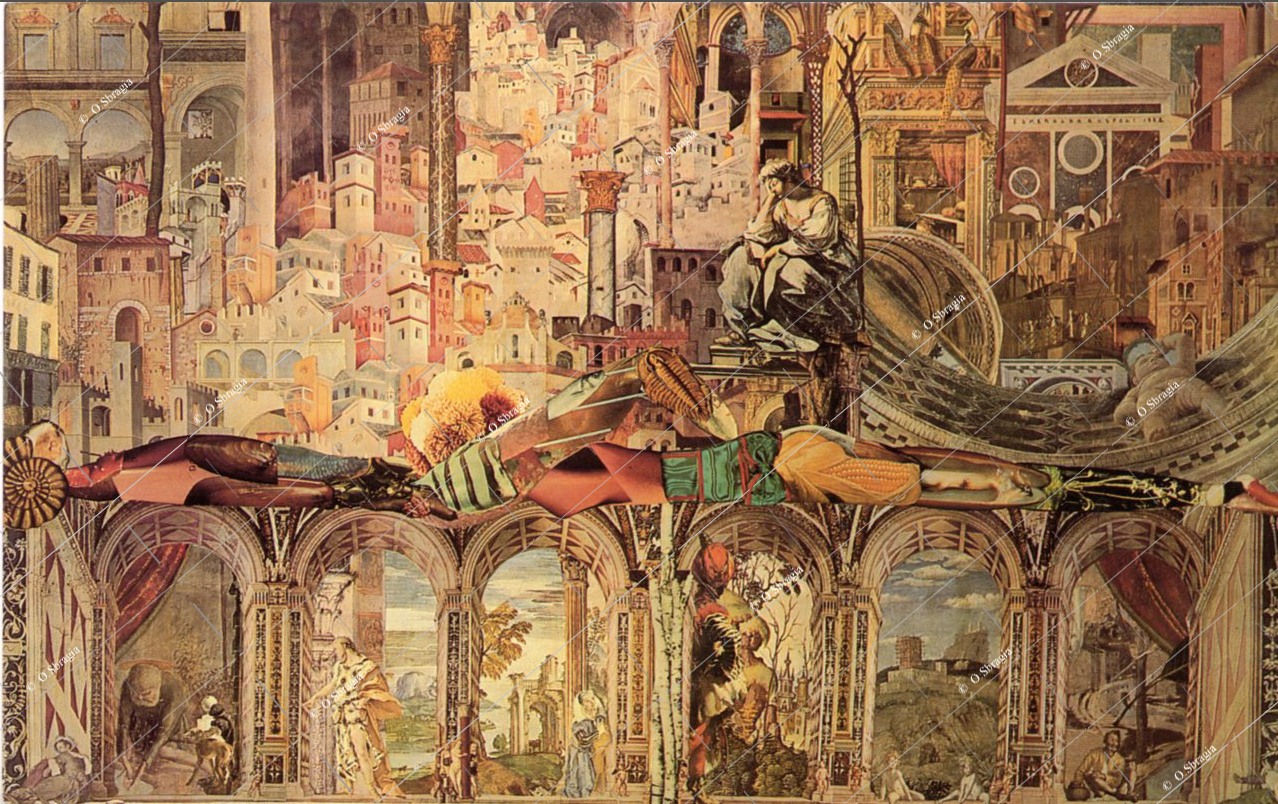

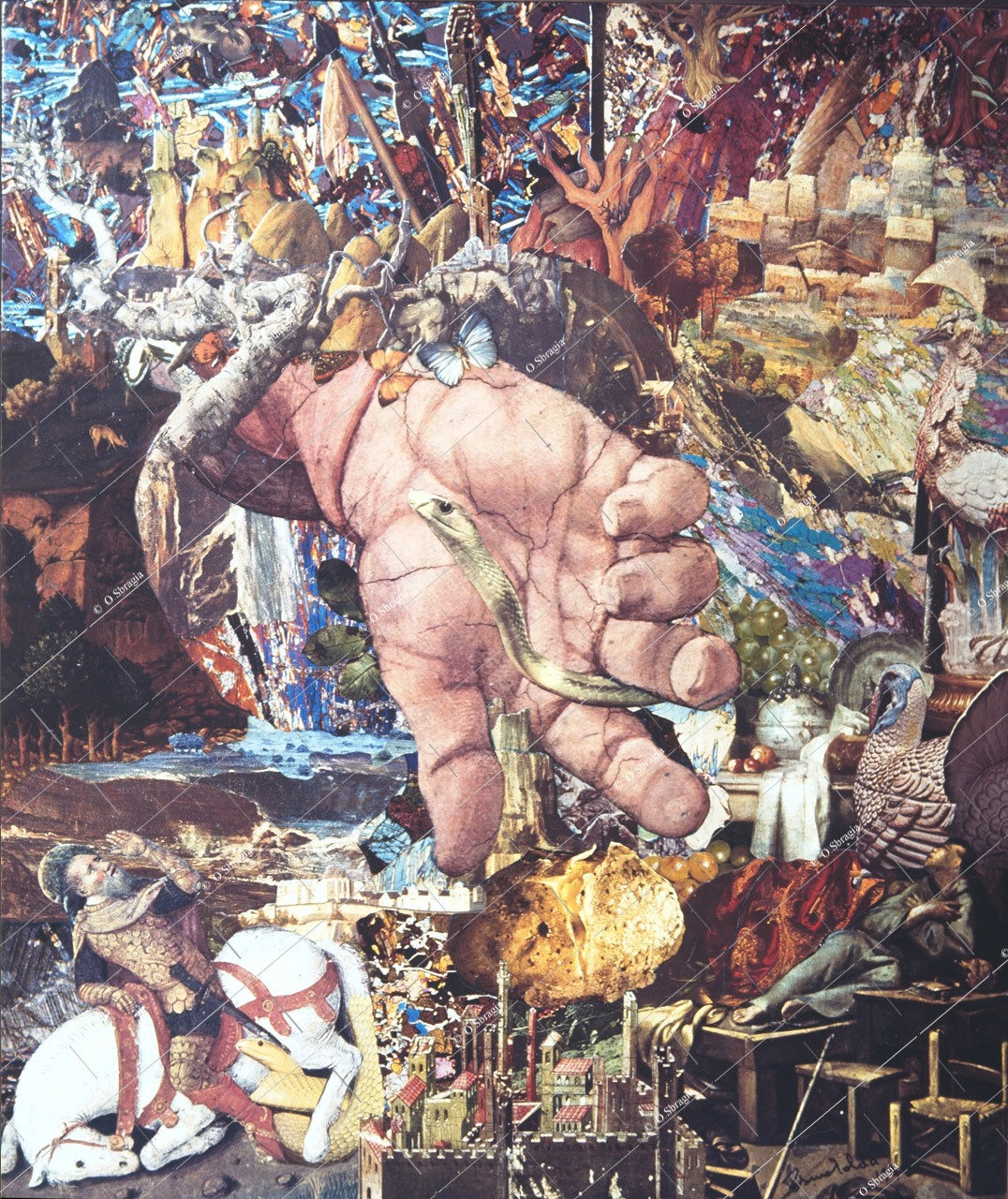

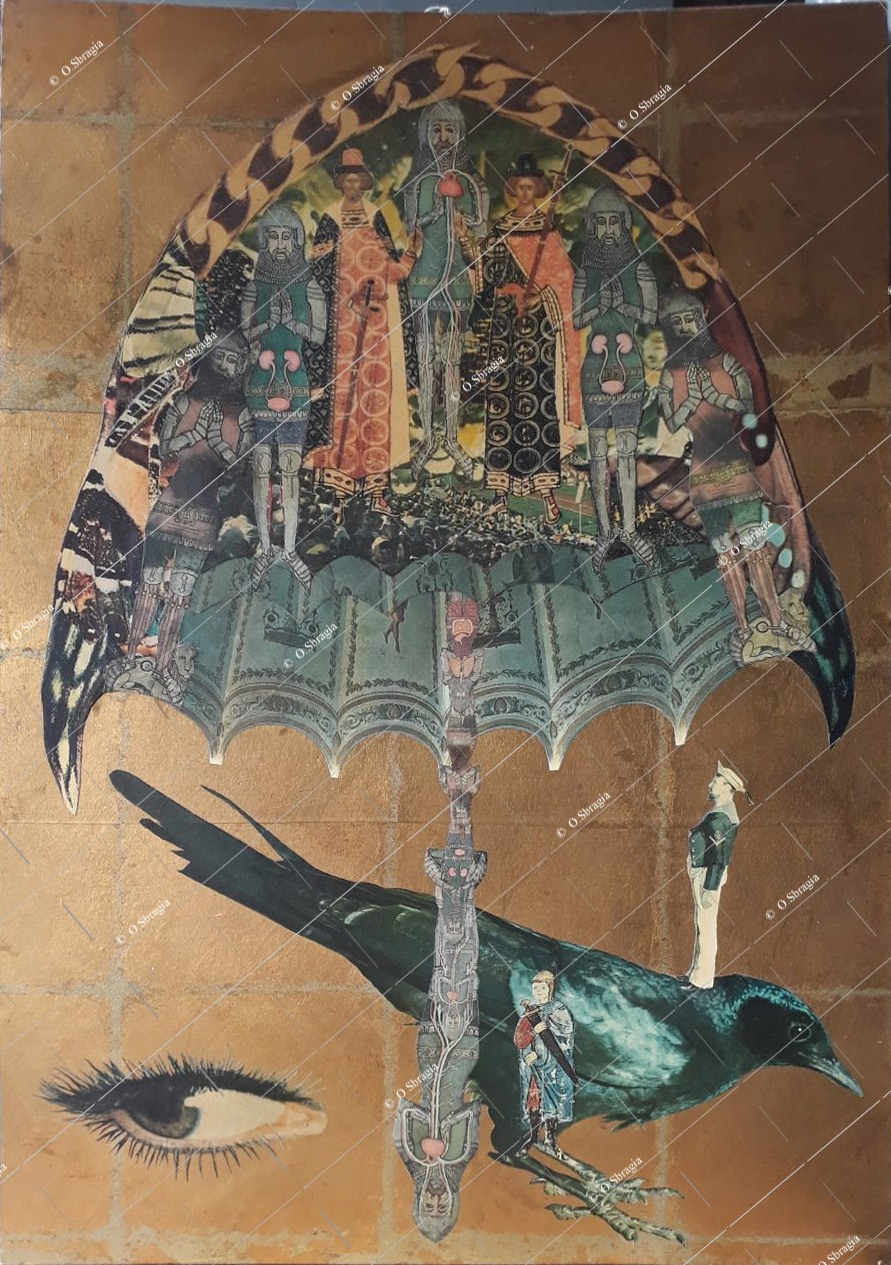

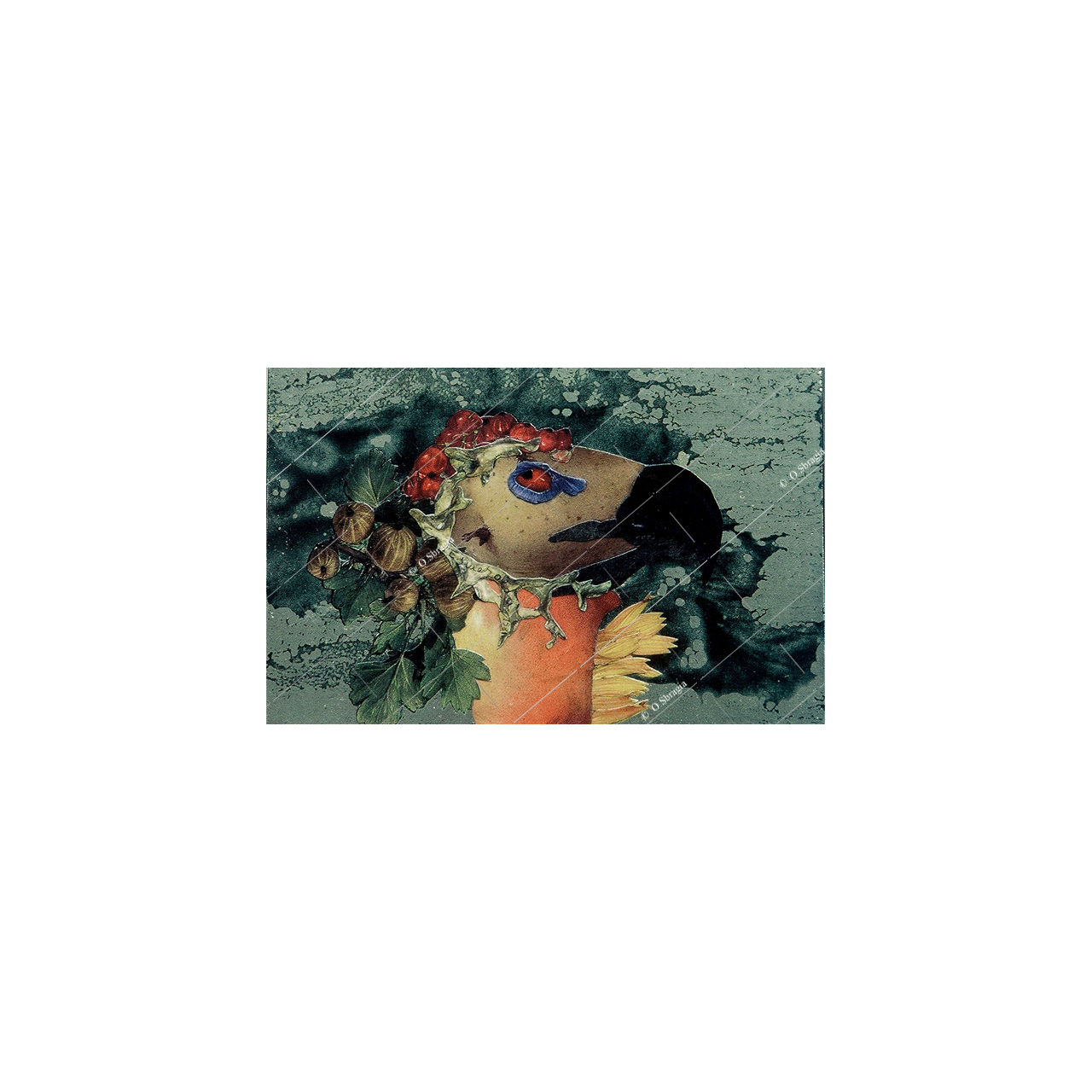

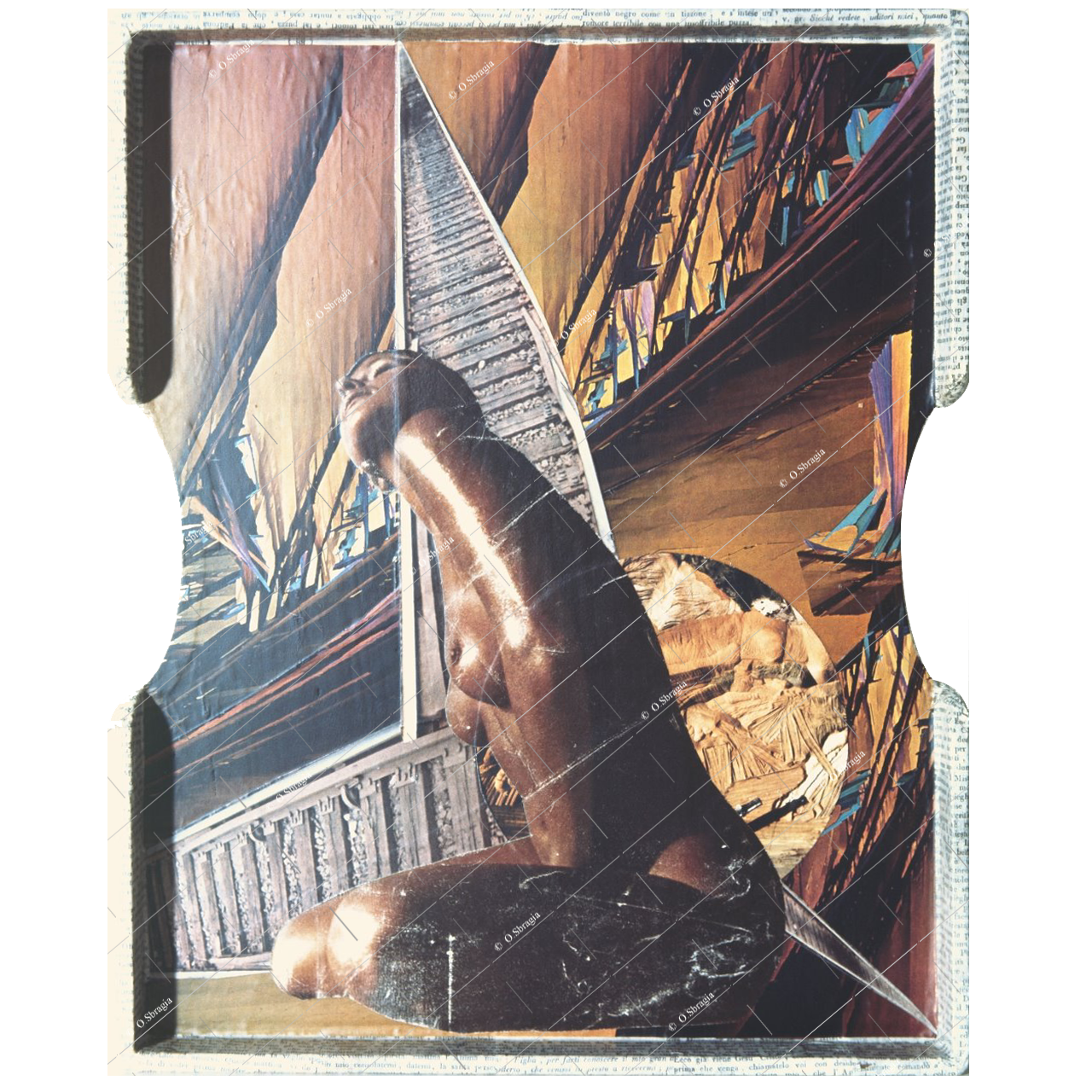

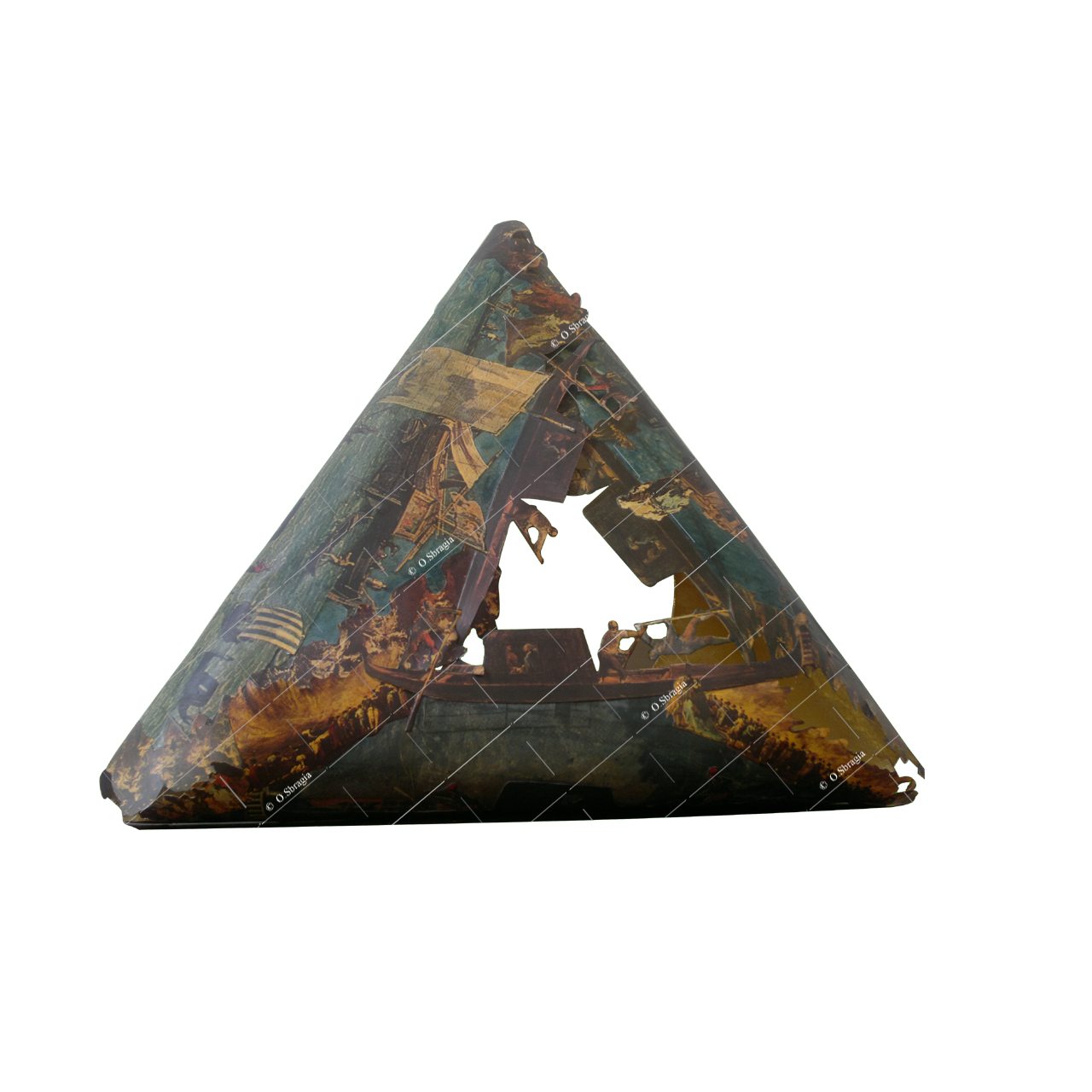

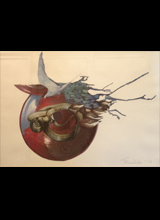

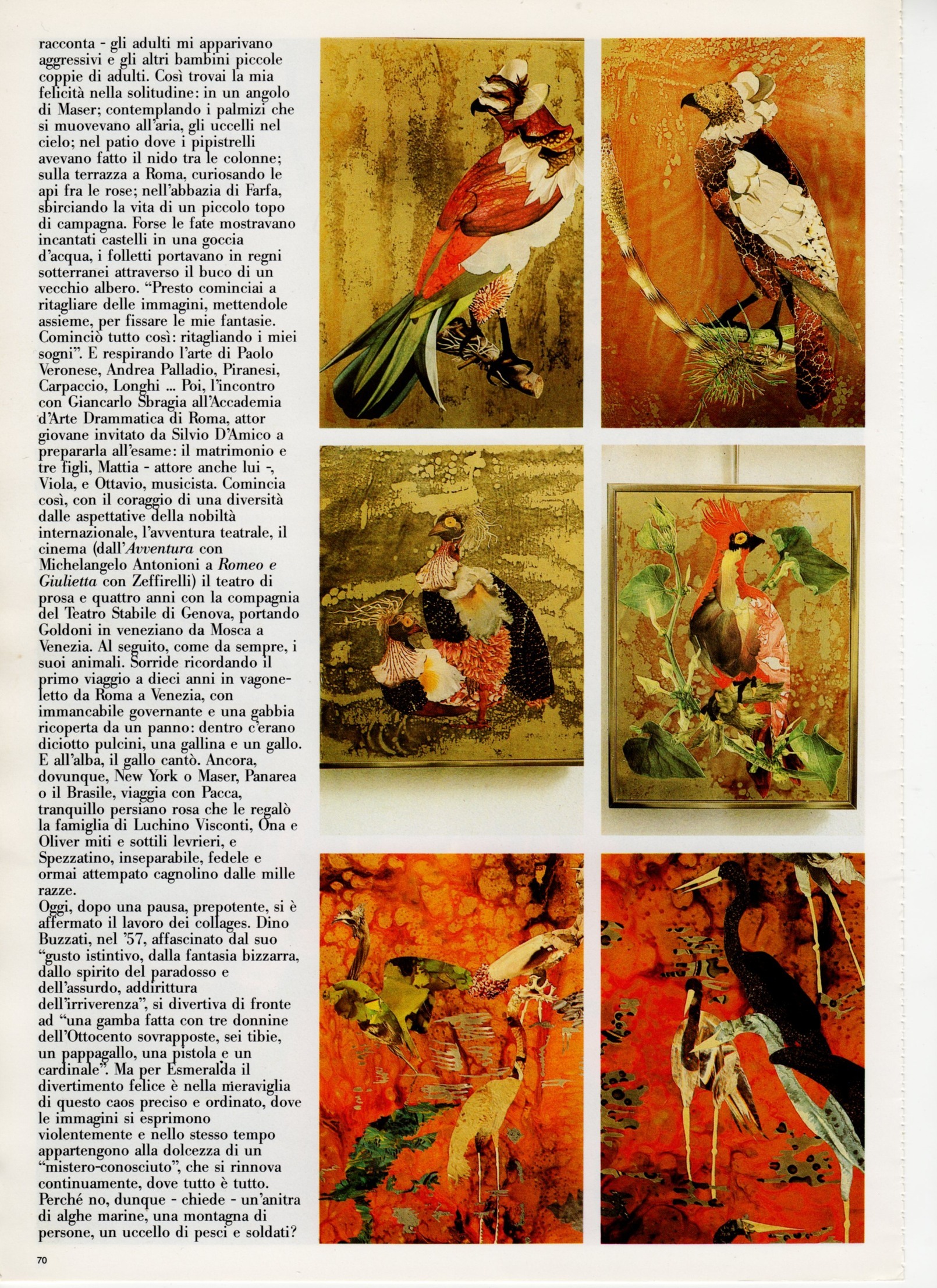

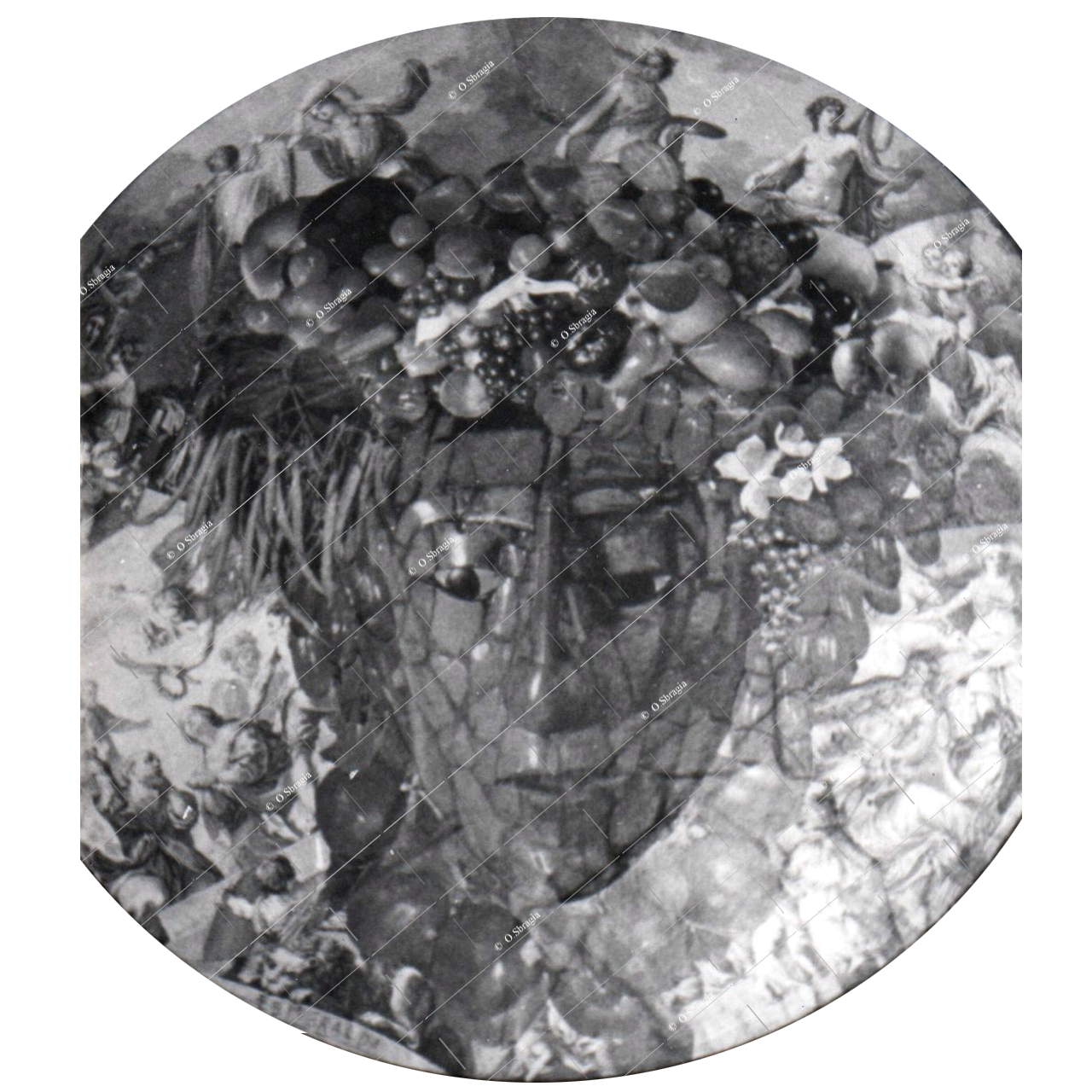

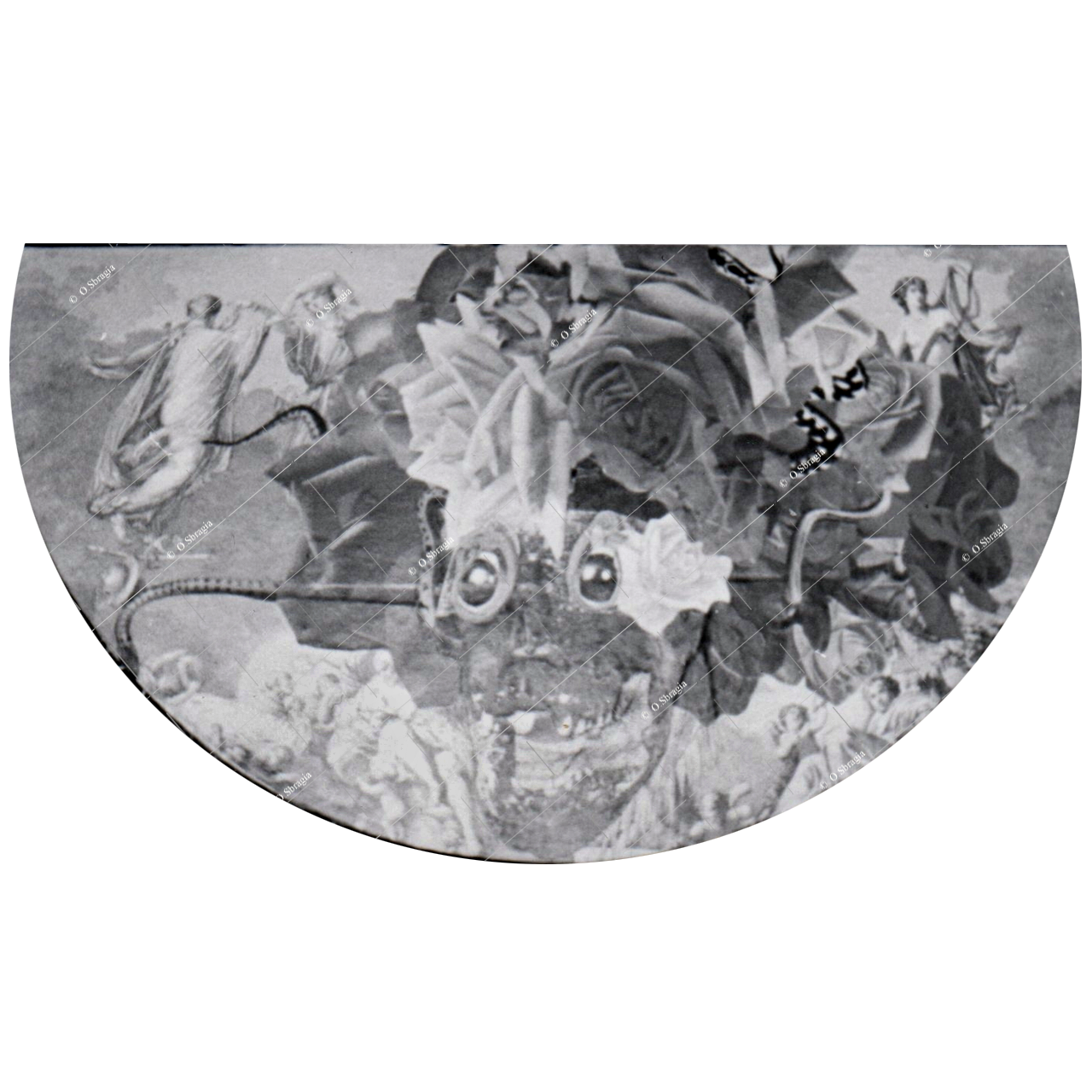

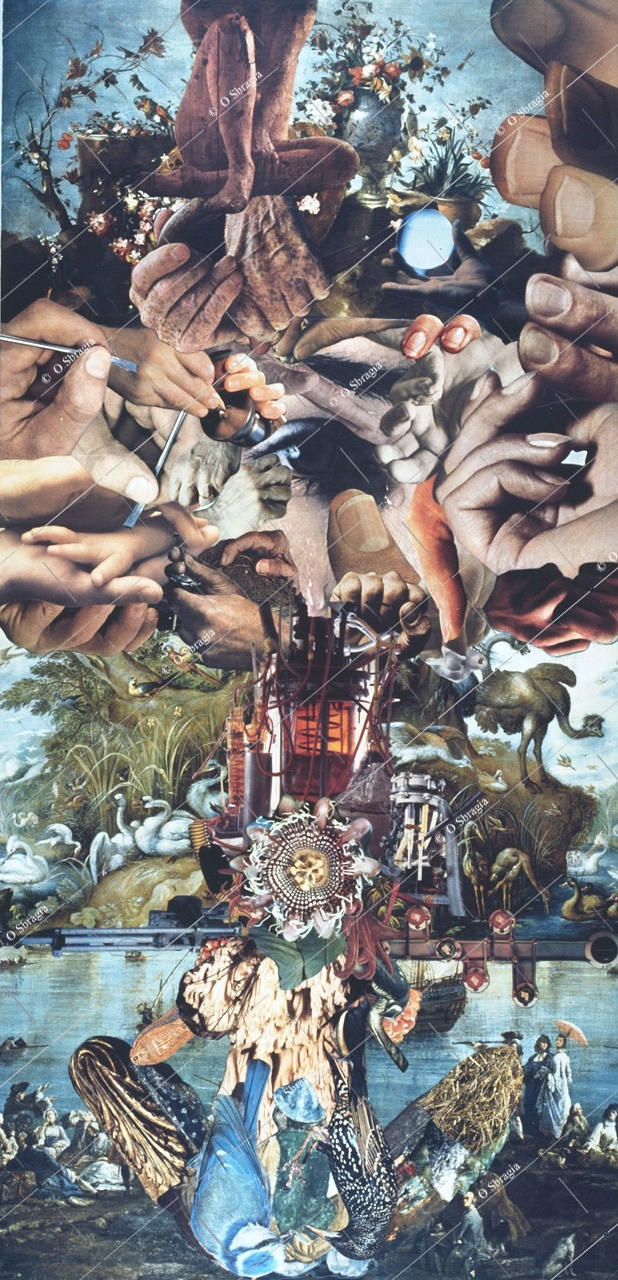

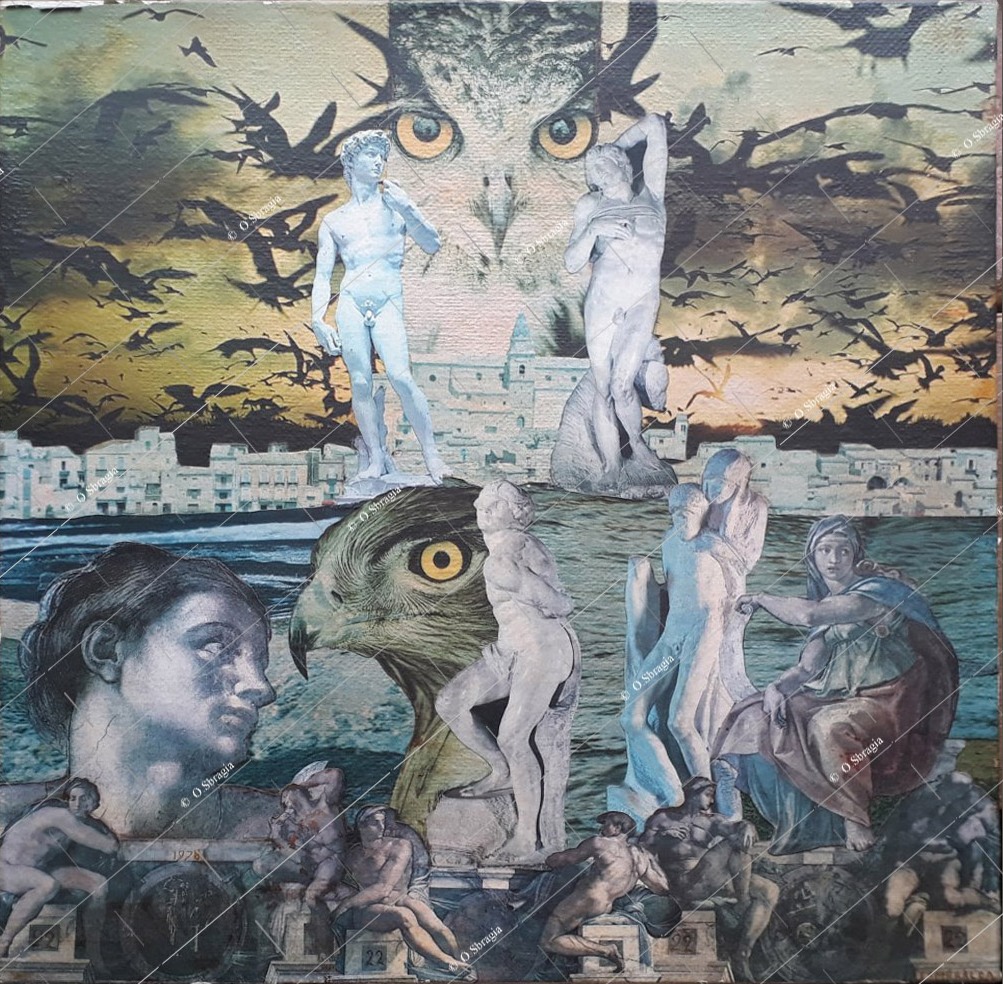

The genie of the cave has not yet emerged from the collages of Esmeralda; however, the result is singular. Her instinctive taste, bizarre fantasy,

certain vague heraldic and geographic reminiscences, a spirit of the paradoxical, of the absurd, and even of irreverence produce tasteful peculiarities

and objects of great decorative quality, both refined and slightly decadent (distantly reminiscent of ruins, landslides, earthquakes, nightmares, Bosch and

Arcimboldo, spiritualistic contributions and organic decompositions). With the passage of time, the game has become more precious and elegant; it has

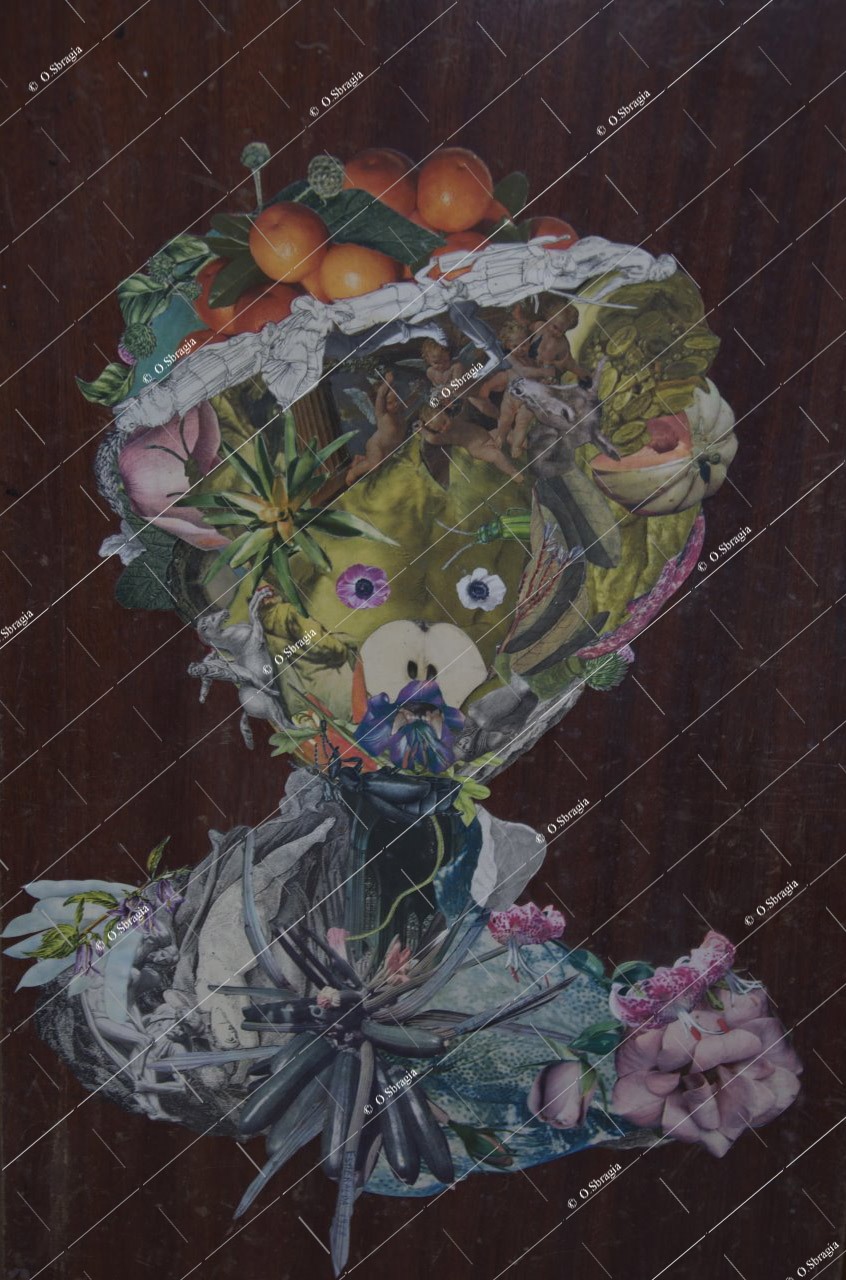

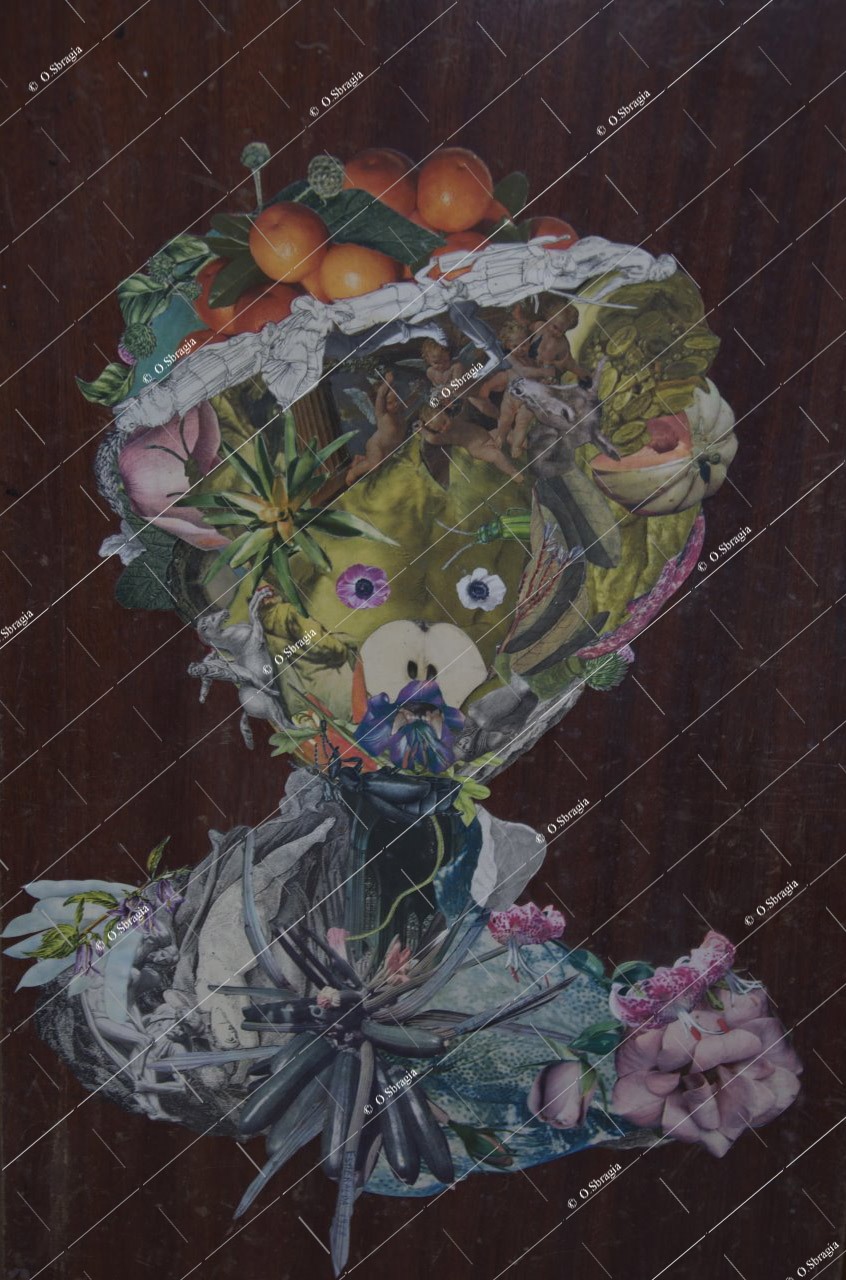

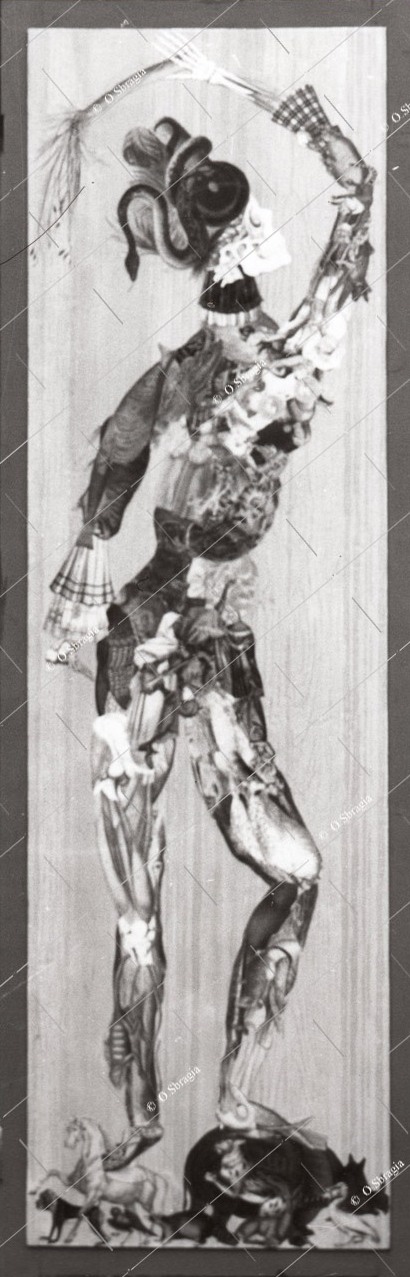

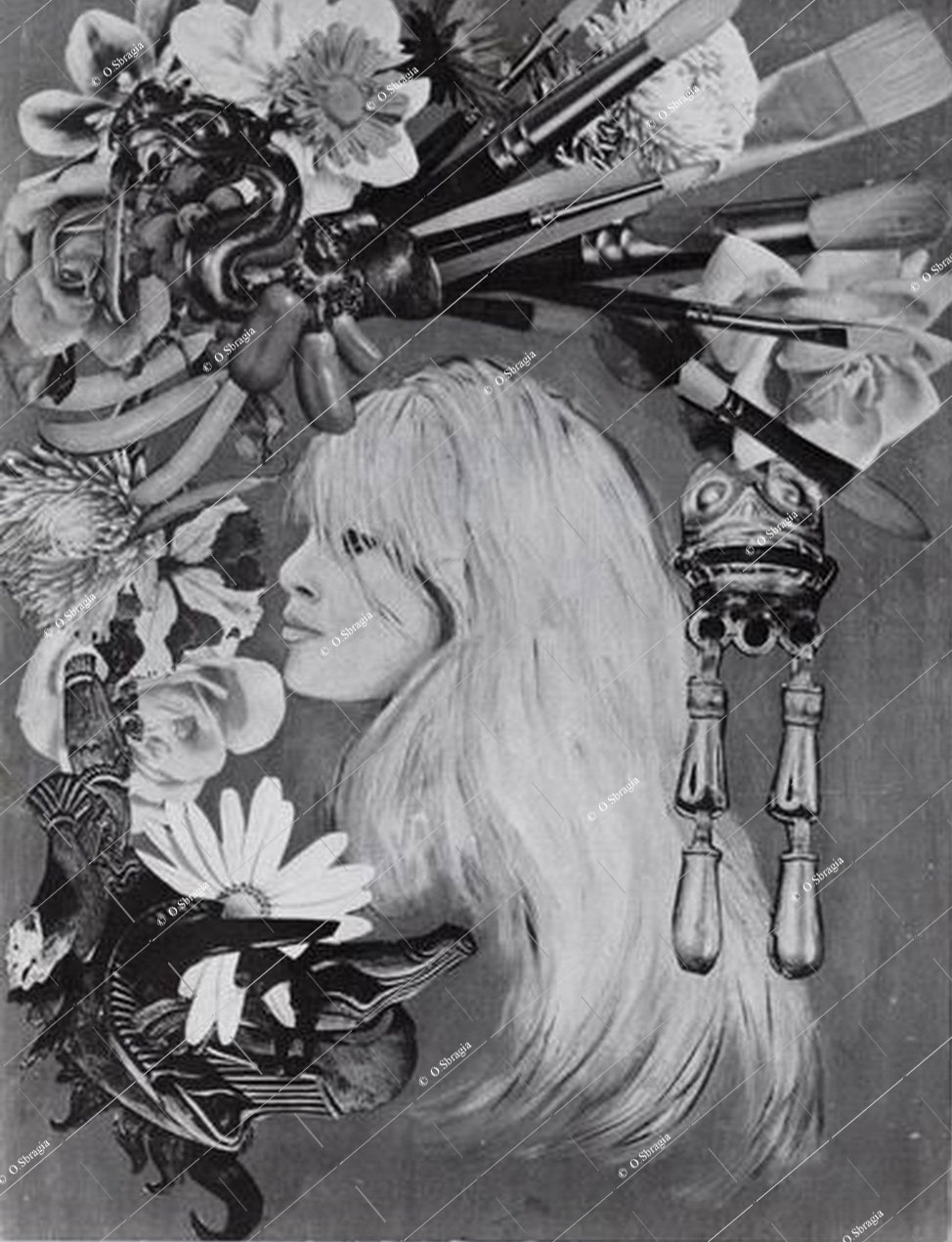

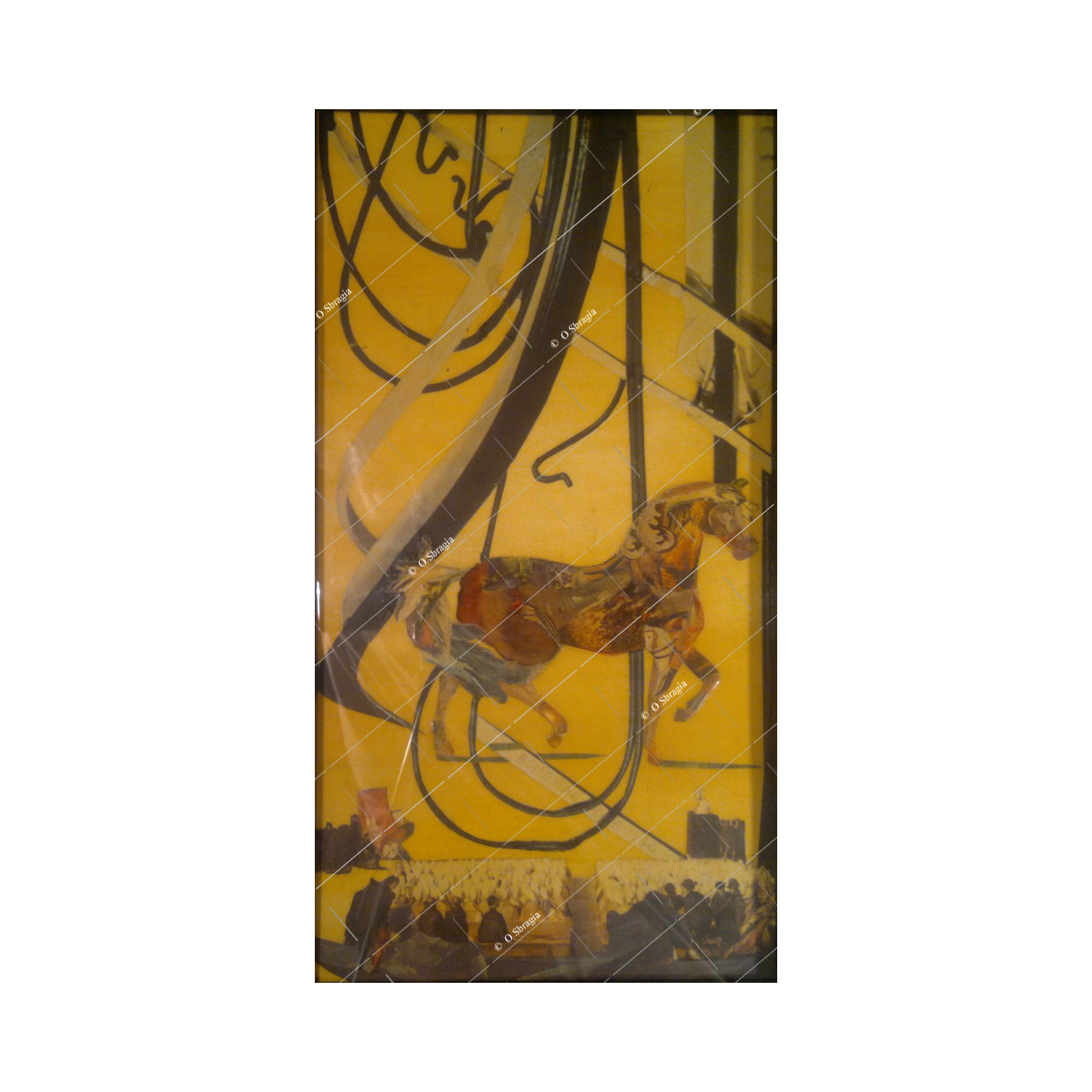

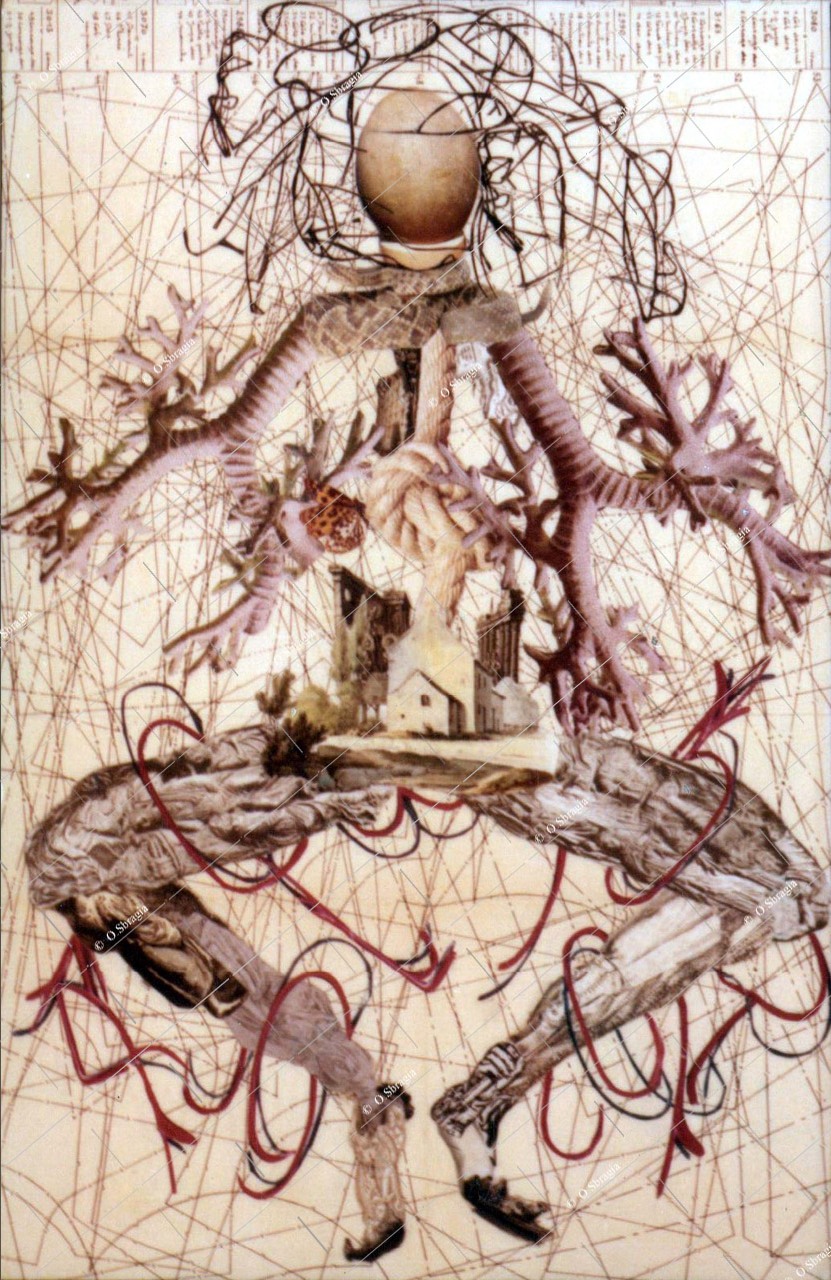

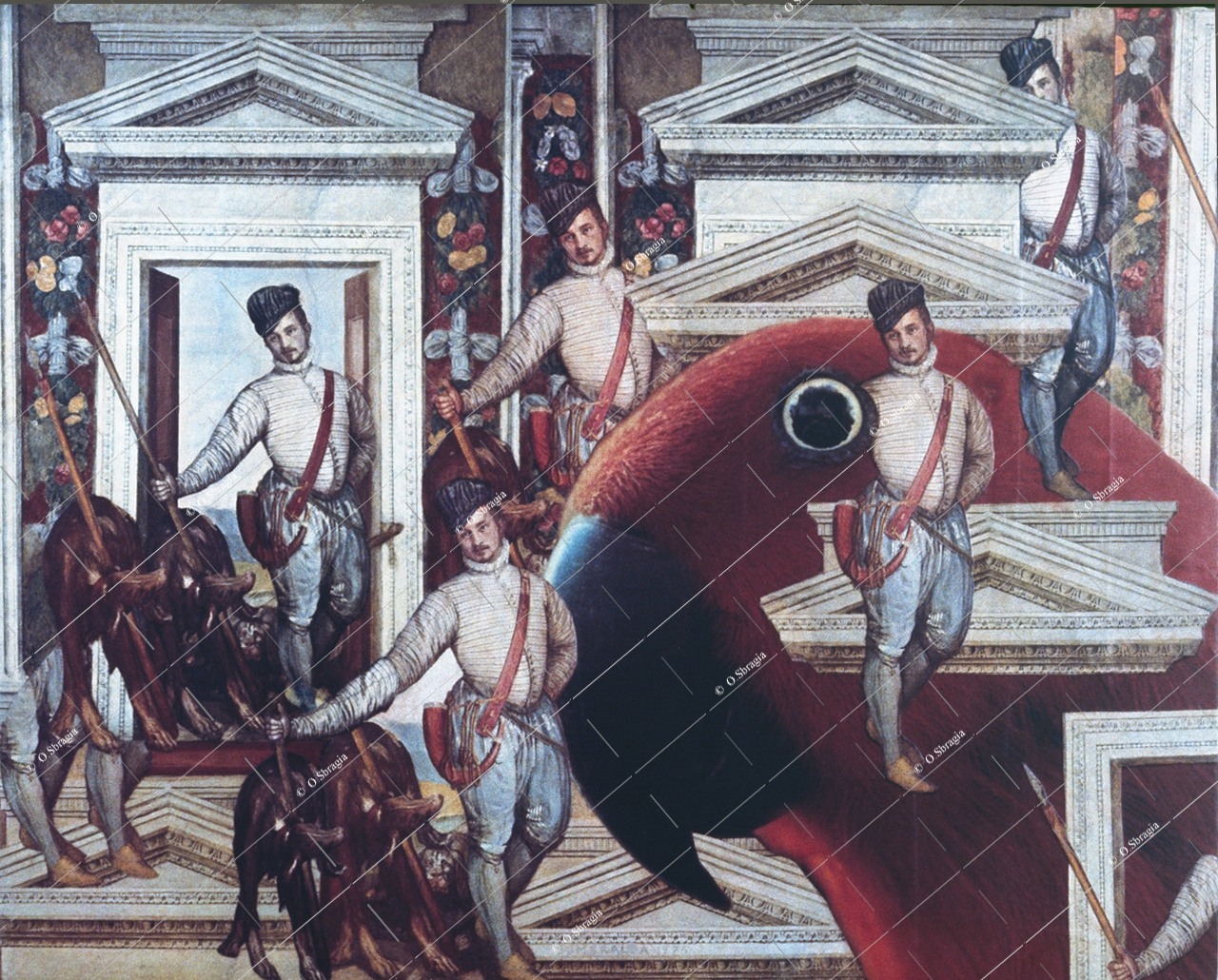

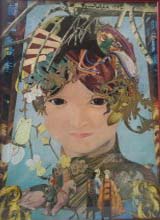

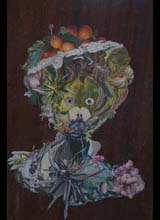

become simplified and more complicated at the same time. No longer surfaces that are entirely covered with images but fantastic constructions or improbable

personages constructed with the most heterogeneous and craziest materials: a leg made with three overlapping ladies of the nineteenth century, six tibia bones,

a parrot, a pistol and a cardinal: an arm made of a Greek vase, half horse, a serpent boa, a Moluccan cockatoo, a slave, a lunar landscape and six human legs,

a head made of a great decapitated vizier, a couple in Empire style and other undecipherable ingredients. Are they human creatures, spectres, dragons,

anatomical charts, legends, hieroglyphs or bewitched cadastral maps?

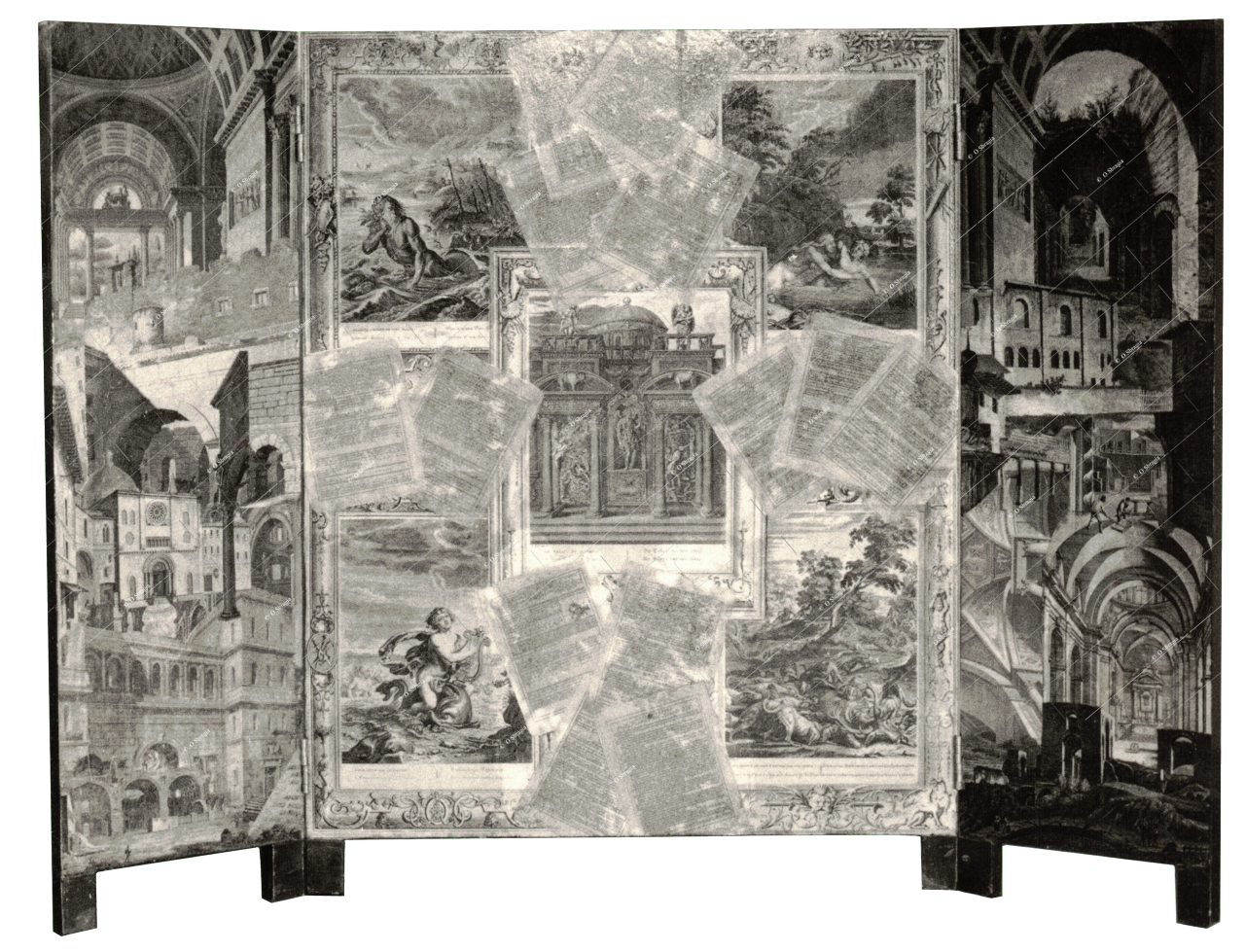

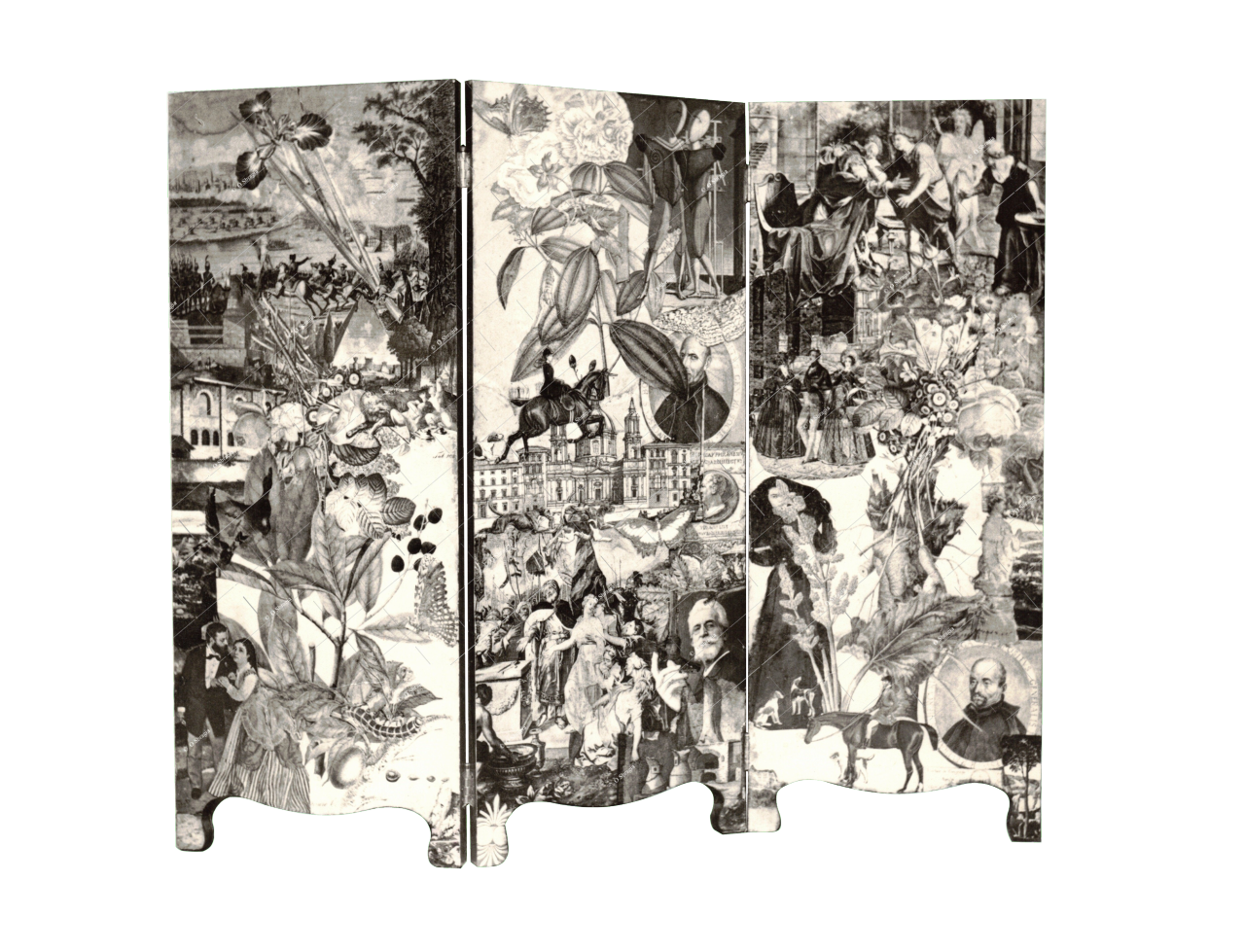

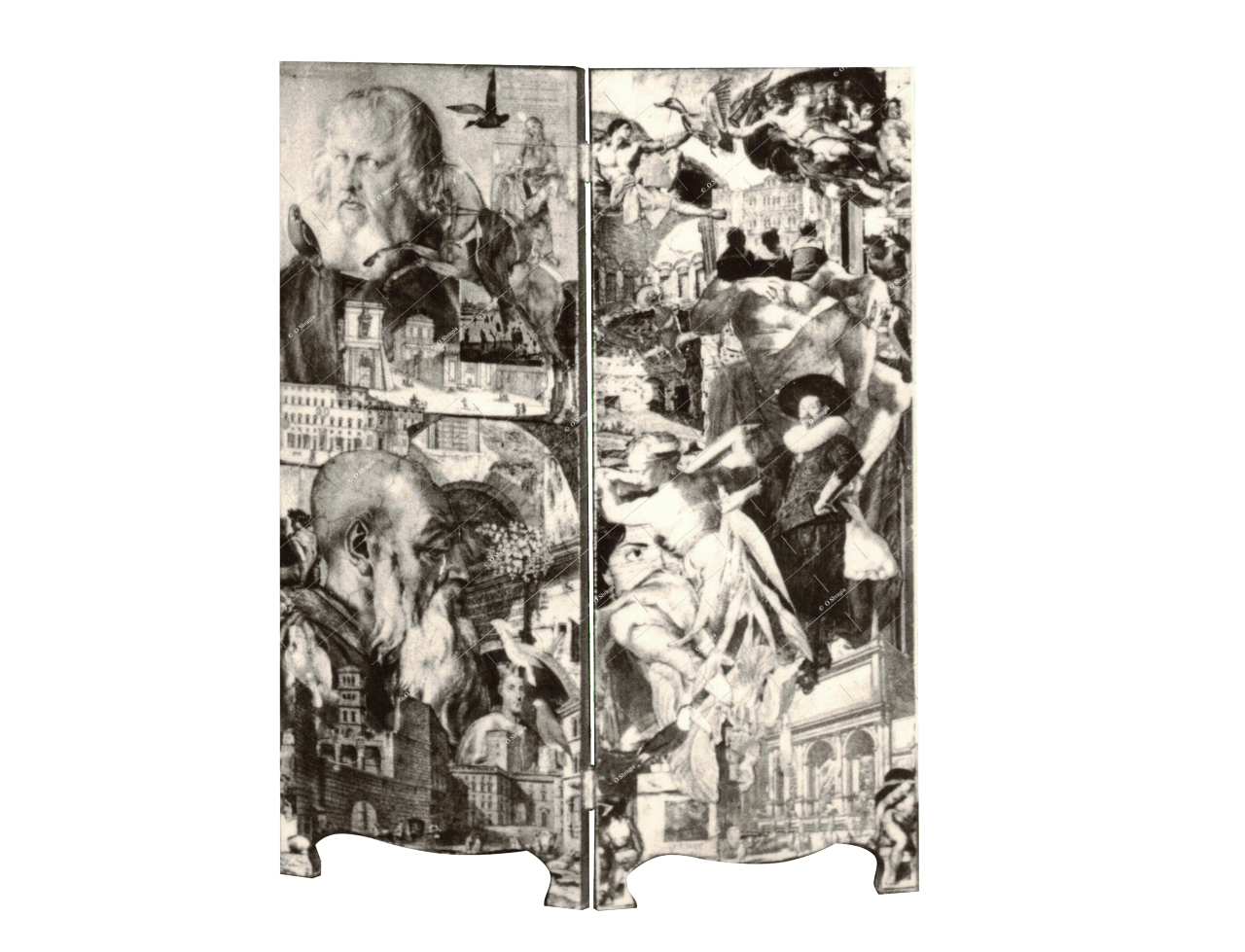

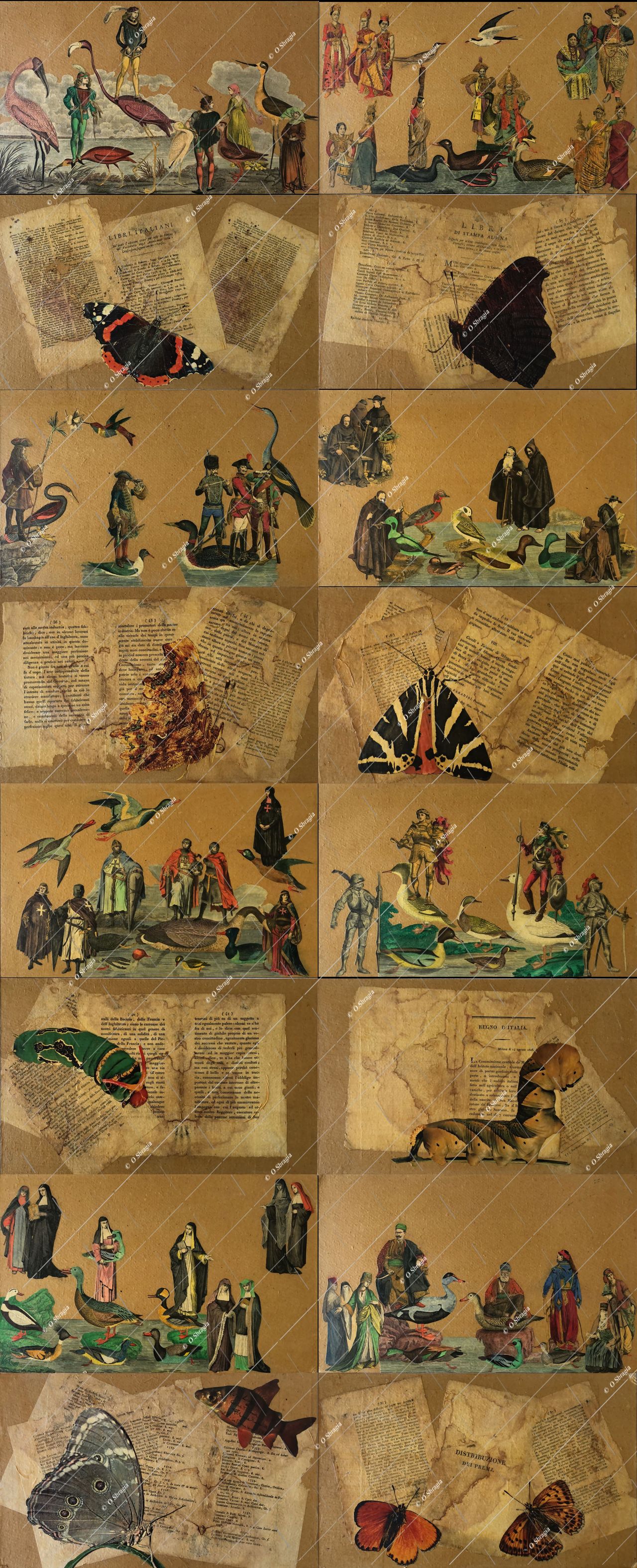

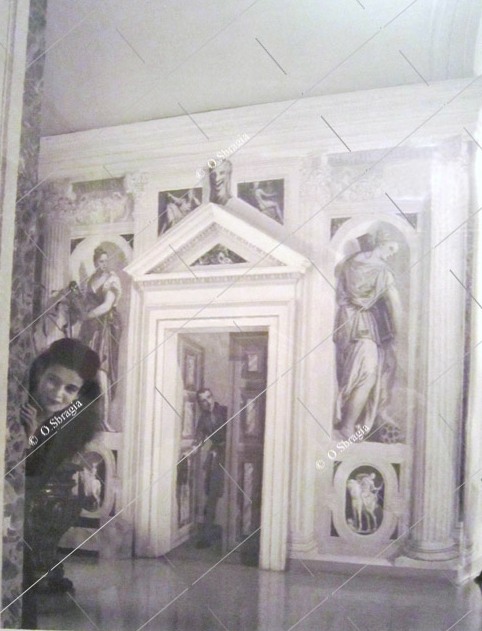

Esmeralda began many years ago decorating a door of the famous Villa Maser with cutouts from illustrated newspapers and prints. Then, screens and cupboards.

Until, one rainy day, the thought occurred to her to create a personage made of the strangest of things. A personage who was the founder of an entire generation

of amiable monsters.

"The thought has never occurred to me to dedicate myself to painting in the future, " says Esmeralda Sbragia, "I am not some hidden genius of the paintbrush,

I'll continue to make collages if they are liked, and if they are not, I'll make them for myself, on my cupboards, on my doors".

Lastly, a warning: if the genie of the cavern (and of treasures) has not yet come forth from Esmeralda's fantasies, this does not mean that her iconographic

rÚveries are lacking, albeit to a minor degree, their own secrets.

For example - and this we do know - there is a lightning rod that she decorated which on certain evenings - especially in the months of September and October

- emits faint but sweet sounds; a decorated storied casket (in the literal sense of the word) the sight of which calms headaches; and a huge wooden tray

(perhaps the most interesting object) whose figures - for the most part, shells, small rodents and field flowers - when exposed to the light of the second

quarter moon, move alone as if they were alive, as long, logically, as there is total silence.

[hide the article]

Giornale d'Italia, 3 February 1957

Four Painters and the Collages of Esmeralda

[read the article]

[hide the article]

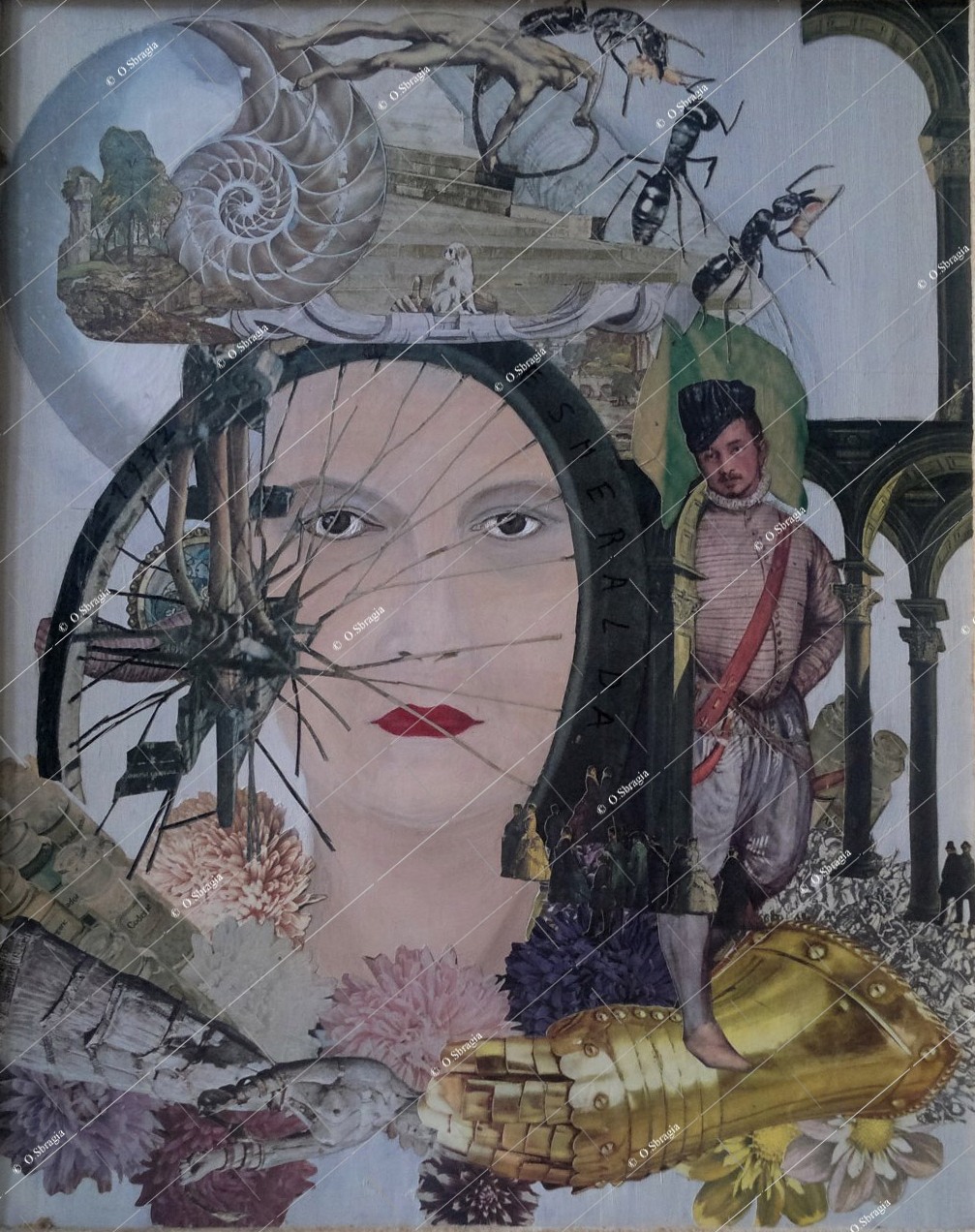

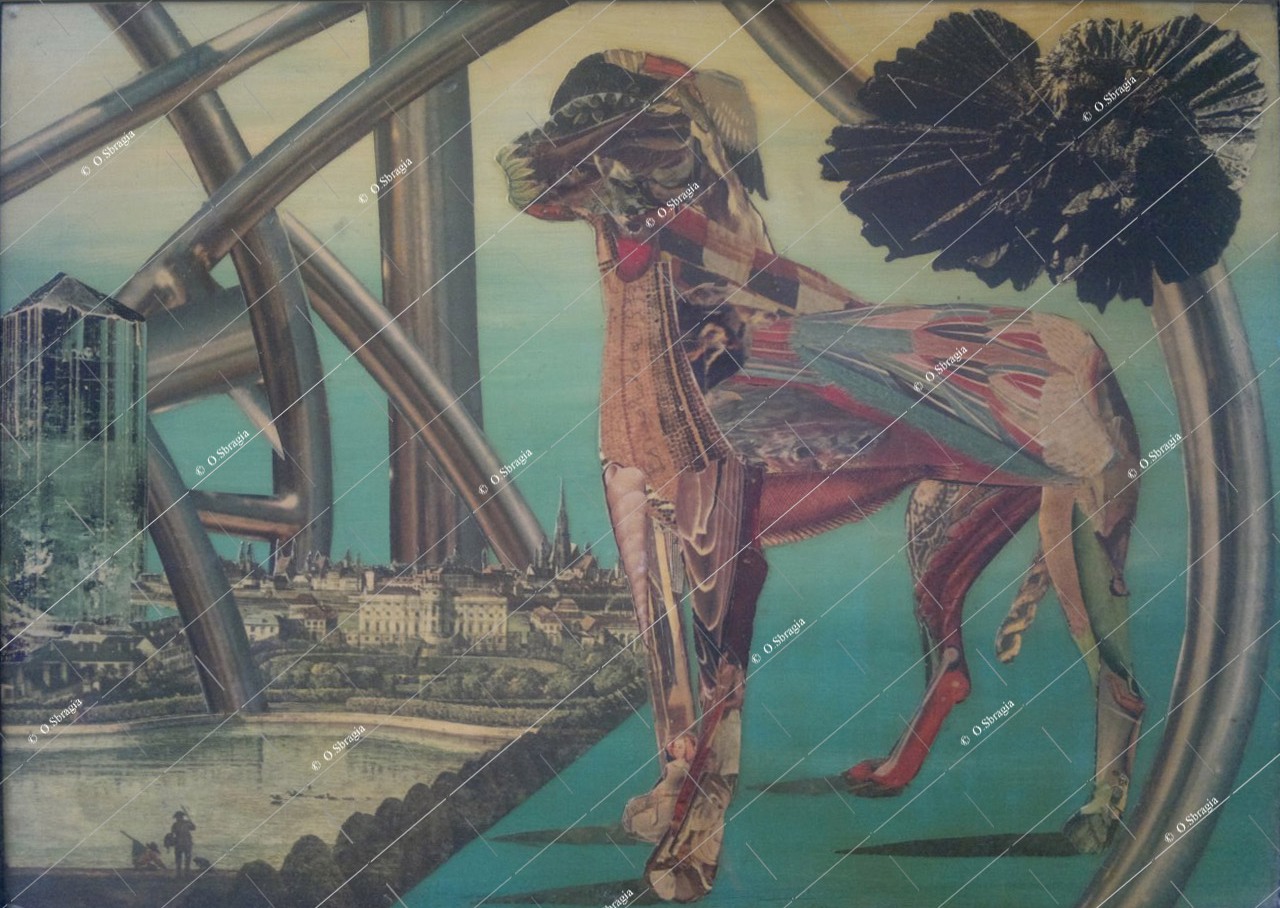

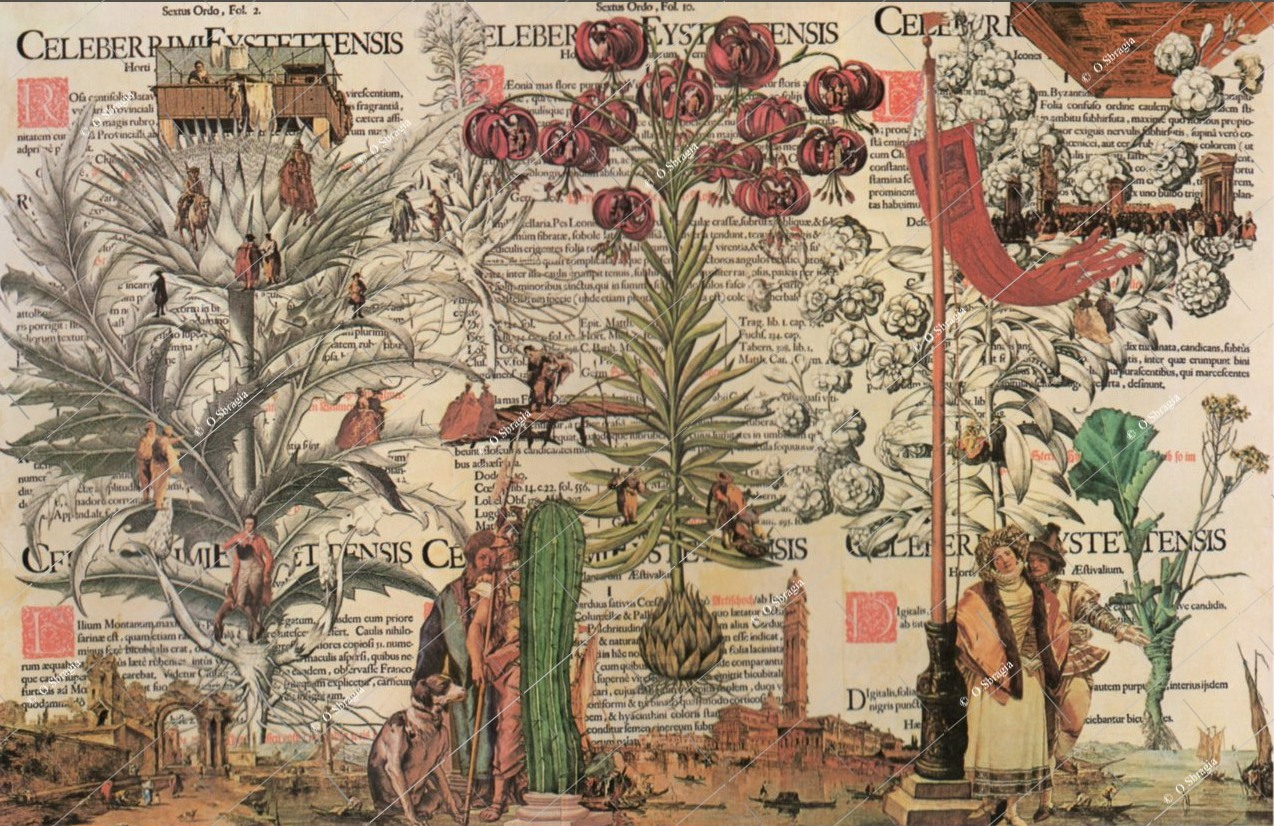

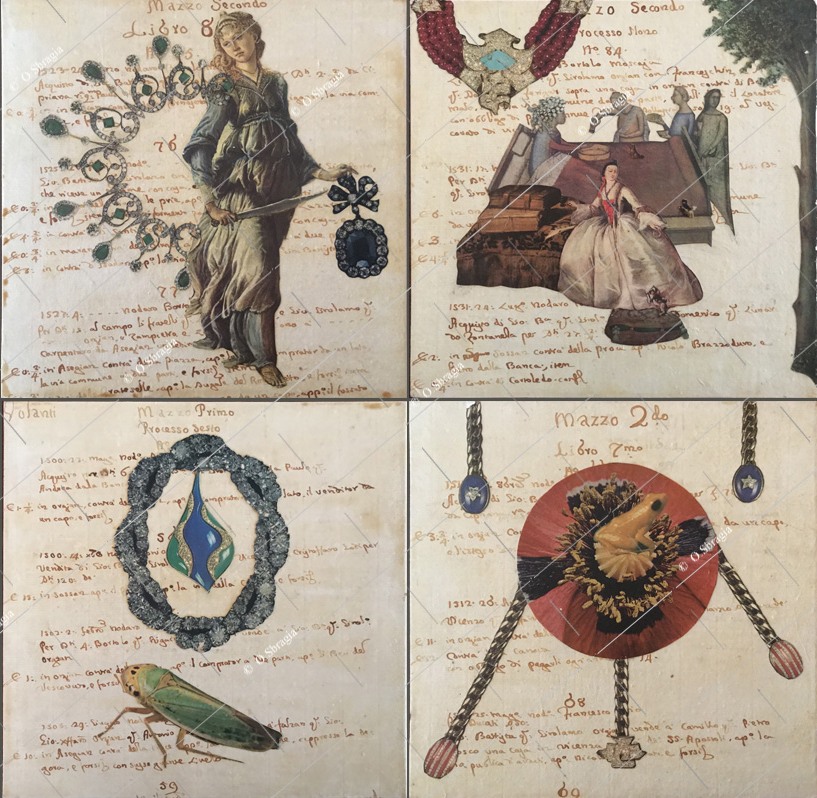

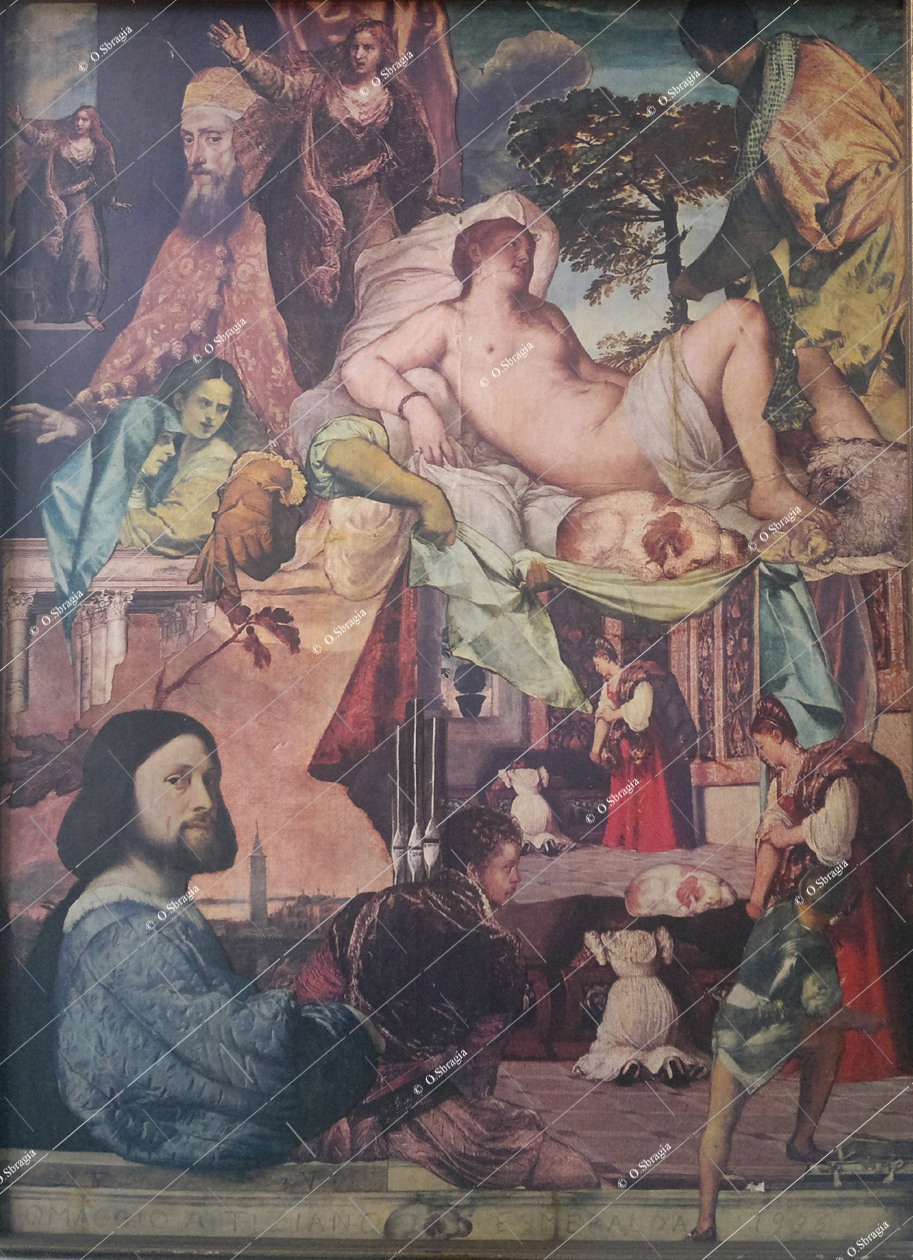

At the Sagittarius Gallery Esmeralda Sbragia Ruspoli is showing a series of original baroque collages that emerge from the elegant d

ecorative quality this type of minor art usually tends towards and reach the threshold of so-called surrealism. The intelligent and

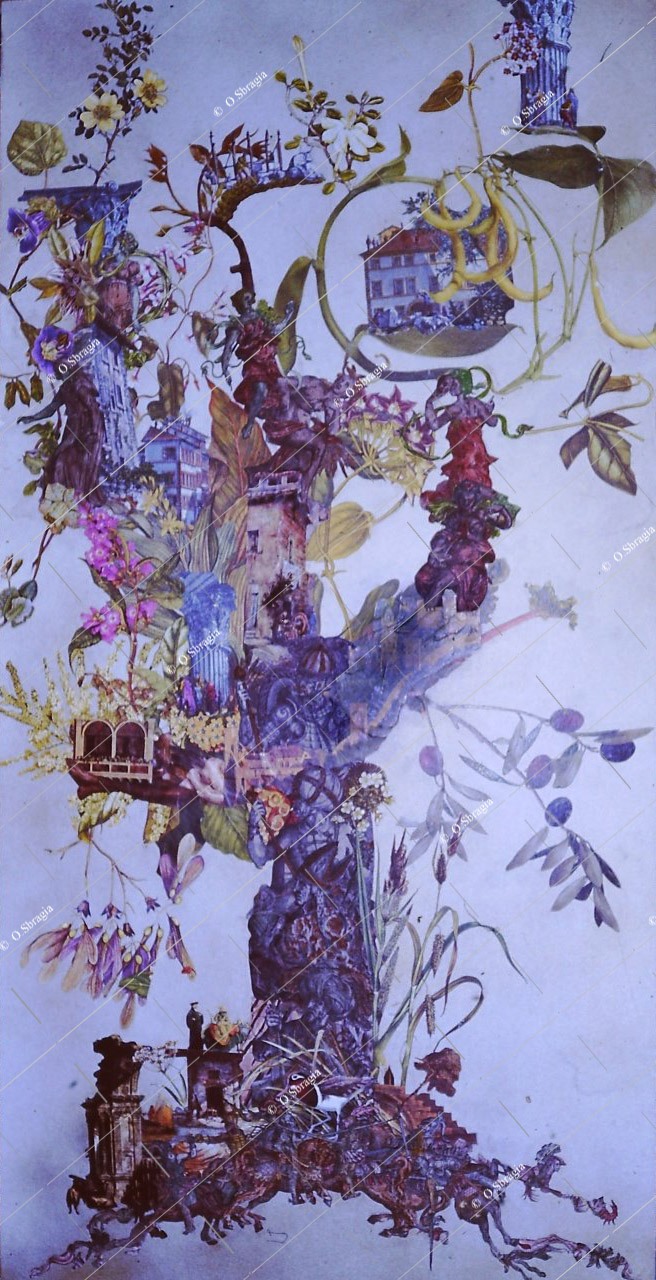

accomplished Esmeralda does not intervene with a single pencil or brushstroke of colour in the execution of these works of hers, which

she creates by cutting the most disparate images from old magazines, illustrated volumes, prints, anatomical, zoological, and botanical

tables, art books, etc. and then pastes into complex figurative aggregates, thereby creating new and bigger fantastic images.

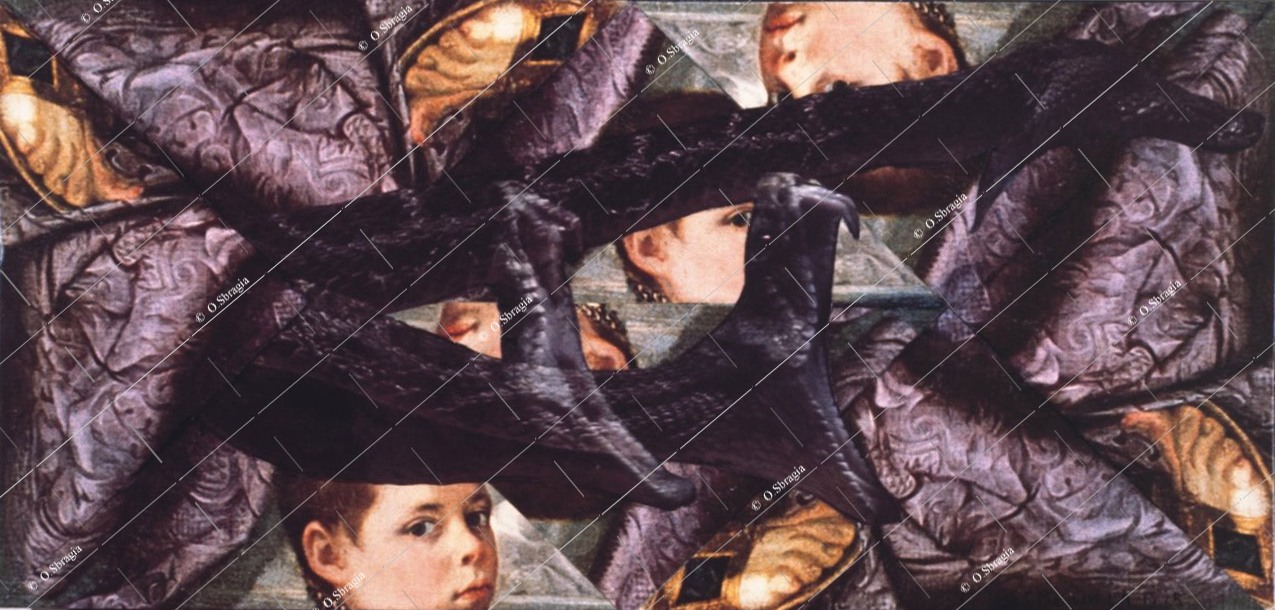

In these "collages'' - which seen from a certain distance are somewhat reminiscent of sixteenth-century trappings as well as

certain Chinese panels - Esmeralda Sbragia reveals - in addition to a singular ingenuity and an uncommon fantasy - distinct pictorial

qualities traceable both in the form of the image, harmony of colour and in the tones and volumes that she manages to achieve by matching

and combining thousands of pieces.

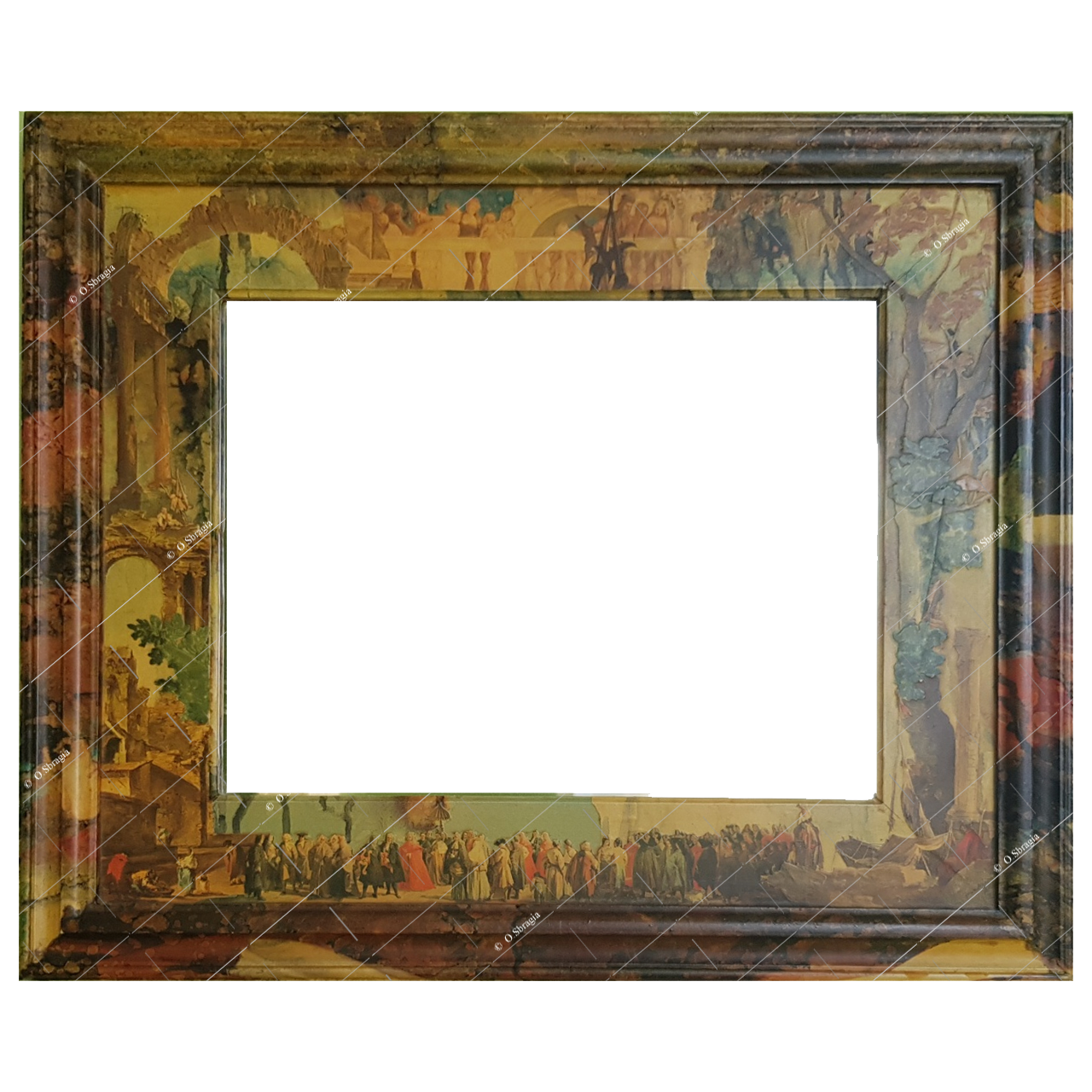

In our opinion, the best of this exhibition (keeping in mind, however, that they all require frames as well as additional space around them)

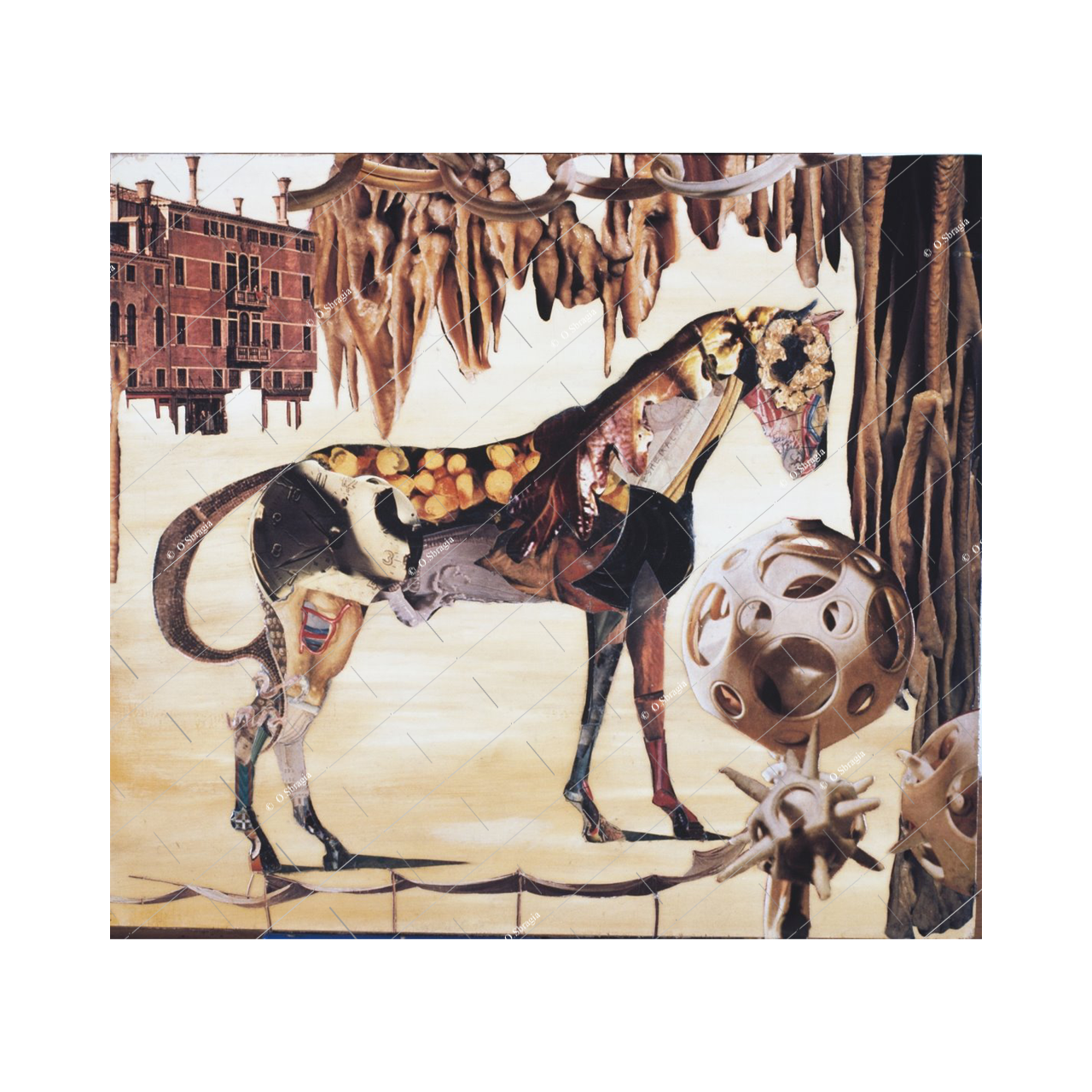

are "The Defeated Hero", "The Rooster", "Giraffe in the Sun", "Woman with Green Hair" and the "Mirror".

[hide the article]

Orio Vergani

Corriere dell'informazione, 9 October 1958

The Collages of Esmeralda: In the silent Parnassus of the Signora Ruspoli Sbragia Two Muses Preside: Scissors and Paste.

[read the article]

[hide the article]

At number 5 Via Sant'Andrea - an " old Milan" doorway - and it would not come as any surprise to see Tommaso Grossi or Rovani

step out or meet in the courtyard and a few steps away Ugo Foscolo lived - displayed on a handwritten card bearing a name that was dear

to Victor Hugo: Esmeralda. In the back of the courtyard are a couple of rooms: those of the Galleria dell'Ariete. A glass door separates

two worlds: one of the romantic Milan of 1858: our great-grandparents sighing over the romances of Lucrezia Borgia or Luisa

Miller - and that of the Milan of 1958, abstract, dodecaphonic, electronic, metaphysical.

The mother-of-pearl inlaid mandolin has been substituted by the unbreakable black long-playing record: the slow meticulous stitches of

crochet or bobbin lace by showy cretonnes: the 'gothic' armchairs dear to the noble Poldi Pezzoli by foam rubber armchairs coloured

tamarind pulp, robin redbreast and grapefruit rind. The floors are polished: barefoot maidens could dance there; the silence is soft: the

ticking of a wristwatch would ruin it. Scenes from a ballet, much more interesting that that of Sagan. Long-limbed women wearing flat shoes

enter, their eyes like Marie Laurencin, mouths like Gruau: their hair crowned by flowers. They enter and group in front of the paintings

exhibited on the walls. They are alive, these Anxious Muses of a metaphysical De Chirico who no longer needs to make statues with manikins

and instruments.

I said that they look at the paintings but in reality these are not paintings, they are collages: two unusual Muses preside in this silent

Parnassus: Scissors and Paste. Esmeralda - Esmeralda Ruspoli, wife of the actor Sbragia - does not pretend to have made a discovery. One

could have an amicable conversation about collages. In the eighteen-hundreds they were made with the pages of calligraphy albums, love letters

on pale blue paper, assignats of various revolutions, Flaxman prints. It is probable that they became popular again because of advertising

photomontages, which were, in vain, referred to as photo-mosaics. There was a return to prints, both coloured and not, extracts from eighteenth

century encyclopaedia, travel books, fashion journals. Collage is a humble art: it even makes use of inferior material like the figures of

magazine covers; it makes popular lithographs agree with those of zoology books: Venus and the Tapir, Diana and the Ornithorhynchus. Whereas

photomontage is the child of futurism, collage is the child of metaphysics: its oldest ancestor is Arcimboldo with his marquetry portraits of

carrots, onions, and plums: its closest inspiration comes from De Chirico. Cocteau, Max Ernst, Dadaism and Surrealism; the languor of oneiric

arte, encounters with Salvador Dali and with Tanguy, languid amalgams and eccentric dreams.

Esmeralda began to "paste" in her mother's villa of Maser in face-to-face contact with the frescoes of Paolo Veronese. She is not the

only Italian collagiste: one need only recall the Roman Lida Mastrocinque and the Milanese Titina Rota. She must have been surrounded

by masses of old prints like certain Neapolitan collectors who lived amid thousands of matchboxes using their nineteenth-century vignettes to

make lampshades, screens, fire-screens, and trays. Esmeralda also had precise applications in mind: she started by decorating the doors of the

house, then those of certain armoires, just for fun. That of collage is a gentle vice; a minor intoxication that becomes an addiction; a way to

wander silently, while remaining seated, scissors in hand.

Elegant taste, her hand a bizarre guide and her paste-brush. Hermeticism and surrealism by now are consanguineous. Technically, all the pieces

are admirable: her patience must be boundless.

Many are also functionally beautiful, like a cornice on a red background, a curtain with broad stripes and zoological motifs, and certain enamelled

trays. Others are purely decorative, their only function, like a beautiful "rooster", to open dreamlike paths onto a wall. It is understandable why

Dino Buzzati liked these pages and presents them with a very fine preface. That of collage is a kind of sect; whoever tries it once is never again

free, like smoking opium. When he was rehabilitating from the use of opium, Cocteau tried it by cutting up old anatomical charts instead of poisoning

himself. I am convinced Paolo Veronese would have no objections to the subtleties of tones created by these encounters of old prints in the villa of

Maser. And I think that choreographers and set designers entrusted with certain themes like The Sorcerer's Apprentice and La boutique

fantasque would have a great deal to learn from these motifs.

[hide the article]

V.G.

Il Tempo, 4 February 1957

Roman Exhibitions

[read the article]

[hide the article]

How many times have we written that Surrealism has made its way into high society, which has always loved the quirks (as literature, content),

the tradition and the beautiful and canonical manners (like a formal tradition)? Again, an example in the collages of Esmeralda Sbragia

Ruspoli at the "Sagittarius". Nothing better could be desired from such an Arcimbolesque genre. The "artist" creates a refined elegance; she

invents extravagant personages, figurines and masks of an impossible theatre. A fashionable fantasist, she has a sure hand; these cut out figures

of hers are composed with beautiful brio, their colours harmonising with exquisite taste. Fortunately hers is an ironical imagination, paradoxical

but not morbid. Salvatore Dalý with his complexes is not the direct inspiration of such admirable creatures. Panels therefore for a salon, a fashion

atelier; motifs for tasteful (and disturbing so to say) screens. Luxury craftsmanship.

[hide the article]

Lorenza Trucchi

La fiera letteraria, 18 February 1957

Sbragia Ruspoli at the Sagittarius Gallery

[read the article]

[hide the article]

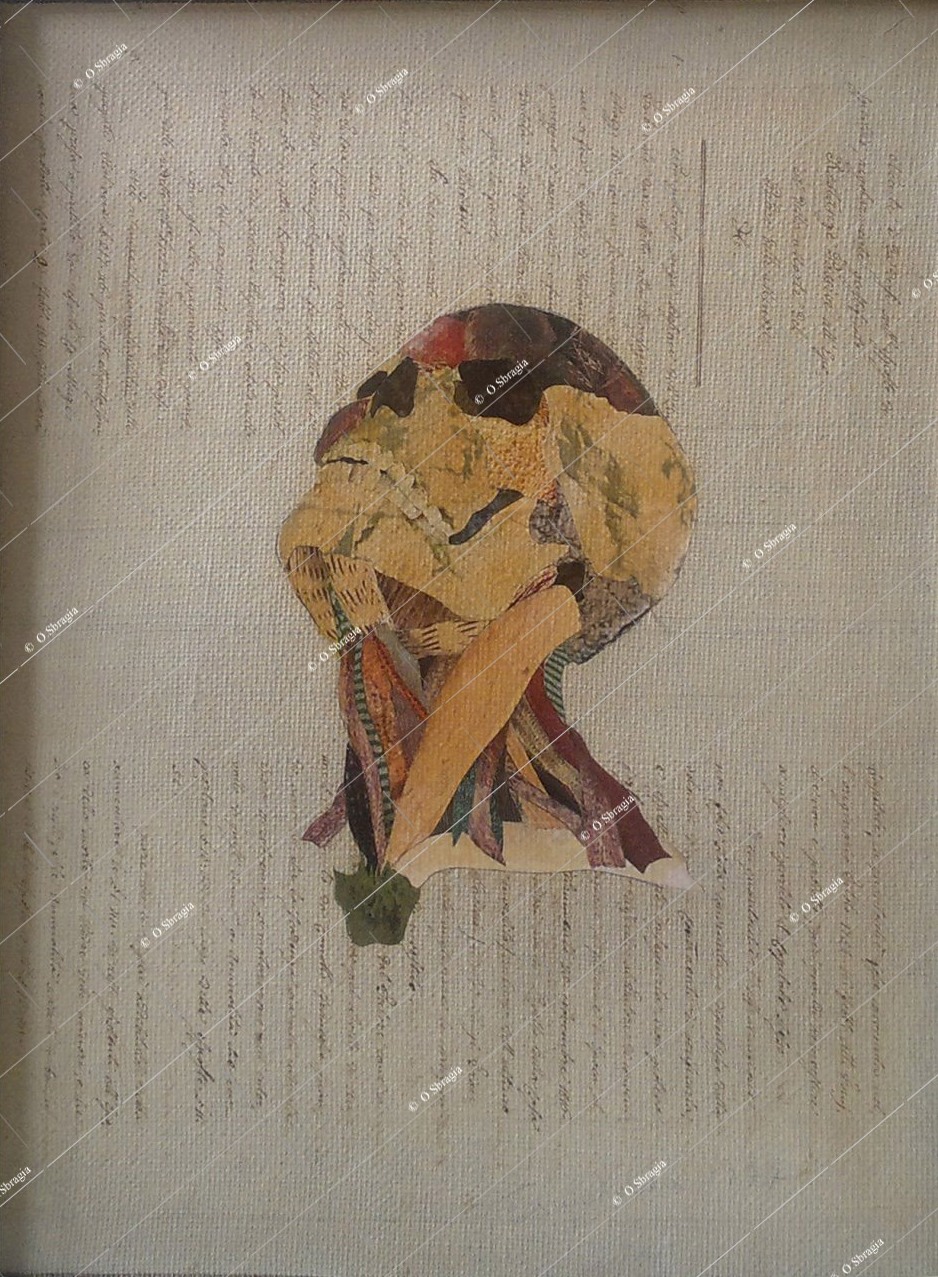

The collages that Esmeralda Sbragia Ruspoli is showing at the Sagittarius Gallery are among the best and most accomplished

that can be admired in that field. Esmeralda has ransacked 'years' of old magazines and entire collections of ancient and precious

prints to create these singular compositions. In such cases, collage almost always results in a mundane surrealism that is more or less

perturbing or in an intellectualistic satire of facile effect. Esmeralda, instead, adopts heterogeneous material for pictorial use:

that is, she uses the most absurd and craziest images like the tiles of a mosaic that notwithstanding its inevitable, refined decorative

eccentricity is, however, constructed with a felicitous pictorial sense.

One sees how the variegated and imposing "Rooster"

composed of a hundred varied ingredients - women, soldiers, fish, shinbones, masks, arms - has a plastic and chromatic emphasis. No perverse

or faded witchcraft in these collages, executed with a meticulous technique and confident judgment; but, rather, a series of festive if not

light-hearted evasions that Esmeralda permits each one to participate in with the fantasy of a finite yet unconsumed childhood.

[hide the article]

Armando Stefani

La Nazione, 27 August I957

Pictures painted with scissors. The works of Esmeralda Sbragia of Rome are the latest figurative news of Rome. The godsend of used book sellers

[read the article]

[hide the article]

Rome,

The latest artistic news from Rome is neither a painter nor a sculptor. There are many ways to follow one's soul and the one currently being talked

about in the capital has to do with scissors. It has to do with collages: a particular kind of collage. The technique of composing a picture with cut-out

pieces of paper is not new; what is new is that it is not being used by an artist as a curious and artisanal sub-product; it is instead the central theme

and, for the moment, the only theme of inspiration.

We wish to talk about it precisely because these works, besides being aesthetically very significant, represent a key for understanding certain anxieties

of the time; they are indicative of some aspects of Italian society and have a worldly taste that for once is neither frivolous nor banal. I shall explain

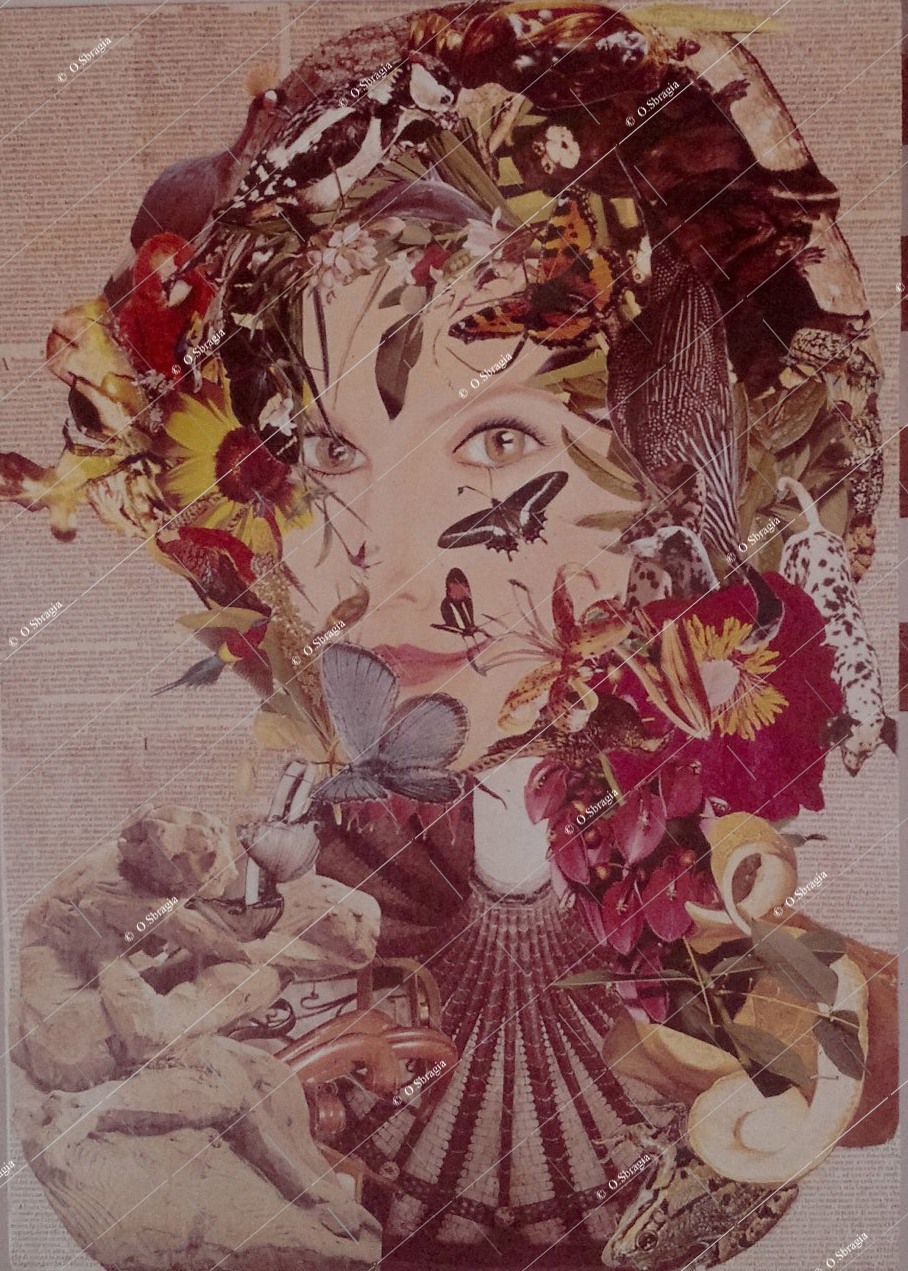

what they are like. Imagine a drawing of a rather common subject: a woman, a flower or a house. One made up of countless cut outs from newspapers, prints,

figures, maps, book illustrations; in brief, all kinds of figures. The choice of these figures is an expressive counterpoint of the overall subject; a

counterpoint that is apparently only automatic and obligatory. Out of the vast ocean of printed papers, Esmeralda Sbragia Ruspoli fishes the allusive,

ironic, tragic, significant 'piece'. Her first exhibition, presented by Dino Buzzati, is of great interest.

It lies midway between a nineteenth-century world of distinct and definite opinions and customs and the more dangerous temptations of modern times. The

depictions of that society of the last century in which many today see a kind of lost paradise and in general the images of all epochs are decomposed,

atomized, dissected and then compartmentalized into a mosaic of hallucinating immobility and fragility in a kind of equilibrium that could break from

one moment to the next.

Now entering European and American collections, these collages display the cold analytical intelligence of upper-class society together with a despairing

and amazing nostalgia of the blood aristocracy and the surgical and somewhat mysterious penetration of today's culture. The author is all of these things:

granddaughter of the great financier Count Volpi, daughter of a Ruspoli (it is curious how often this name has been reappearing recently, from the heroism

of the brothers who died in Africa to the snobbism of Dado, the unscrupulousness of others, and lastly, now, this artist, the symbol of many contradictions),

wife of one of the leading actors of our time, who has just been seen in a brilliant interpretation of the complicated key figure of the posthumous drama

of O'Neill. In the Palladium villa frescoed by Veronese at Maser, Esmeralda one day found the only door that the Venetian painter, his disciples and the

others who had participated in the decoration of the building had left untouched. There she attached pieces of paper tastefully, perhaps to please her

mother who owned the building, and to leave some trace of her childish dreams. She has since become the boon of Roman used booksellers, and in a space

that her three children have left free for her in their apartment she destroys pages and pages with her scissors and a nail file, piling them up in big

boxes, and then taking out ones good for pasting onto a canvas: foxhunts rotate round the blank eye of a Greek statue, a series of porticos becomes a

female abdomen, the pages of a drawing manual are transformed into tresses ruffled by the wind.

[hide the article]

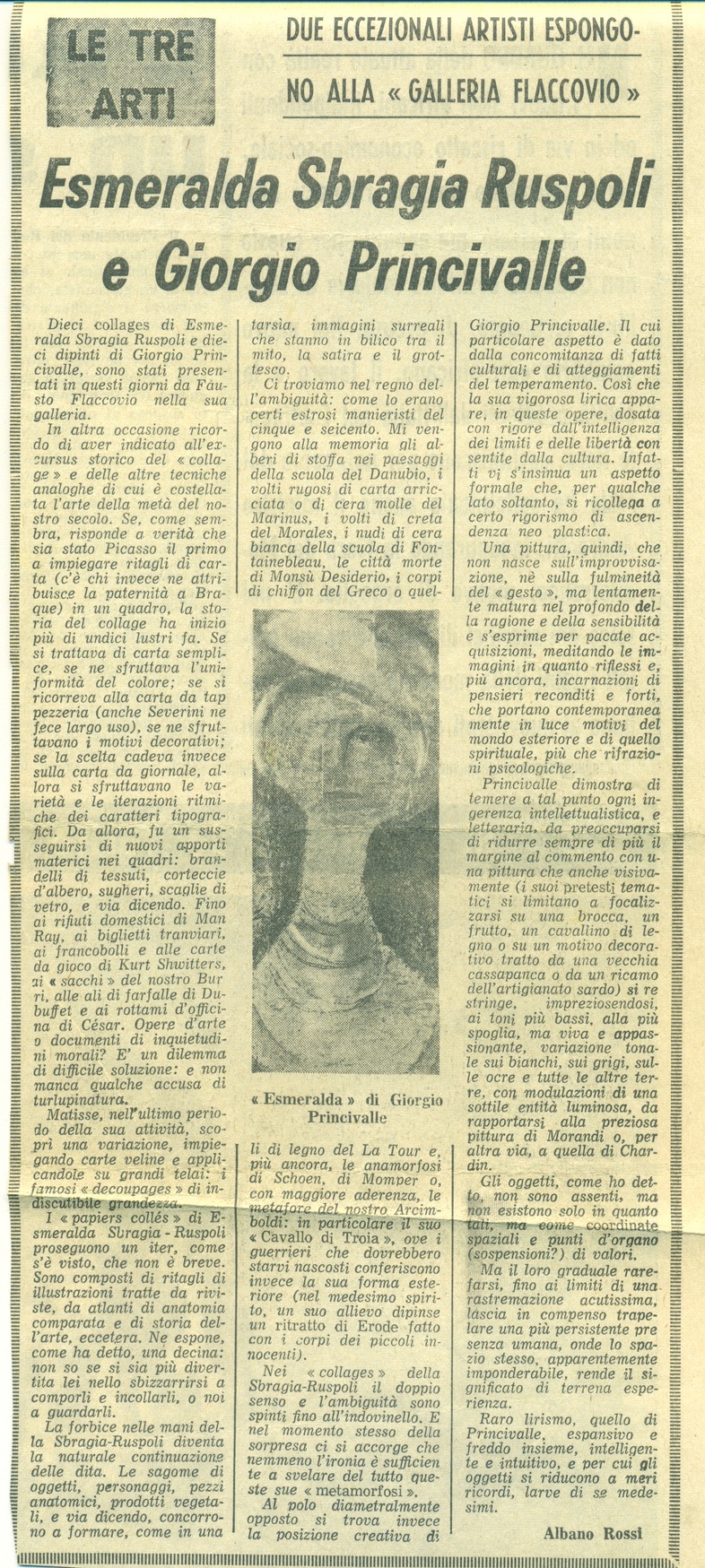

Albano Rossi

Palermo, 1966

Esmeralda Sbragia Ruspoli and Giorgio Princivalle

[read the article]

[hide the article]

Ten collages of Esmeralda Sbragia Ruspoli and ten paintings of Giorgio Princivalle are currently being shown by Fausto Flaccovio in his gallery.

On another occasion, I remember having indicated the historical excursus of the collage and other analogous techniques characterising mid-twentieth

century art. While it seems that Picasso was the first to start using pieces of cut-up paper (there are those who attribute this paternity to Braque)

in a painting, the history of collage had its beginning almost sixty years ago. The uniformity of colour was made the most of when it was a matter of

standard paper; however, when it had to do with wallpaper (which Severini also used freely), then its decorative motifs were exploited; and if the

choice instead fell on newspaper, then the variety and rhythmic repetition of the typographical characters were utilised. After that a succession of

new materials were introduced into paintings: from cloth tatters, tree bark, glass shards, etc. up to the rubbish of Man Ray, the tram tickets, stamps,

and playing cards of Kurt Schwitters, the sacks of our Burri, the butterfly wings of Dubuffet and the scrap heaps of CÚsar.

Works of art or documents of moral anxiety? It is a dilemma with a difficult solution: and there have been accusations of cheating.

Matisse, during his last years of activity, came up with a variation using copy paper and applying it onto huge canvases: his famous "decoupages" of

indisputable greatness.

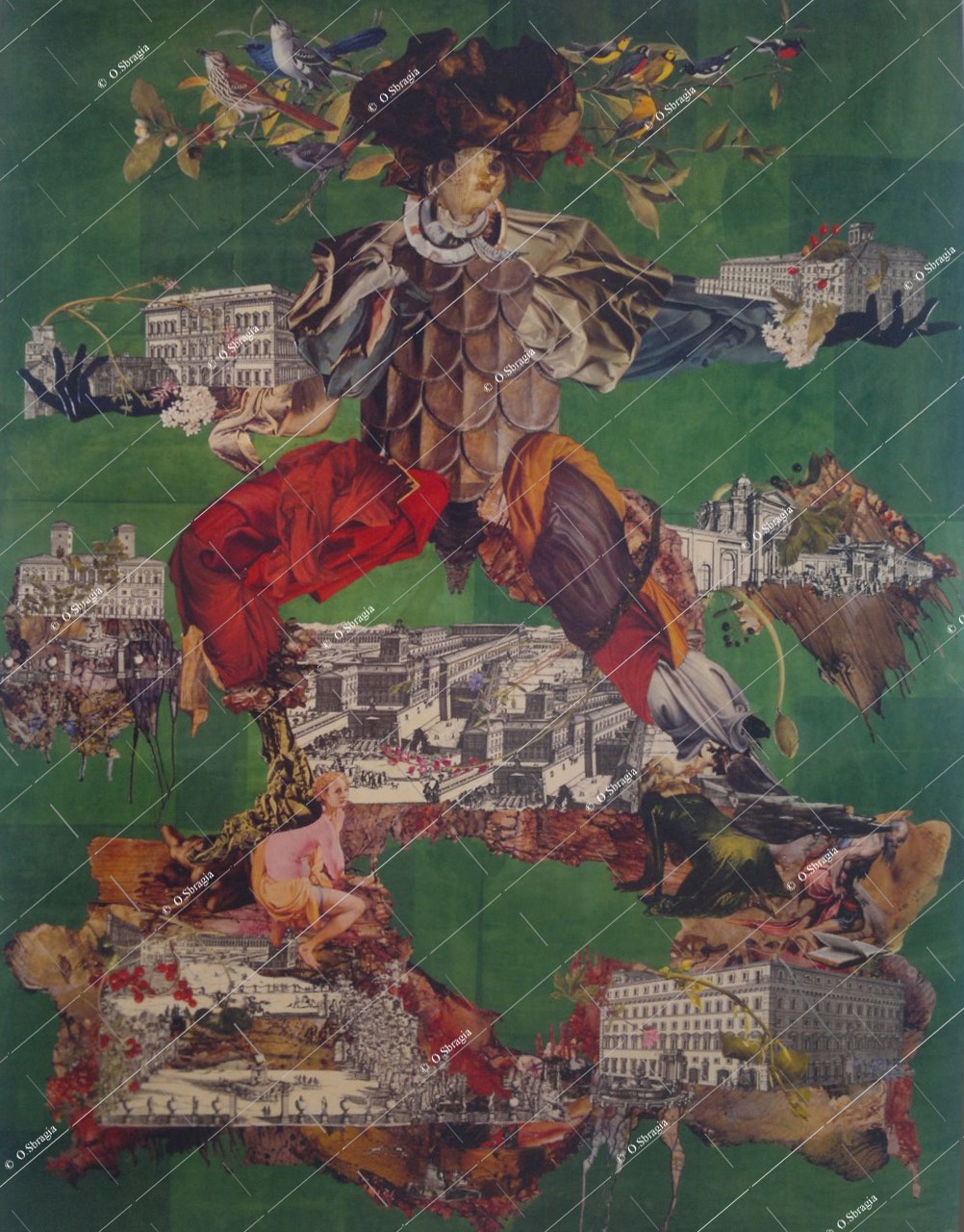

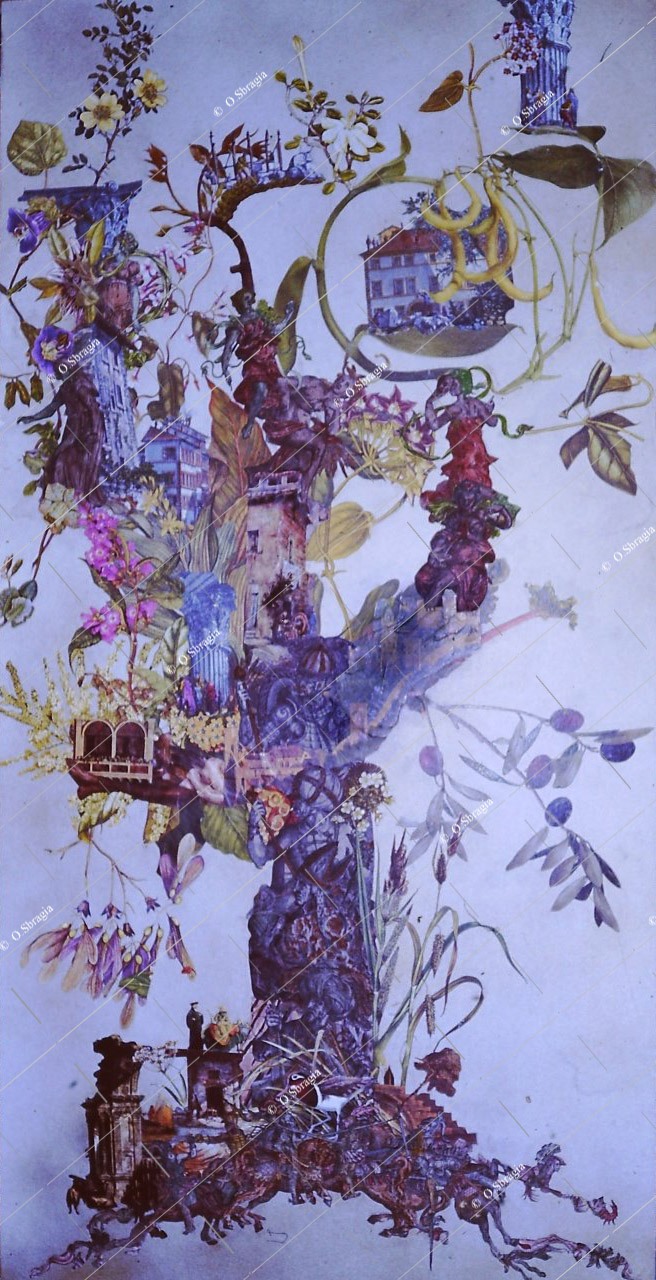

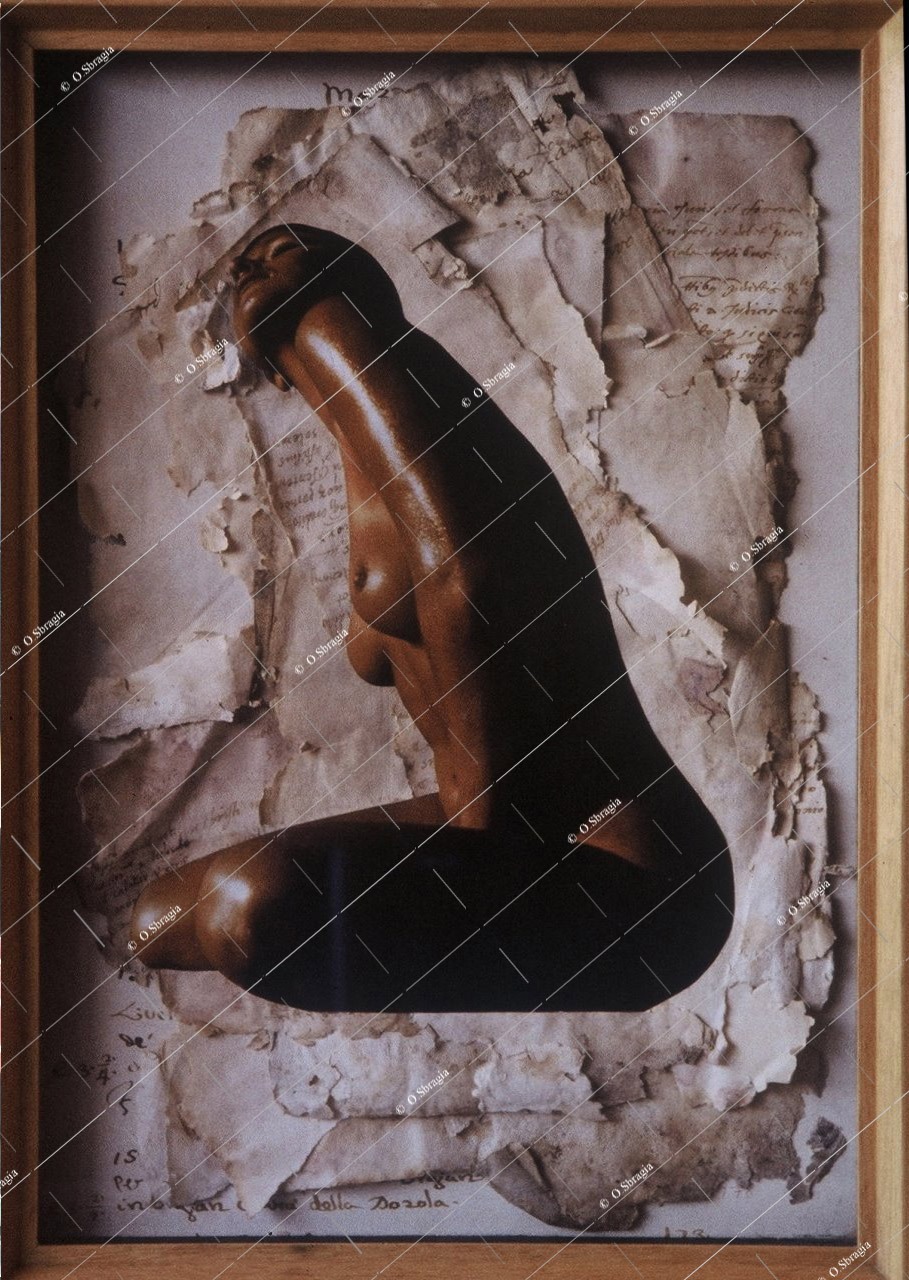

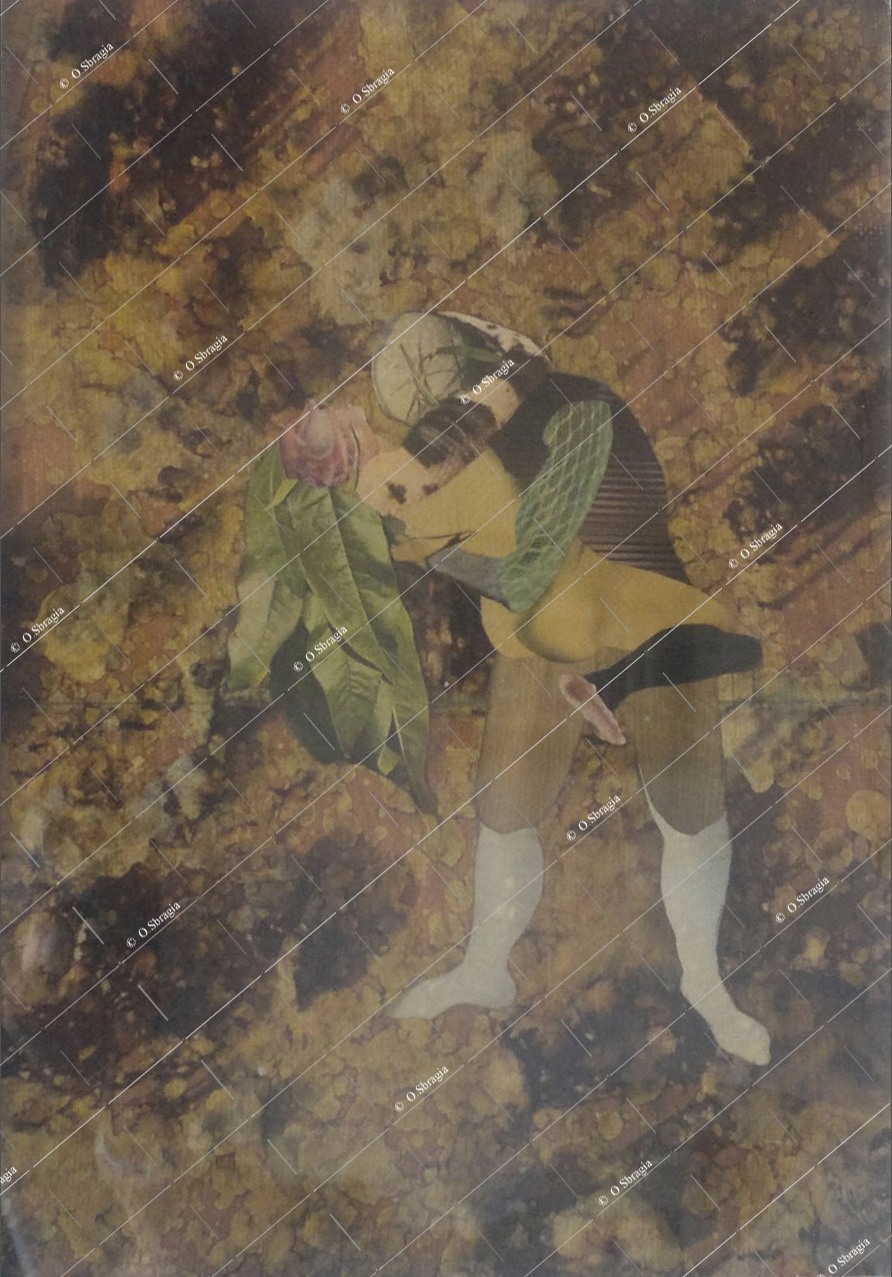

The "papiers collÚ" of Esmeralda Sbragia-Ruspoli follow a procedure that, as has been seen, is not brief. They are composed of cuttings of

illustrations taken from magazines, charts of comparative anatomy and histories of art, etc. She is showing some ten of these here, and I don't know

who has more fun: the artist who created them or the observer who looks at them.

Scissors in the hands of Sbragia-Ruspoli become a natural continuation of her fingers. The outlines of the objects, personages, anatomical pieces,

vegetables, etc. combine to form, as in marquetry, surreal images that hover between myth, satire and the grotesque.

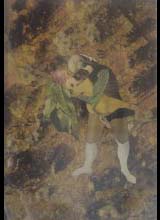

We find ourselves in the reign of ambiguity: as did certain fanciful sixteenth and seventeenth century mannerists who come to mind. The cloth trees

in the landscapes of the Danube School, the wrinkled faces of curled up paper or those of soft wax of Marinus, the clay faces of Morales, the nudes

of white wax of the School of Fontainebleau, the dead city of Mons¨ Desiderio, the chiffon bodies of El Greco or the wooden ones of La Tour as well

as the distortions of Schoen, Momper or, even more, the creations of our Arcimboldo: in particular his "Trojan Horse", where the warriors who

should remain hidden inside give shape to its exterior form (in the same spirit, a student of his painted a portrait of Herod made with the bodies of

the innocent babes).

In the collages of Sbragia-Ruspoli double meaning and ambiguity are pushed towards the enigma. And at the very moment of surprise, one realises that

not even irony suffices to reveal all the transformations [.].

[hide the article]

Vittorio Sgarbi

Catalogo Esmeralda, 1984

Esmeralda's Scissors

[read the article]

[hide the article]

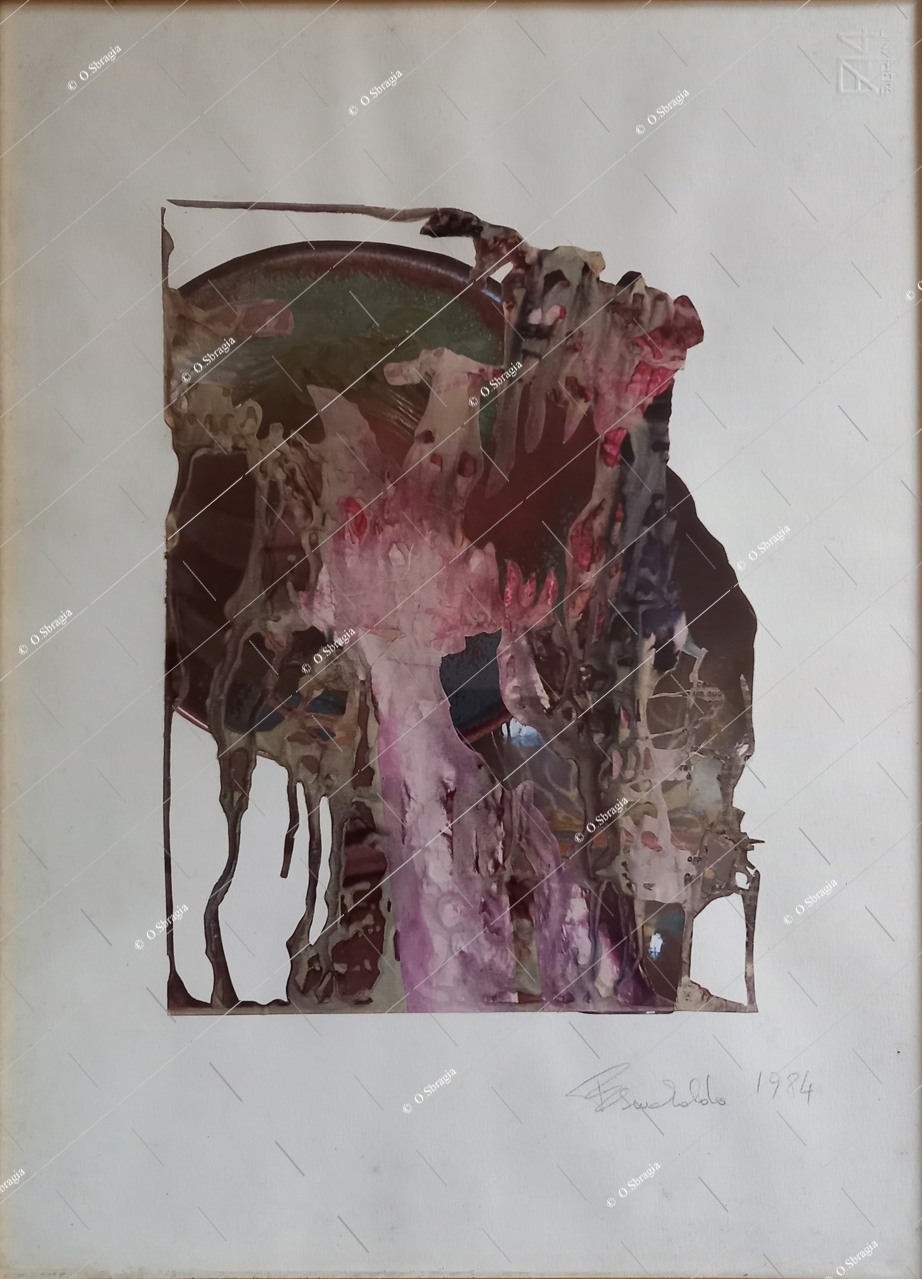

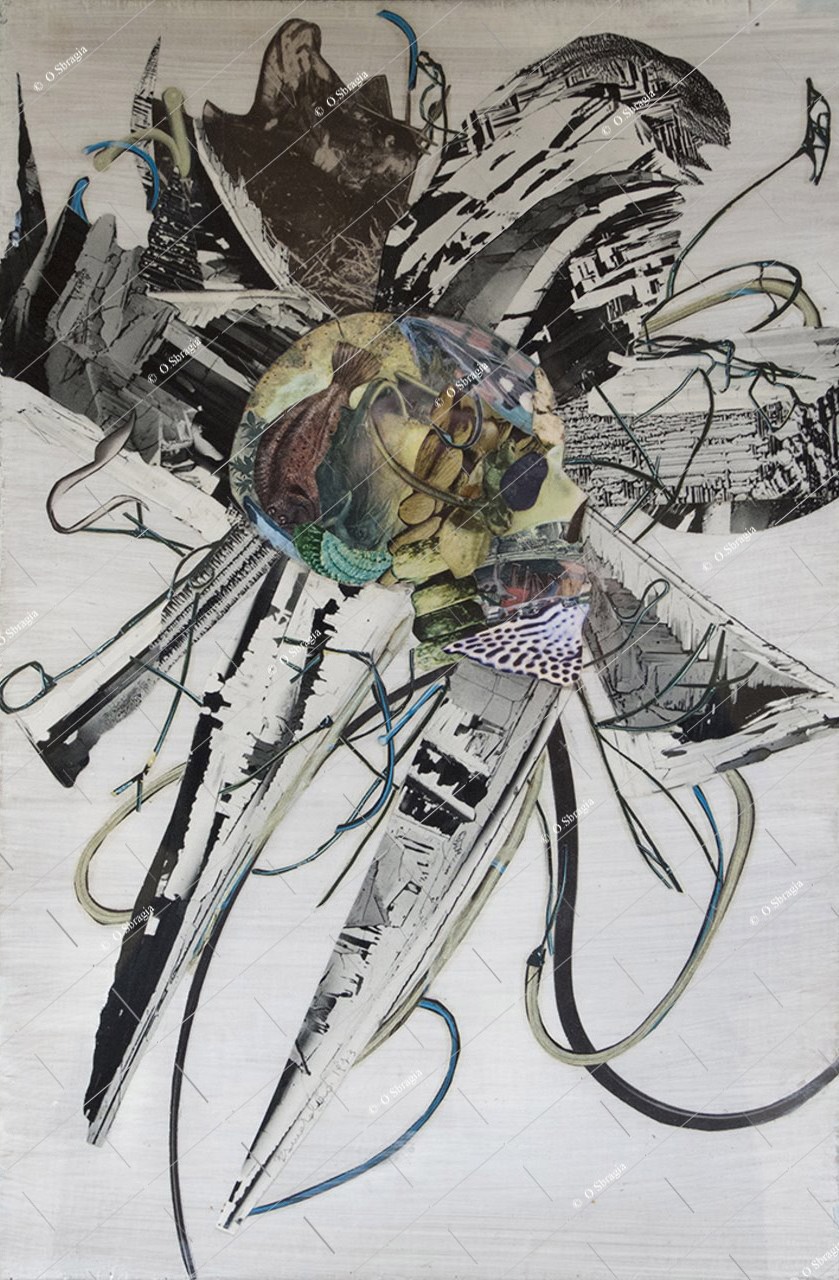

The world runs on two parallels for Esmeralda Ruspoli. On one are everyday objects, chairs, tables, plates, knick-knacks; on the other,

the same things merged into the fanciful and memory filled vision of Esmeralda's past. Just seeing her is to note a sign of distinction

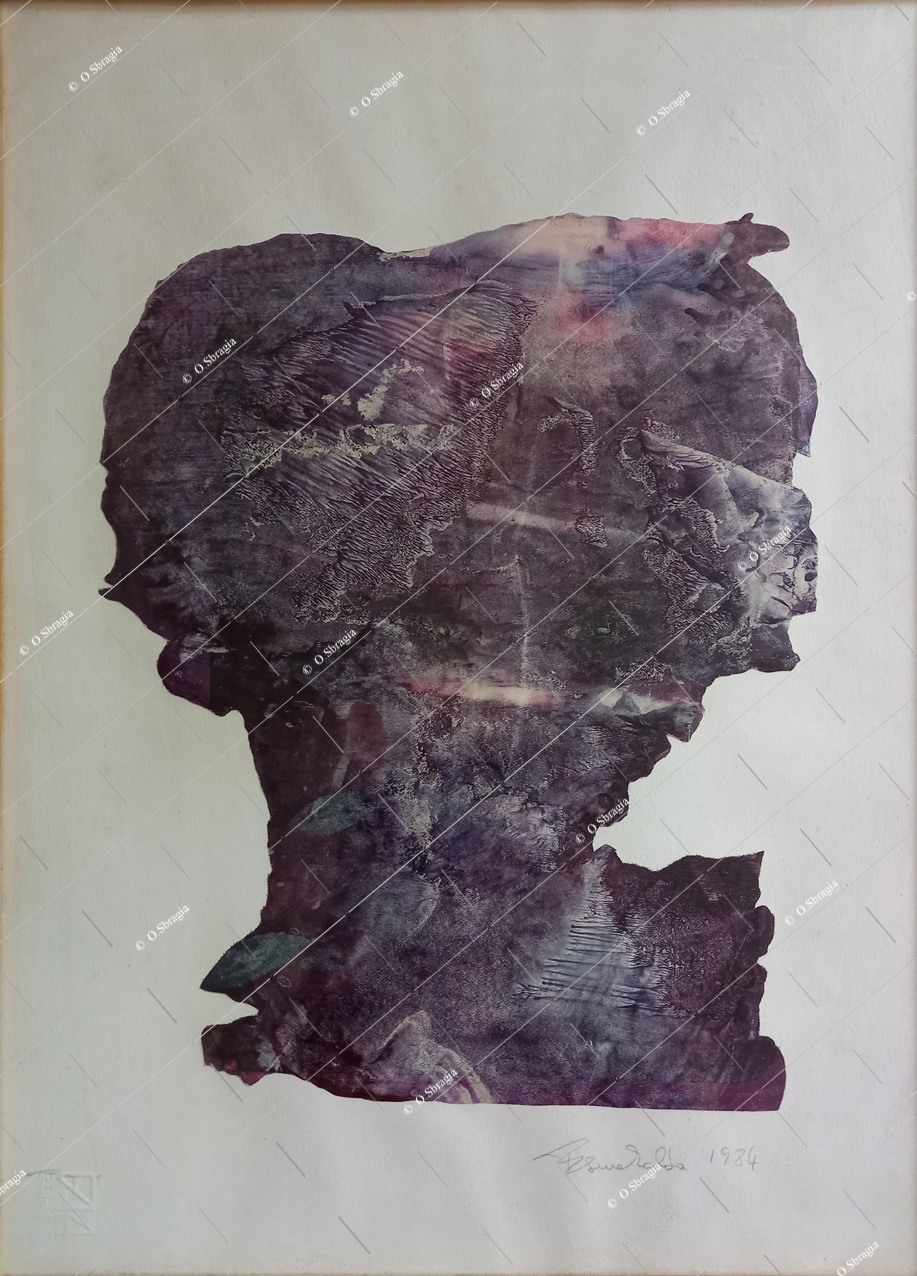

that makes her stand out from all those around her: the beautiful face crowned by a precocious white mane like the feathers of a rare

animal, the style of clothes that are always rather unusual and extravagant, the dreamy look, the tiny dogs. And all without artifice,

as if she too belonged to a parallel world that shares only a few events with our own. But her vision also wishes to be active and not

simply an unexpressed personal event. And so Esmeralda has created her own personal laboratory in a small room transforming objects, or

better yet, their surfaces. They sit timidly, undefended, undressed, as they are in nature. She attends them patiently with the slightly

mad, slightly perverse look of one who is preparing "a party" for them. Devious, then, because she has in the meantime prearranged this

encounter with huge scissors in order to cut up newspapers, magazines and books where some beautiful images have attracted her eye. And

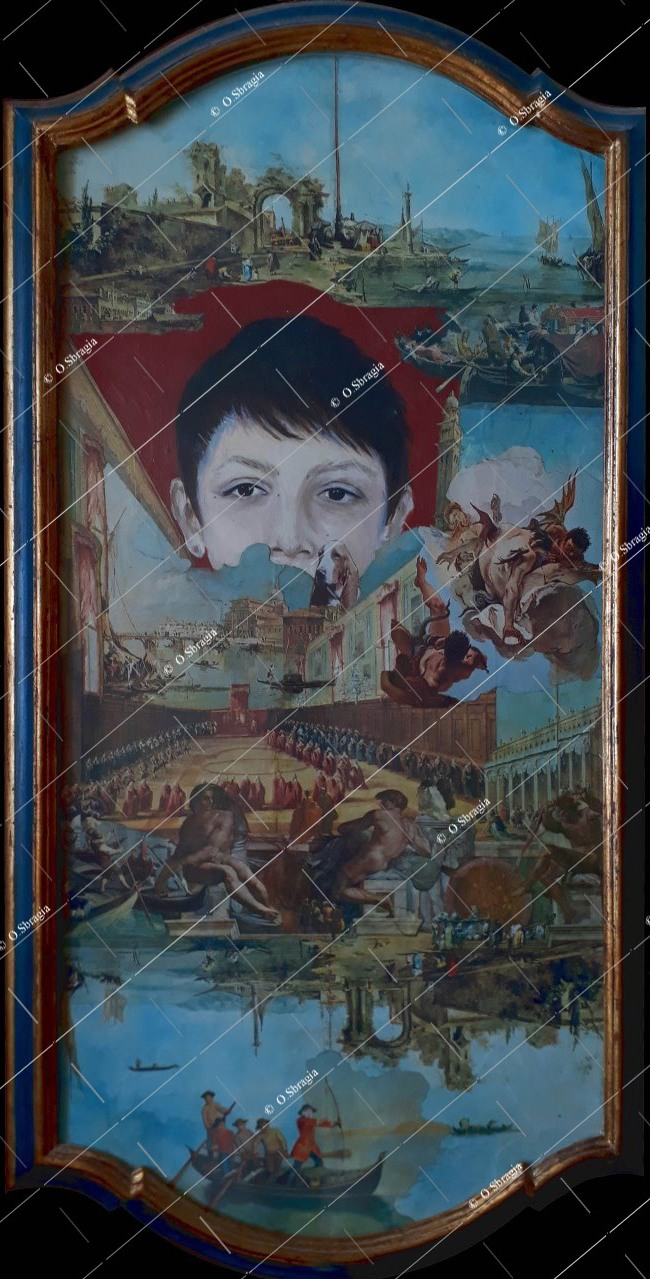

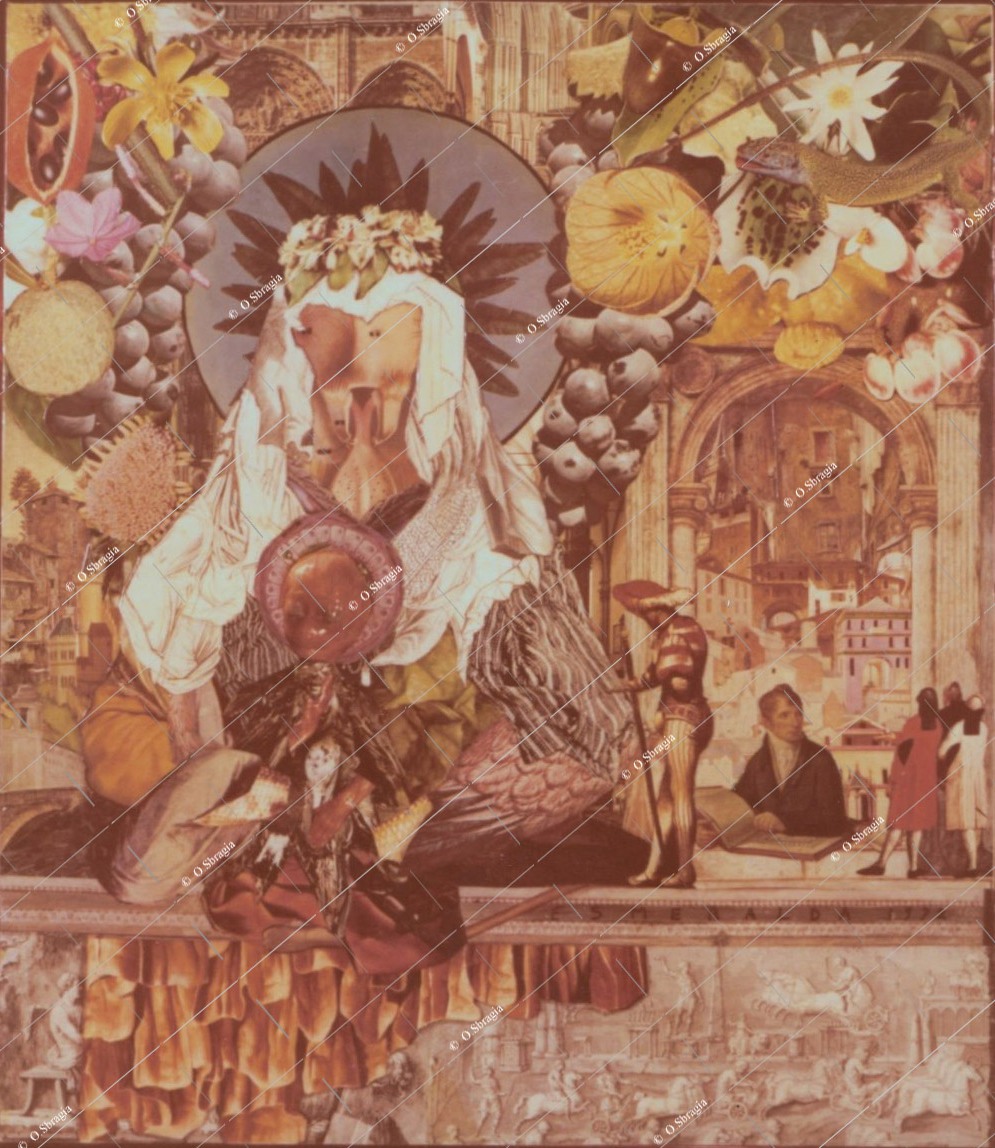

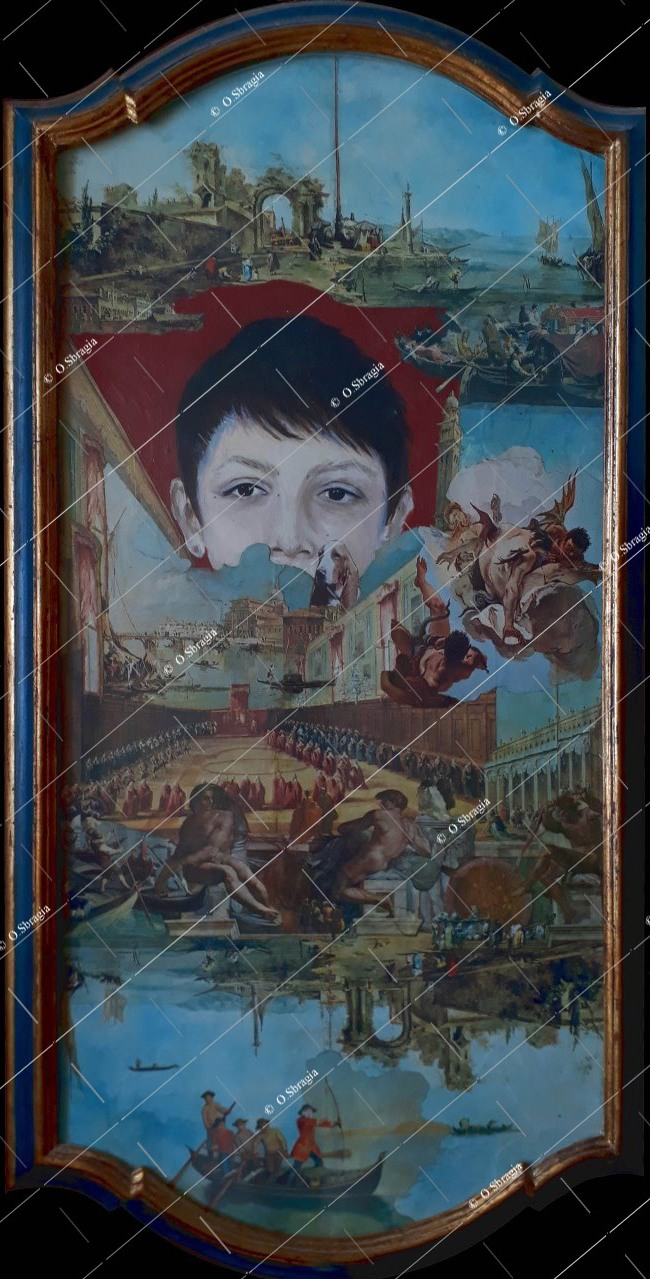

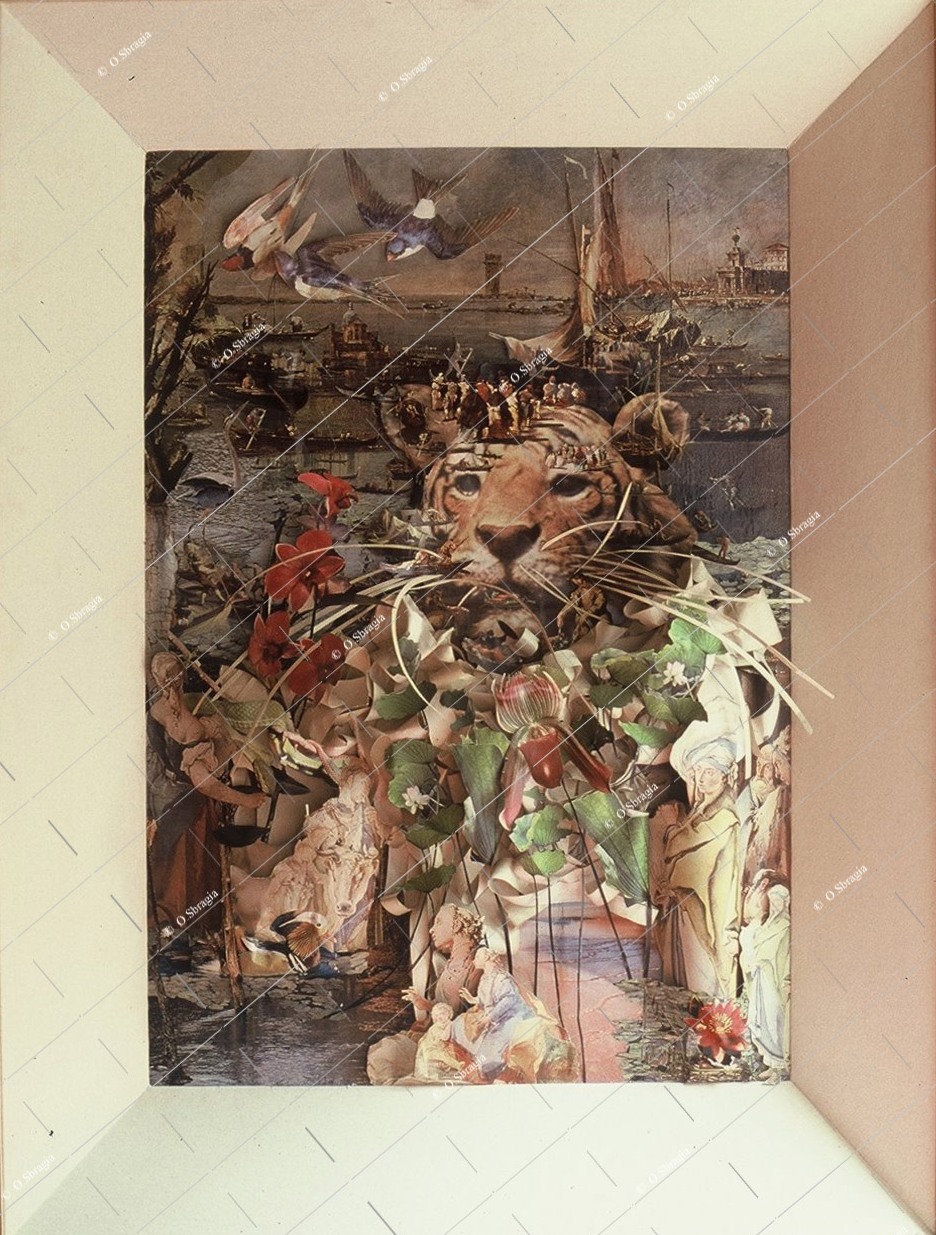

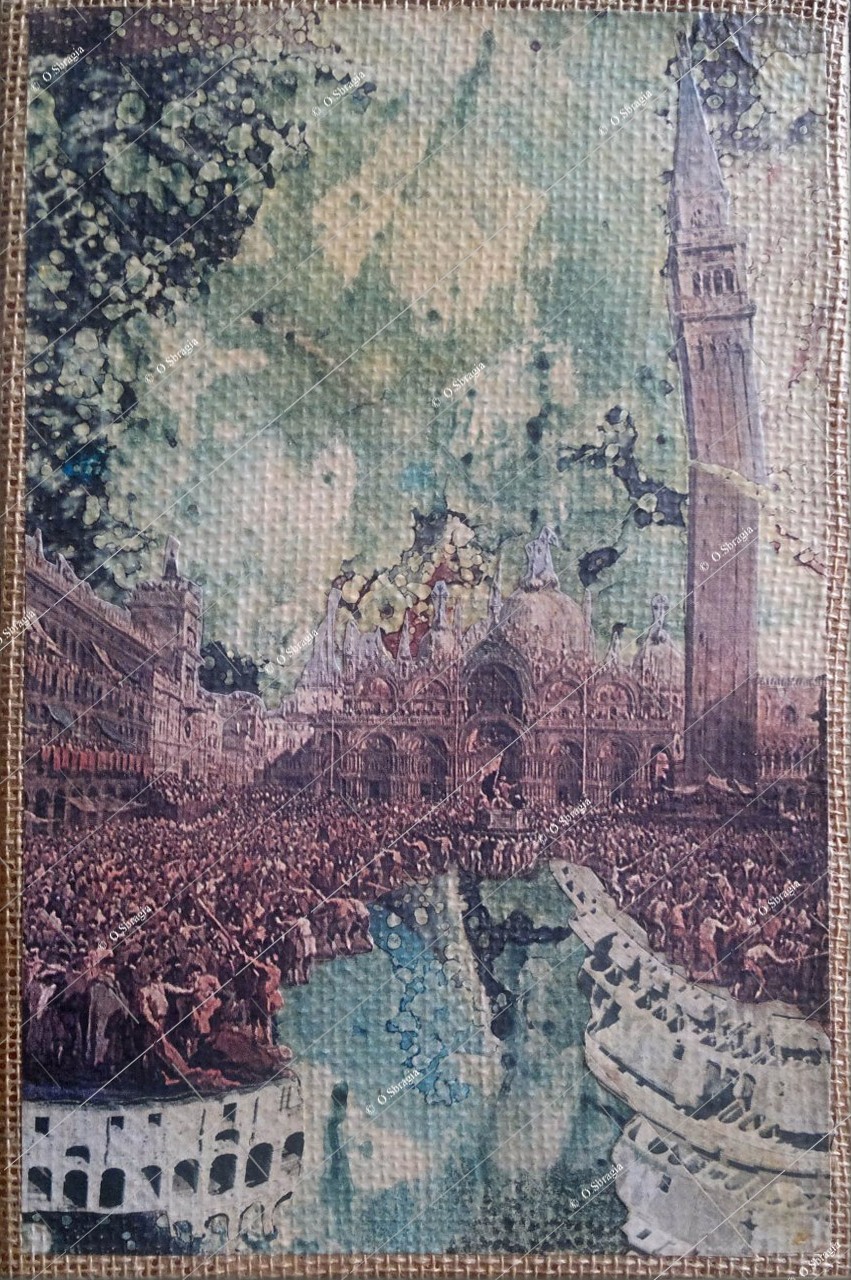

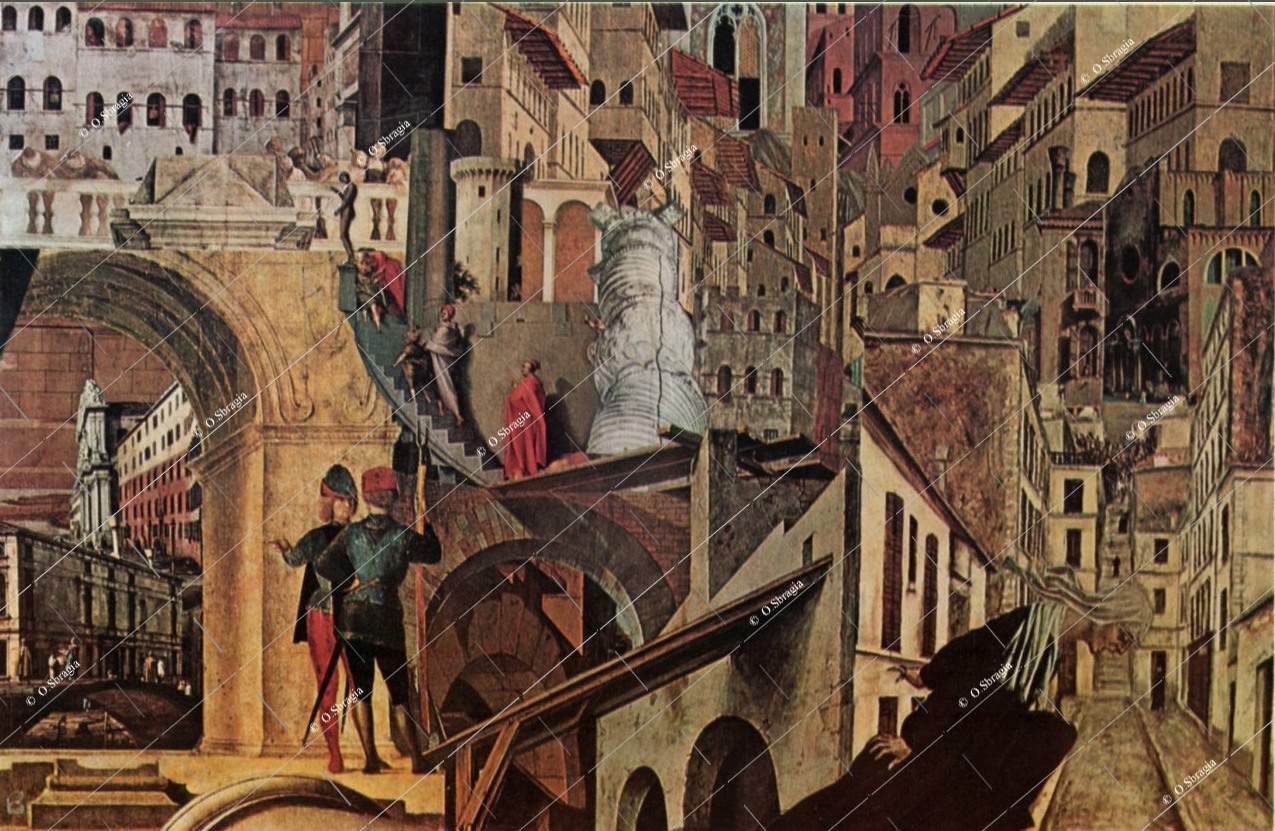

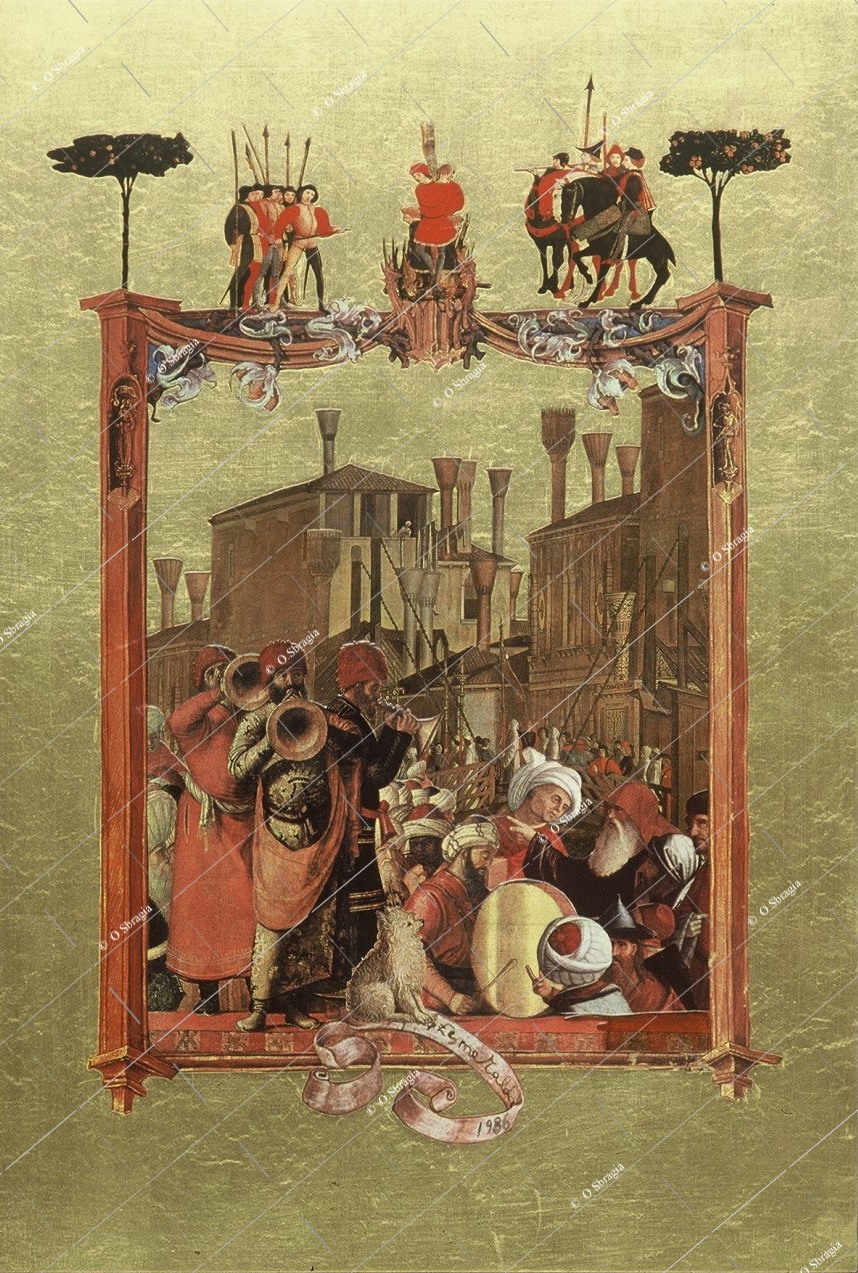

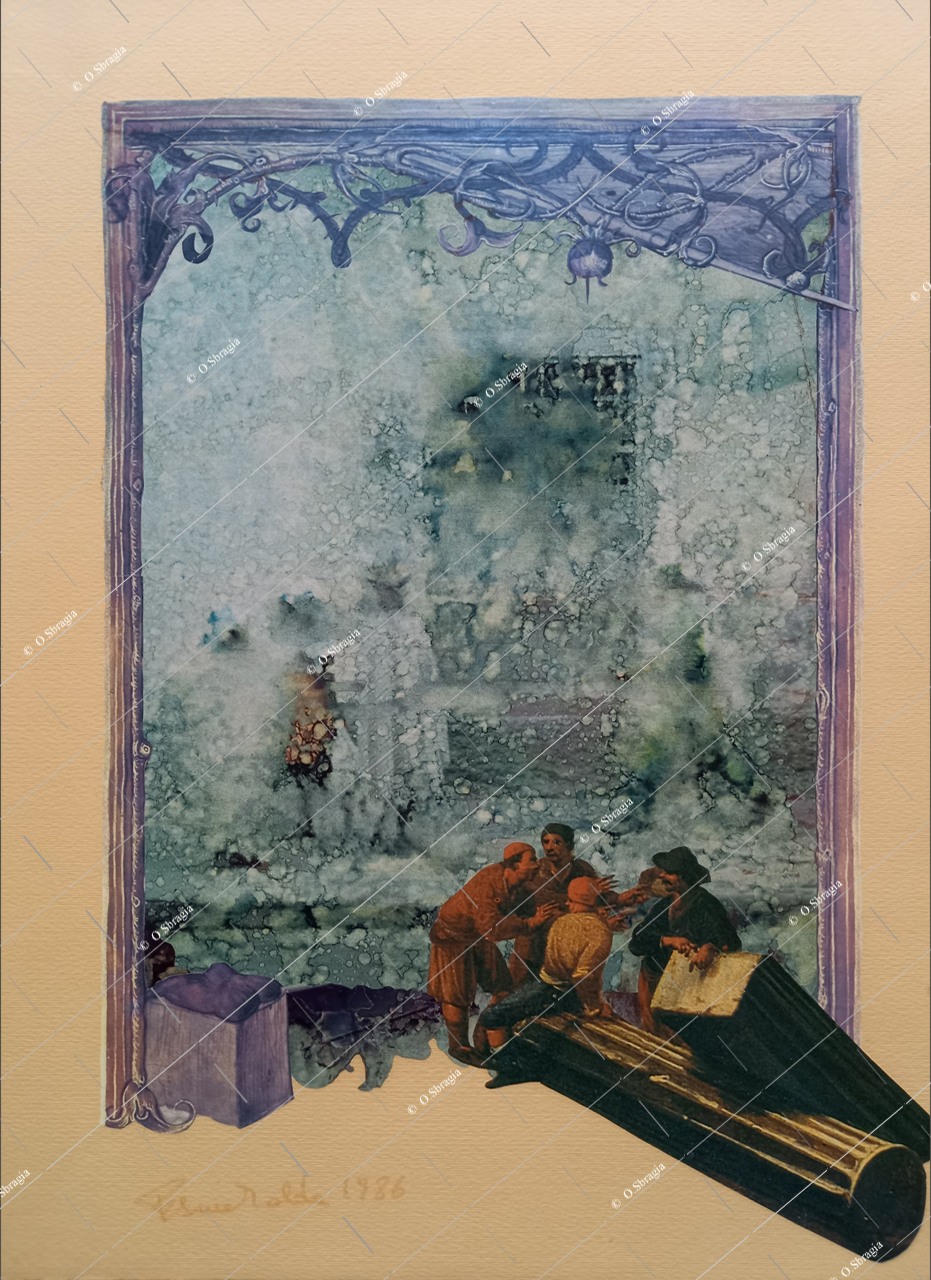

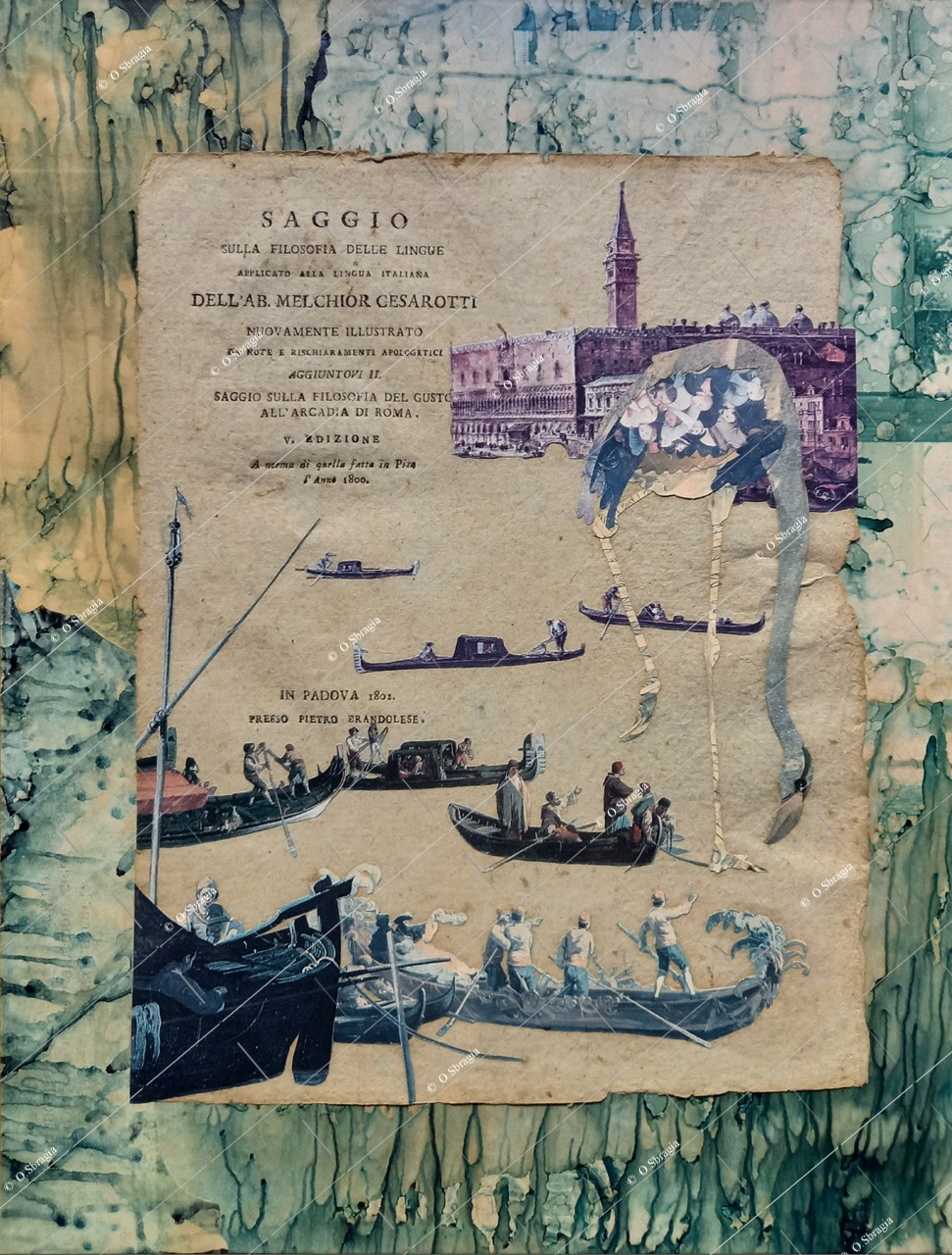

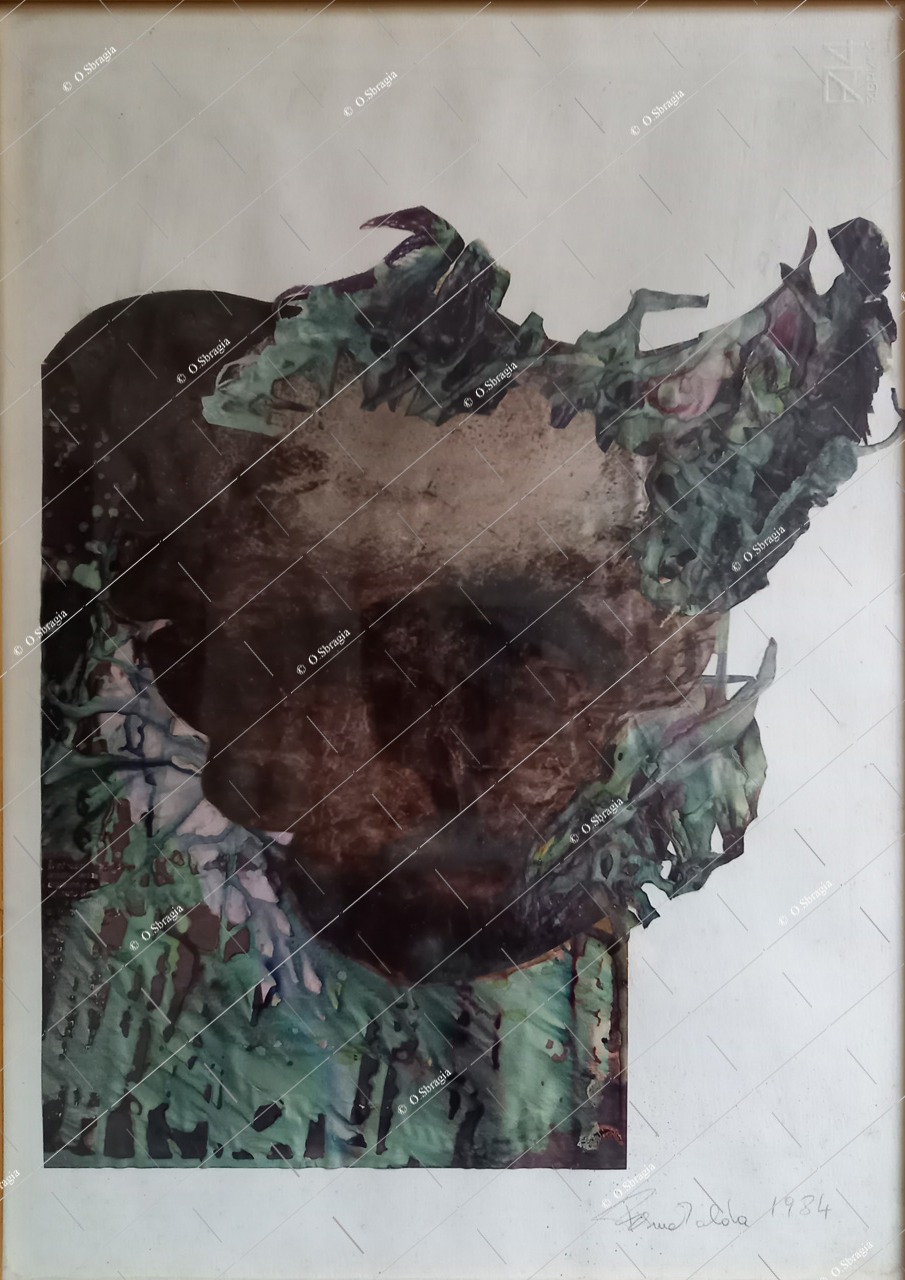

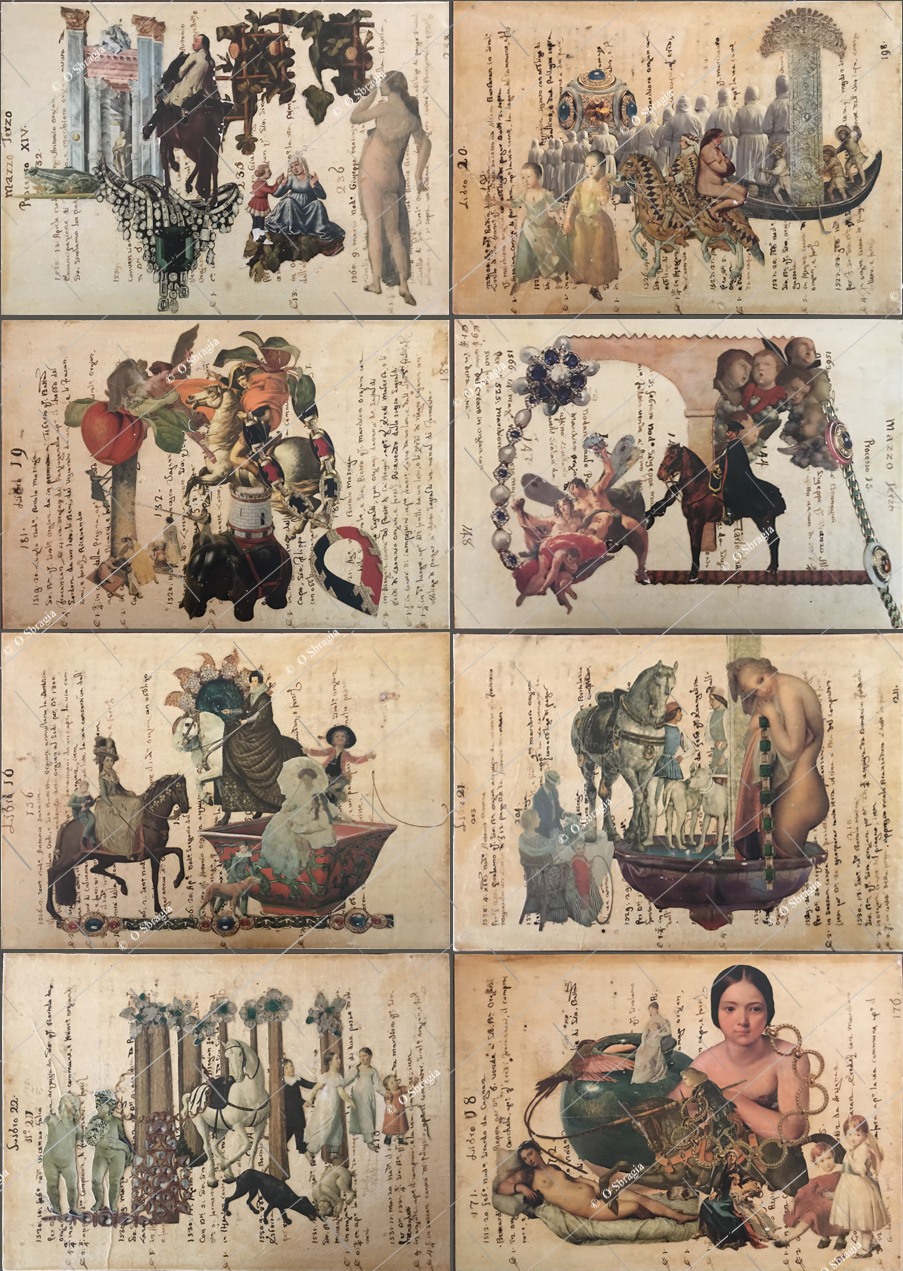

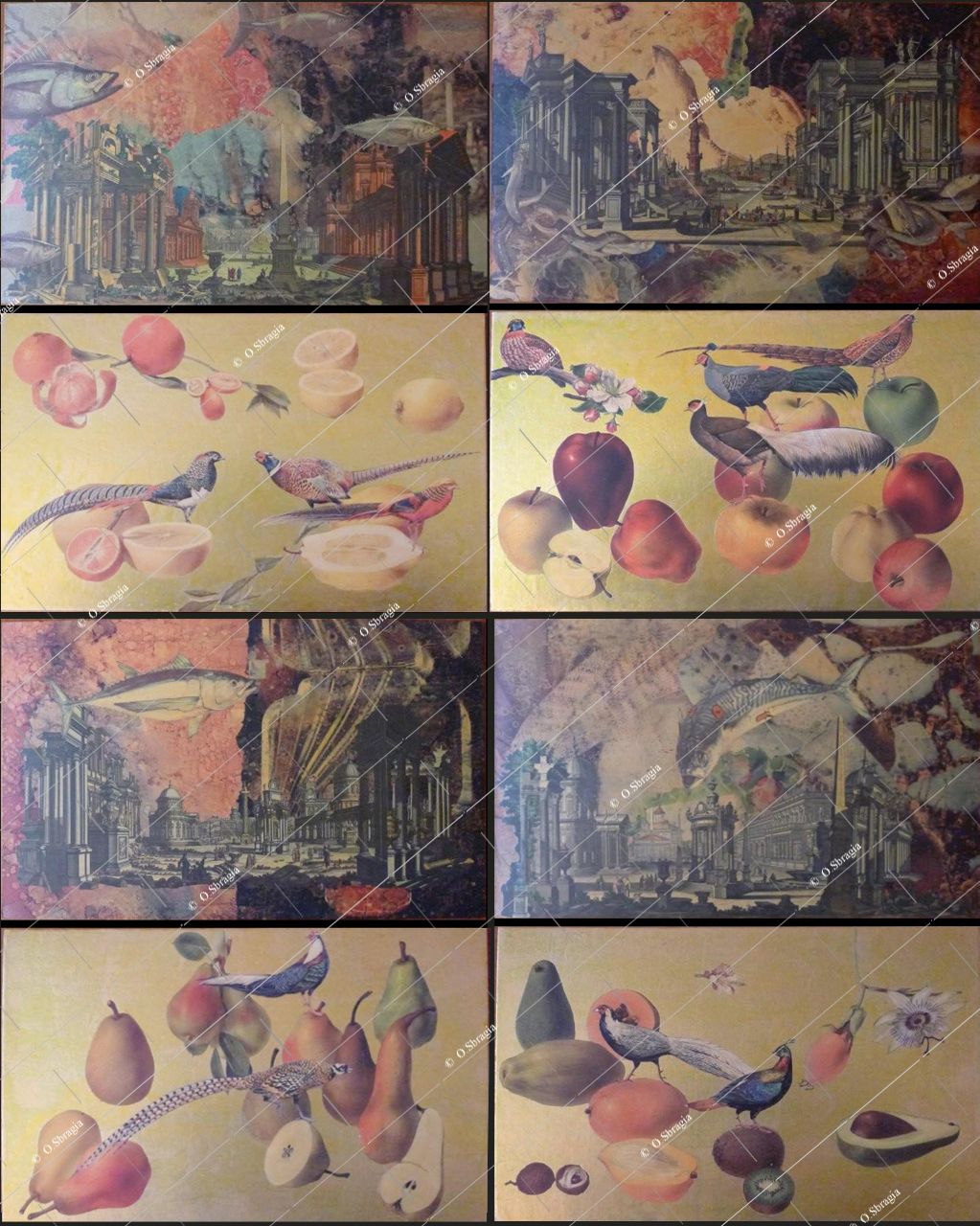

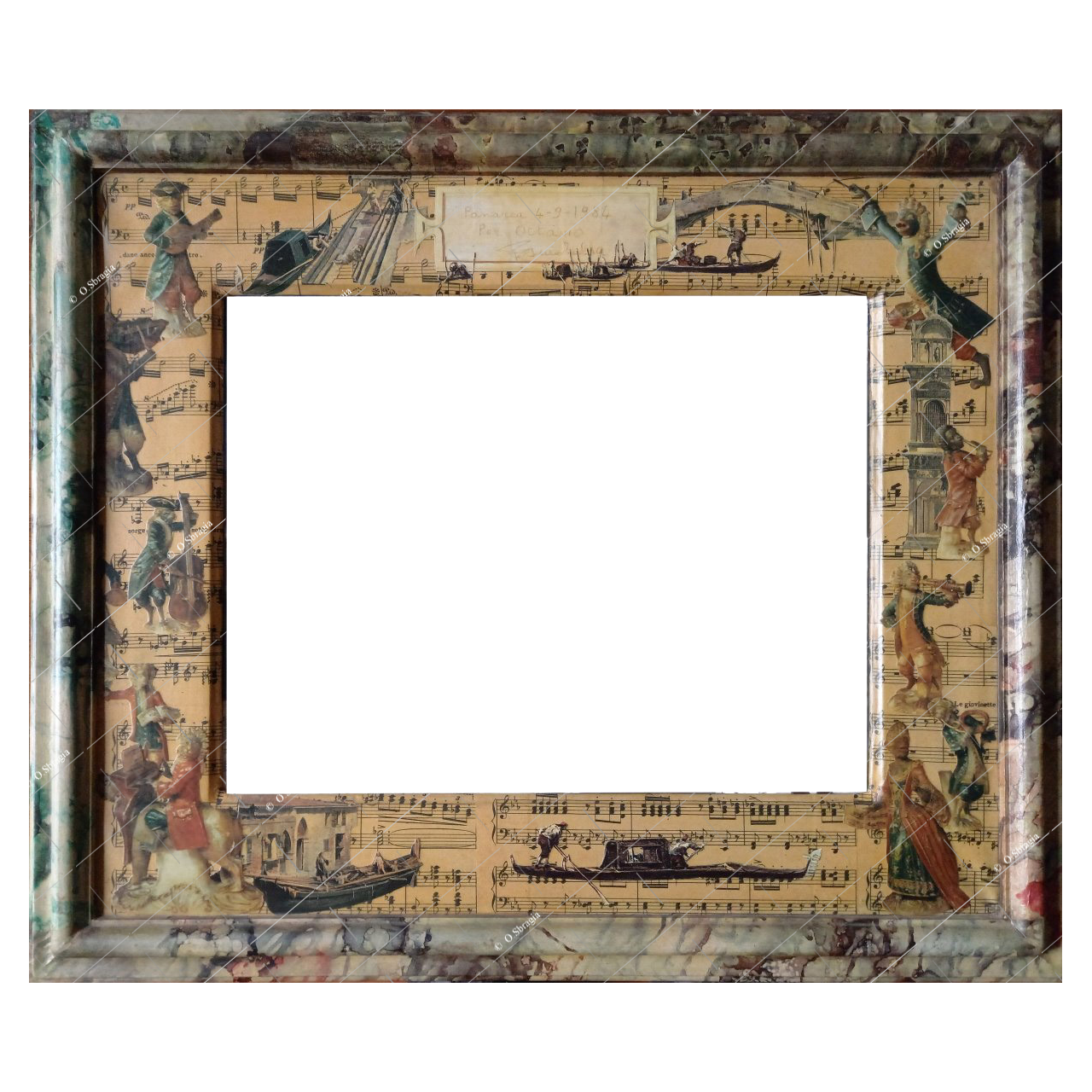

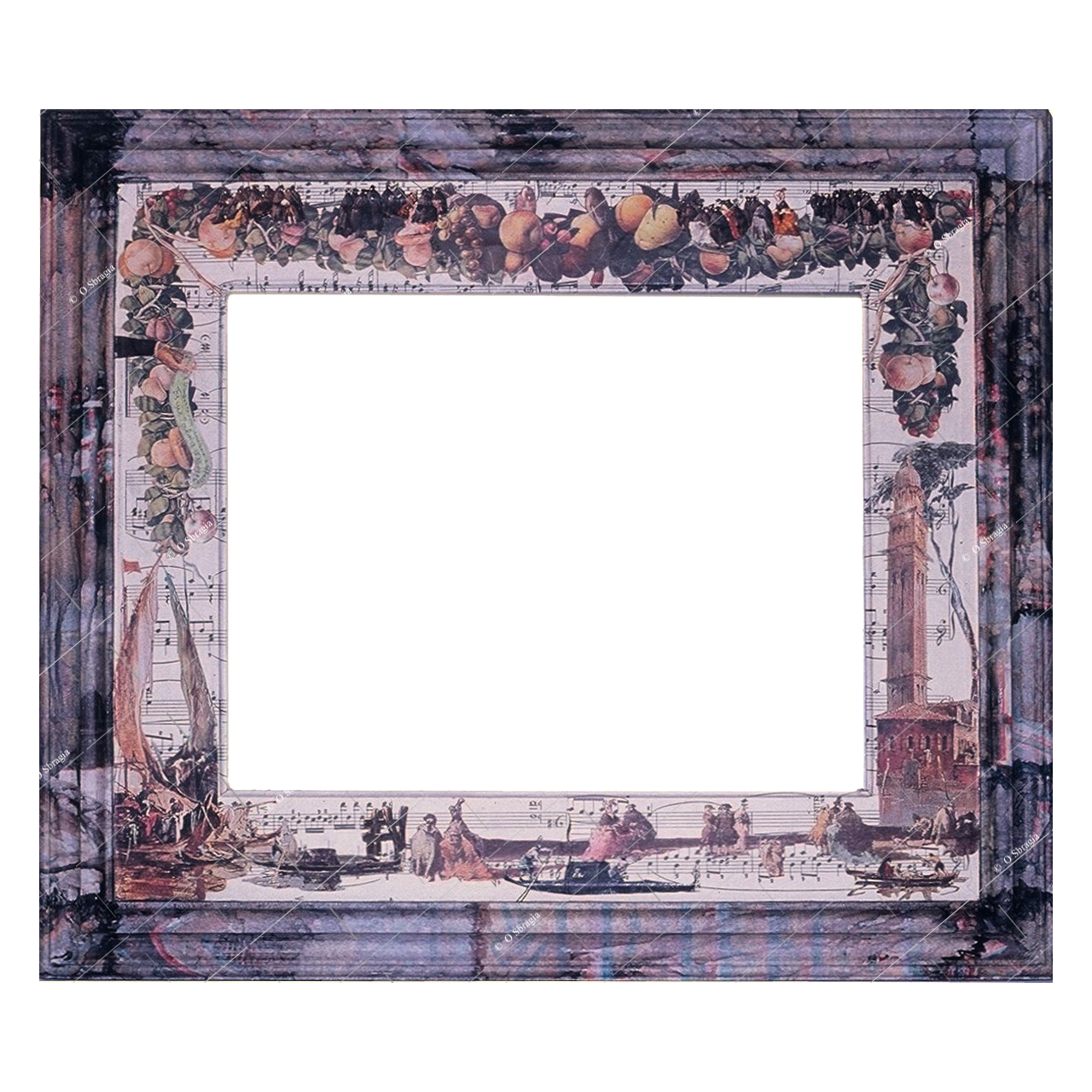

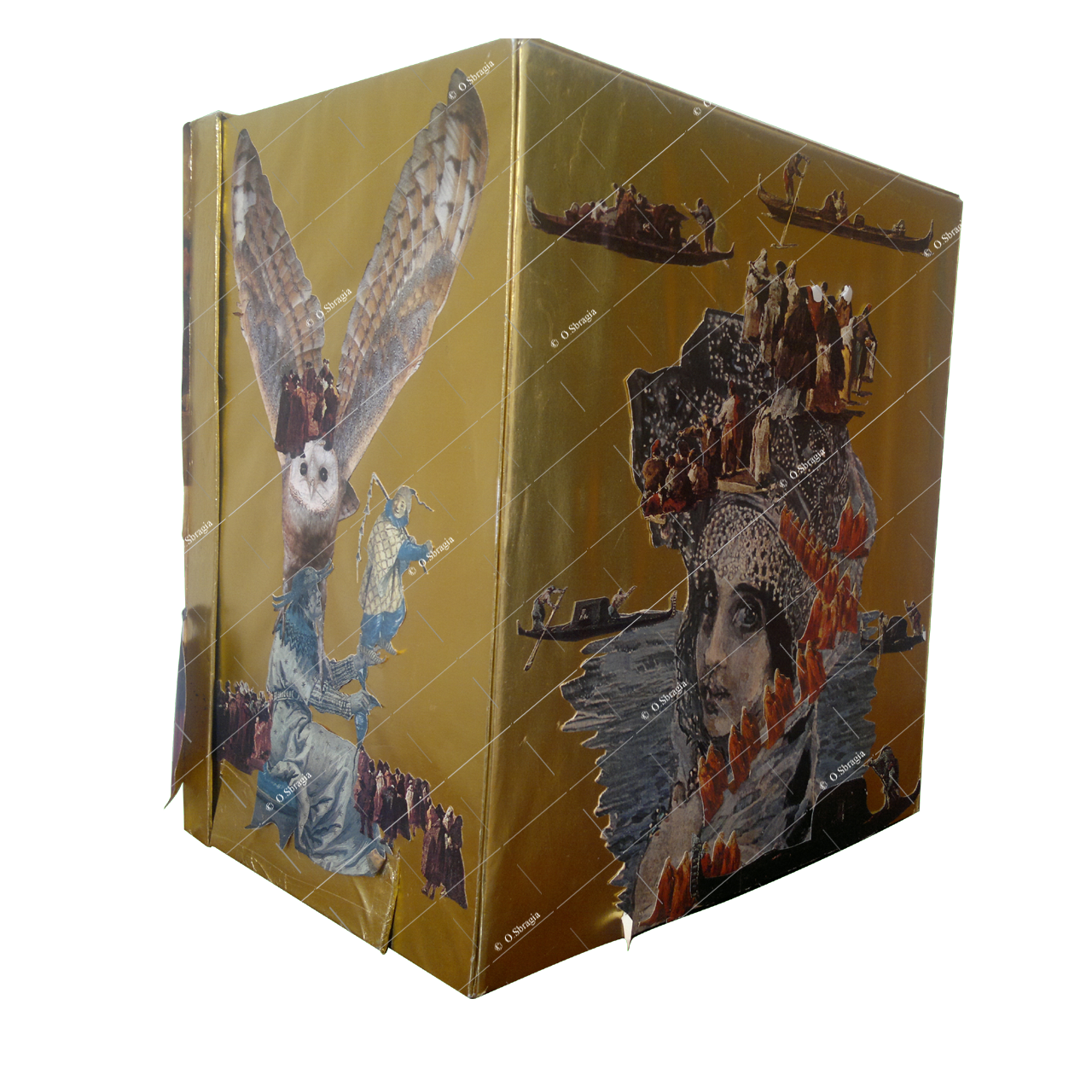

so leaving the page and entering her hands are the gondoliers and chimneys of Carpaccio, the masks of Pietro Longhi, the street markets

of Canaletto, the landscapes of Tiepolo, the greyhounds of Veronese, the forests of Paolo Uccello, together with the faces of people,

marvellous photographs of nature, of birds, of trees, of animals. Some of these cutouts will be saved while others wait to be transfigured

by an acid that decomposes their molecular structure, dissolving the contours and creating an amorphous spray or marbleised effect, a

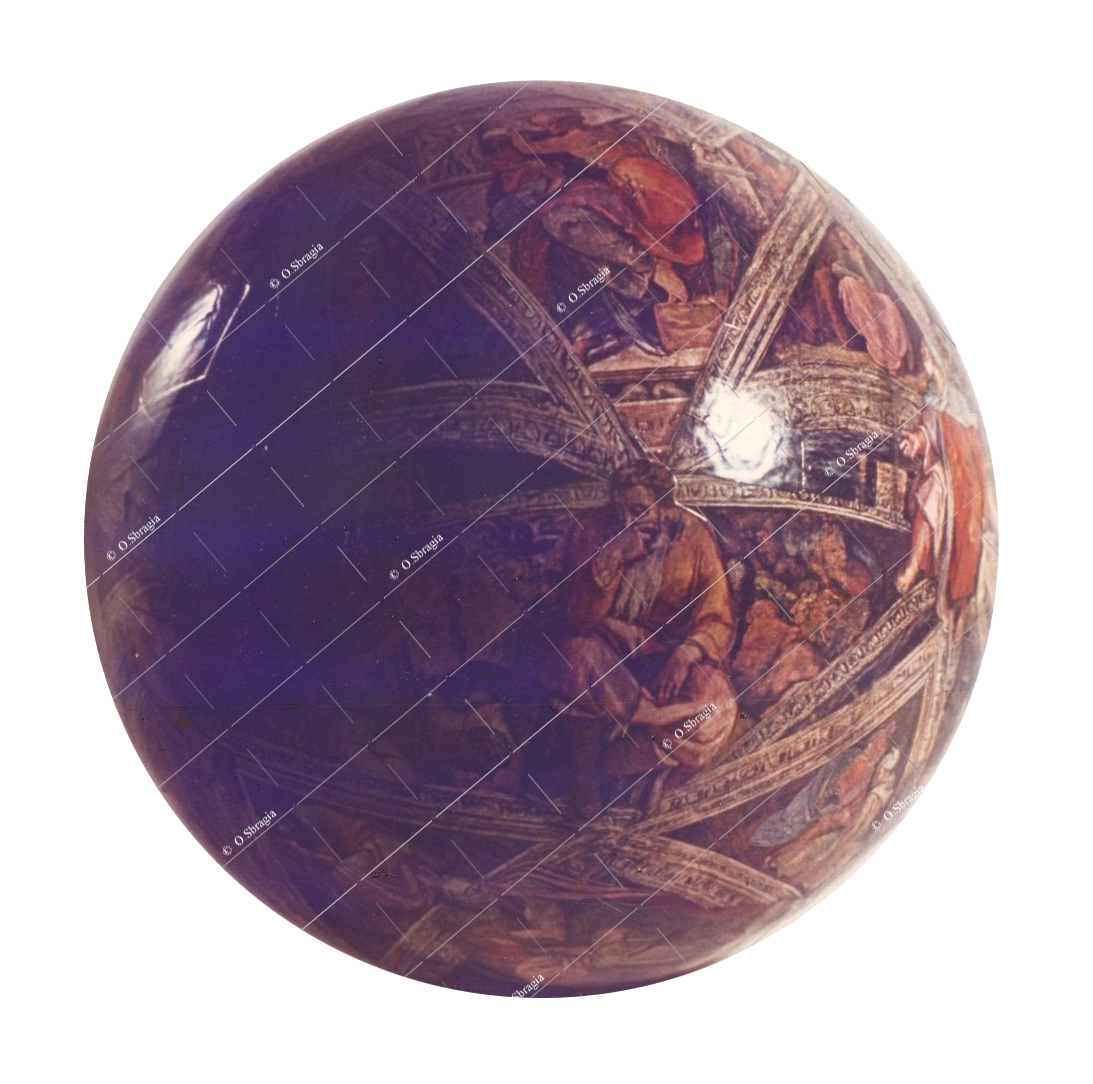

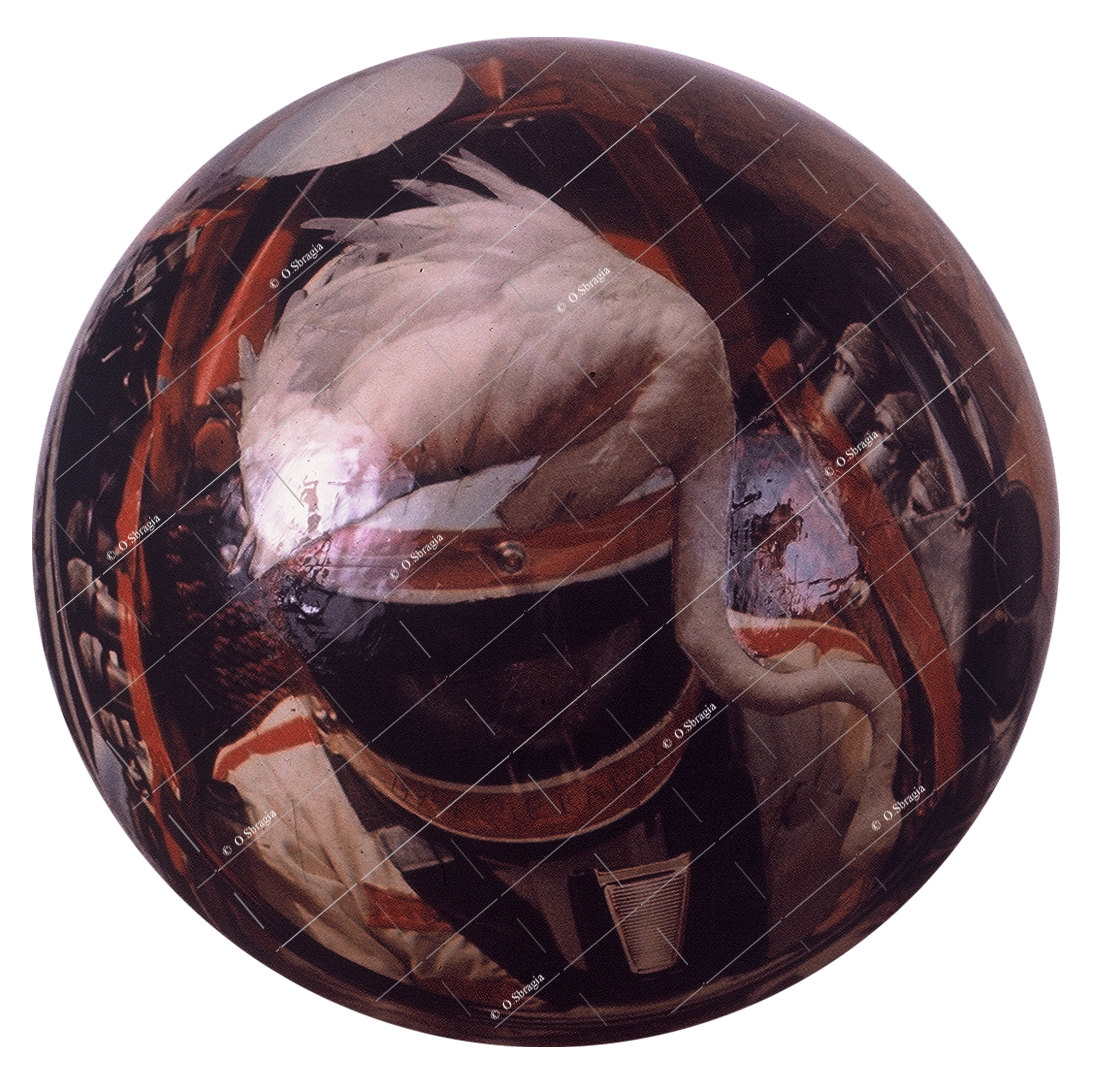

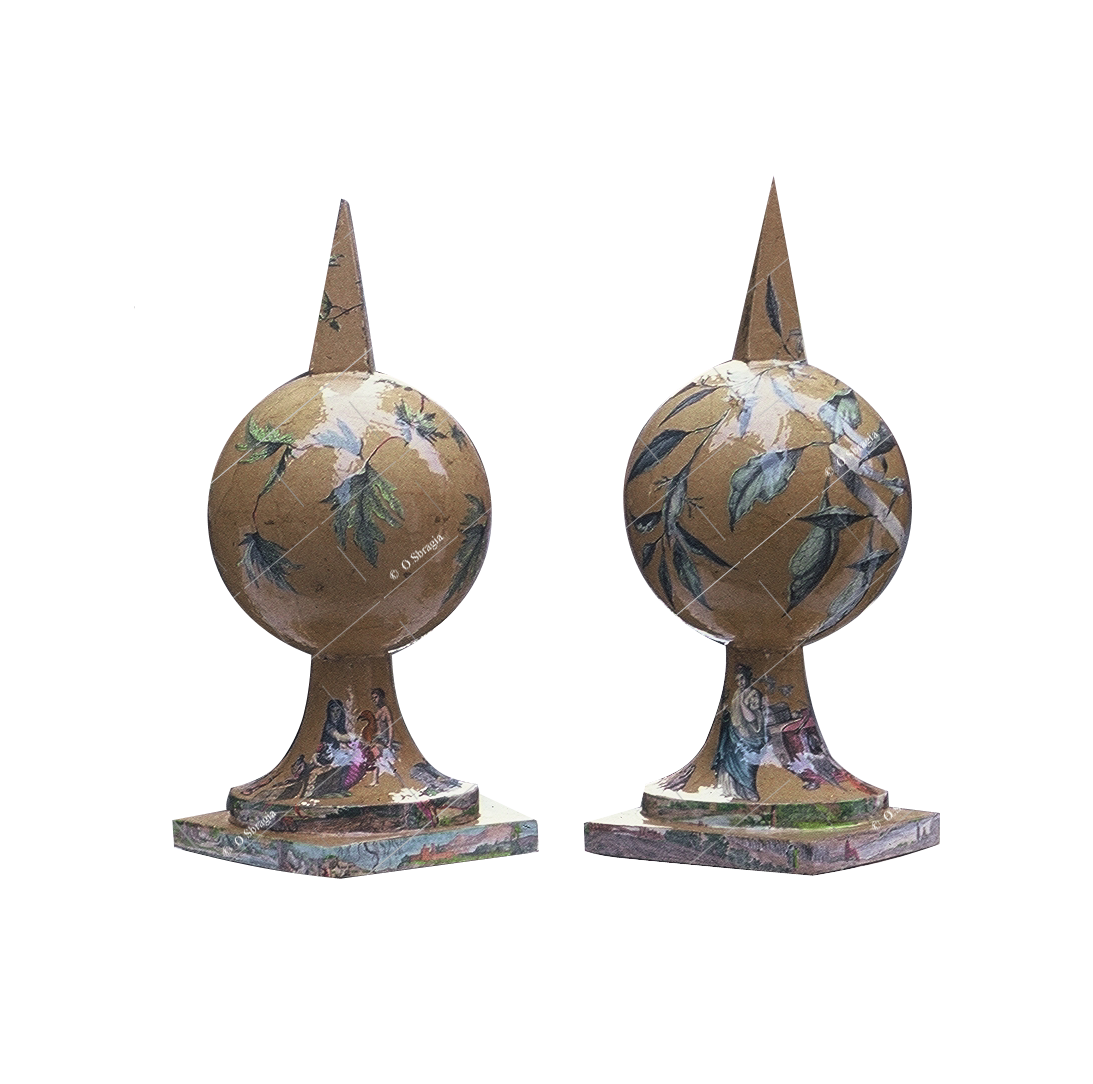

mÚlange of superimposed colours. At this point, the objects enter the scene to become, we might say, 'esmeraldised'. These cut

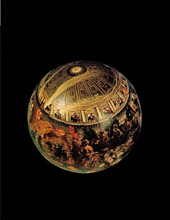

outs and papers treated chemically are then pasted onto the piece of furniture, the table, the sphere, the obelisk, the tray: they become

supports already endowed with a form and function for the compositions of Esmeralda. We could commonly define them as collages; instead

they are instruments of adaptation and re-appropriation of the world. It is too simple to make a picture; above all it's not comprehensive

enough. Esmeralda projects her vision onto all things; she wants to see them as she feels them. She does not accept the material as it is

offered. She wants to correct the creation of the form. It is a matter of a procedure of homologation, indifferent to the variety of things

and totally inclined towards their unity.

And in this parallel world, it does not come from her intervention on things but rather from their original form, so that a plate remains

a plate and a sphere a sphere, in the majority of cases without even departing from their function which is the reason for their diversity.

We might therefore call Esmeralda a decorator, were it not for her vision which touches the limits of obsession and is indifferent to

discernment: I am certain that were she able, she would extend her method and desire appropriating all objects even architecture. She would

'esmeraldize' the Palazzo Chiericati of Palladium or the Church of the Redentore and maybe even the villa of Maser. She would probably

be satisfied with the already capricious and bejewelled Basilica of San Marco, while she would find the fašade of San Petronio in Bologna

culpably unfinished. These interventions of hers have nothing to do with capriciousness; they are quite methodical and rigorous, and I believe

that the intention is to represent the superimposition and summation of images of reality with the historical and personal memories that inevitably

crowd her mind, as they do our own. A sort of filter that makes us associate what we see with a prototype or reminiscence from the past. Esmeralda

registers these apparitions and superimpositions. While she looks at rooftops and the lagoon from her Venetian home, she immediately evokes the

canvases of Carpaccio, this vision blending with the first into an indistinct magma of forms and colours. This then is how the disintegration of

images is created with a coagulating effect, like a paste that holds the form of the object together and binds it to its new composite surface.

This vision is both baroque and decadent, two words once unfavourable and today re-evaluated, but we feel need of them like an avowed instinct,

not a pastime. Perhaps it has to do with an escape or a refuge, an obstinacy in not recognising the purity of the forms. It may be that in her

dream Esmeralda wishes to give substance to appearances.

[hide the article]

Carlo Montanaro

Nuova Venezia, 28 May 1986

Esmeralda Ruspoli shows her 'collages' but the cinema is still her first love

[read the article]

[hide the article]

Friends no longer even notice, but a stranger, on watching her assemble a źcollage╗, is overcome with curiosity,

because in order to see how it will look vertically after she has placed cut-out pieces of paper onto a base lying on top

of a table, and then blocked it with glass, Esmeralda Ruspoli climbs onto a chair to check. And only when it works, does

she block it all with paste and then finishes it off with varnish.

Starting Saturday her creations (she likes to call it 'arte povera') will be on view until June 5th in a newly opened

cultural space in Venice, the bookstore 'La Soglia' at the bridge of Donna Onesta (we hope it also becomes a place where

people just go to sit and talk) near the Frari.

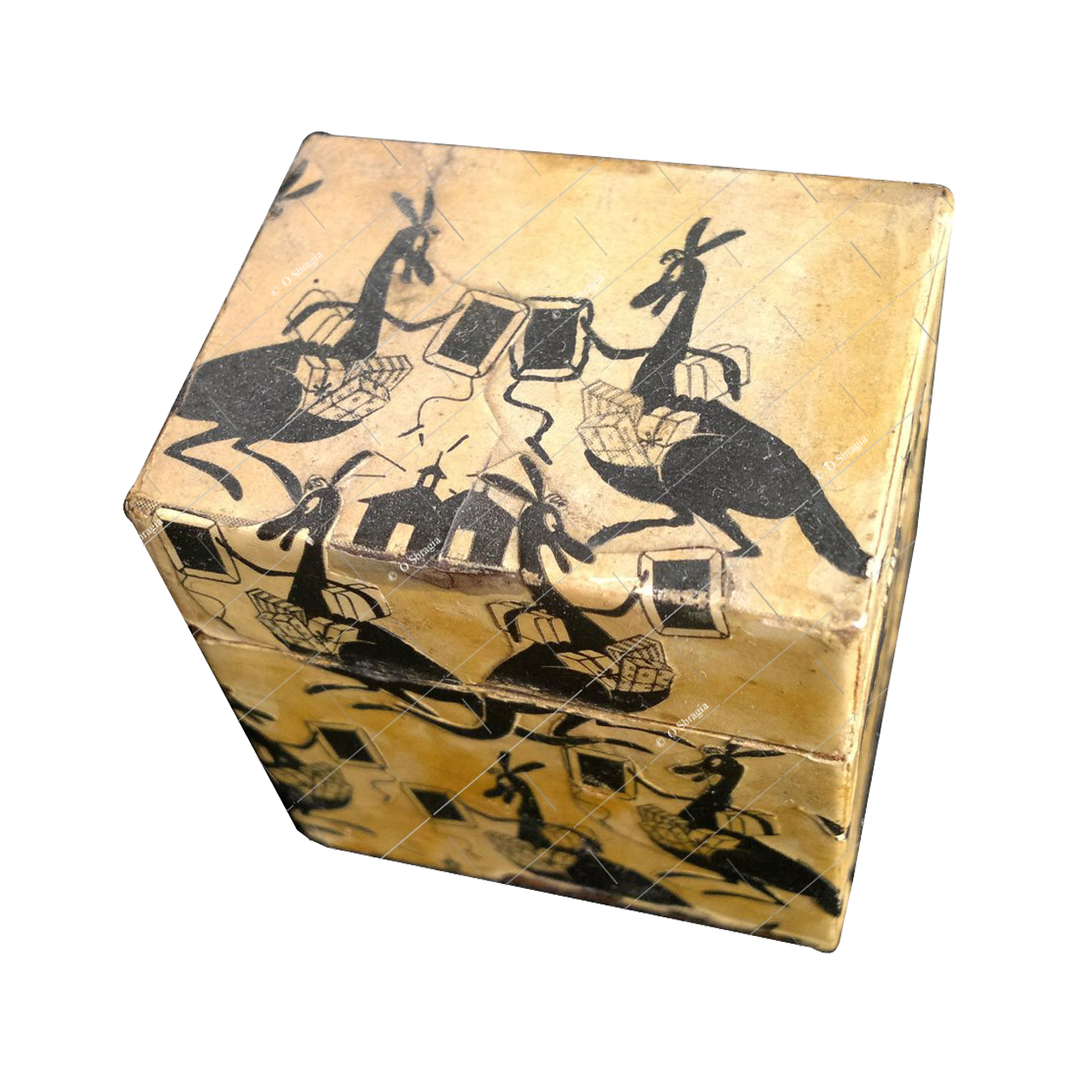

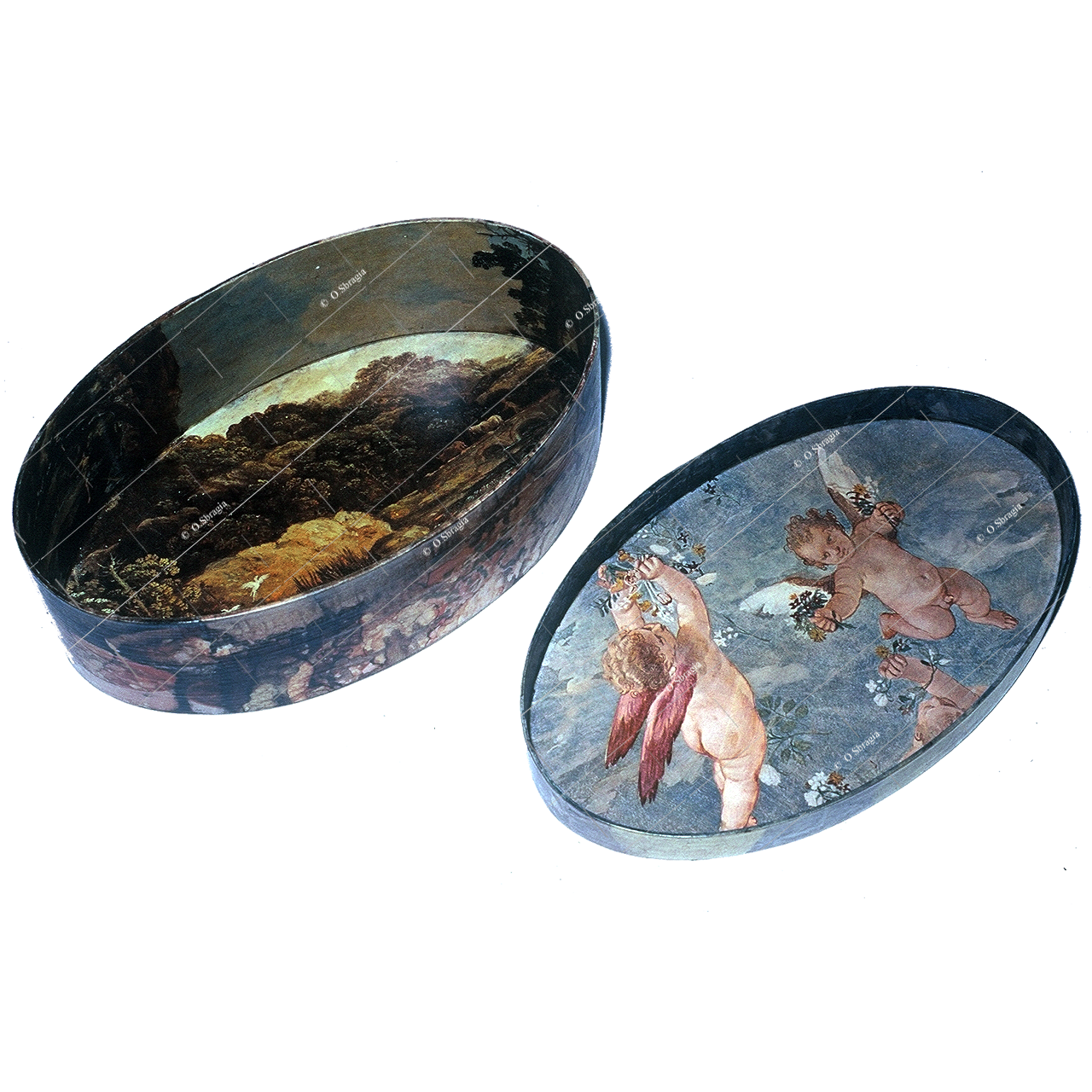

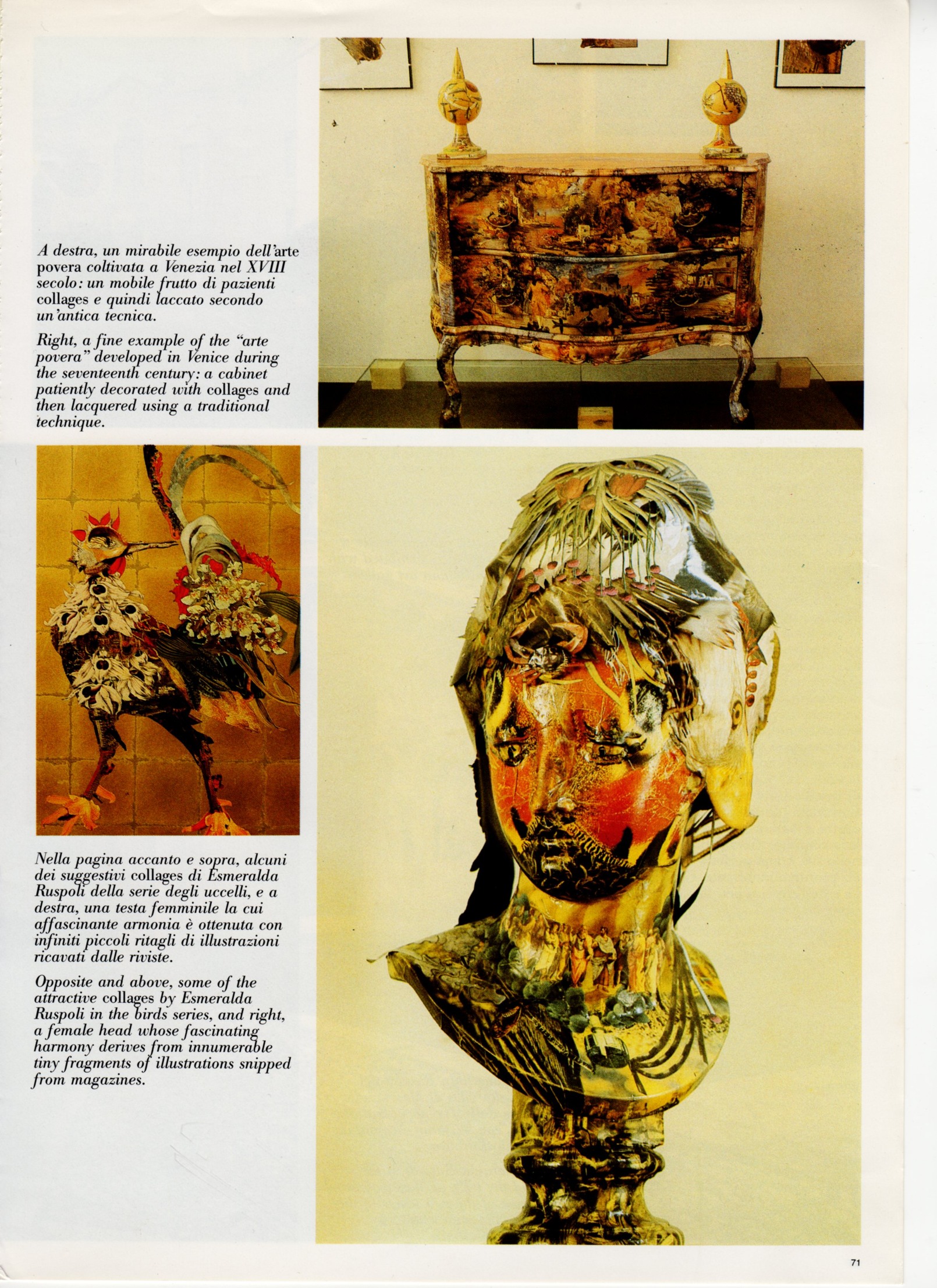

Not only 'paintings' but objects as well: a seventeen-hundreds' style piece of furniture ("an old idea of mine: it's

re-covered not lacquered" confirming the concept of arte povera), spheres, masks, boxes, but also, for the first

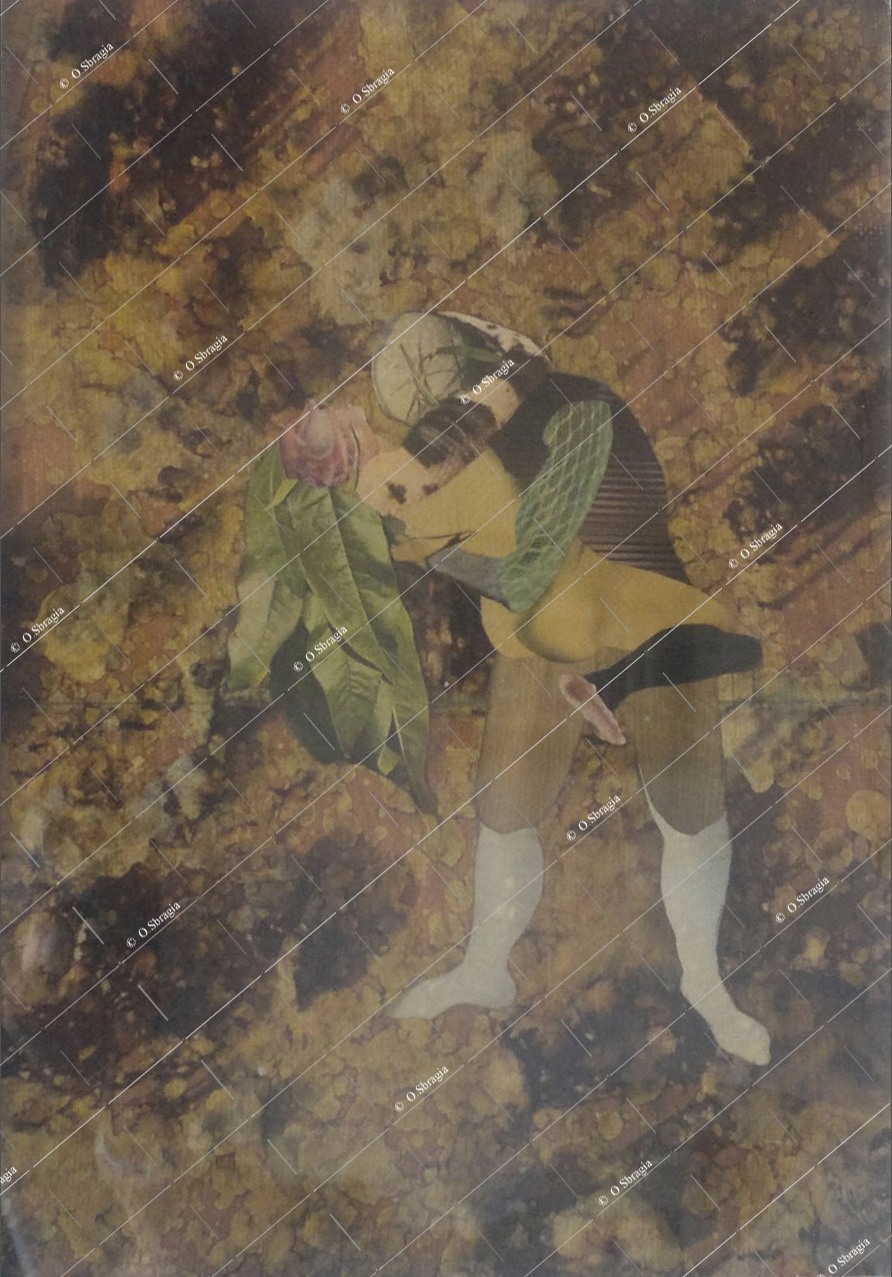

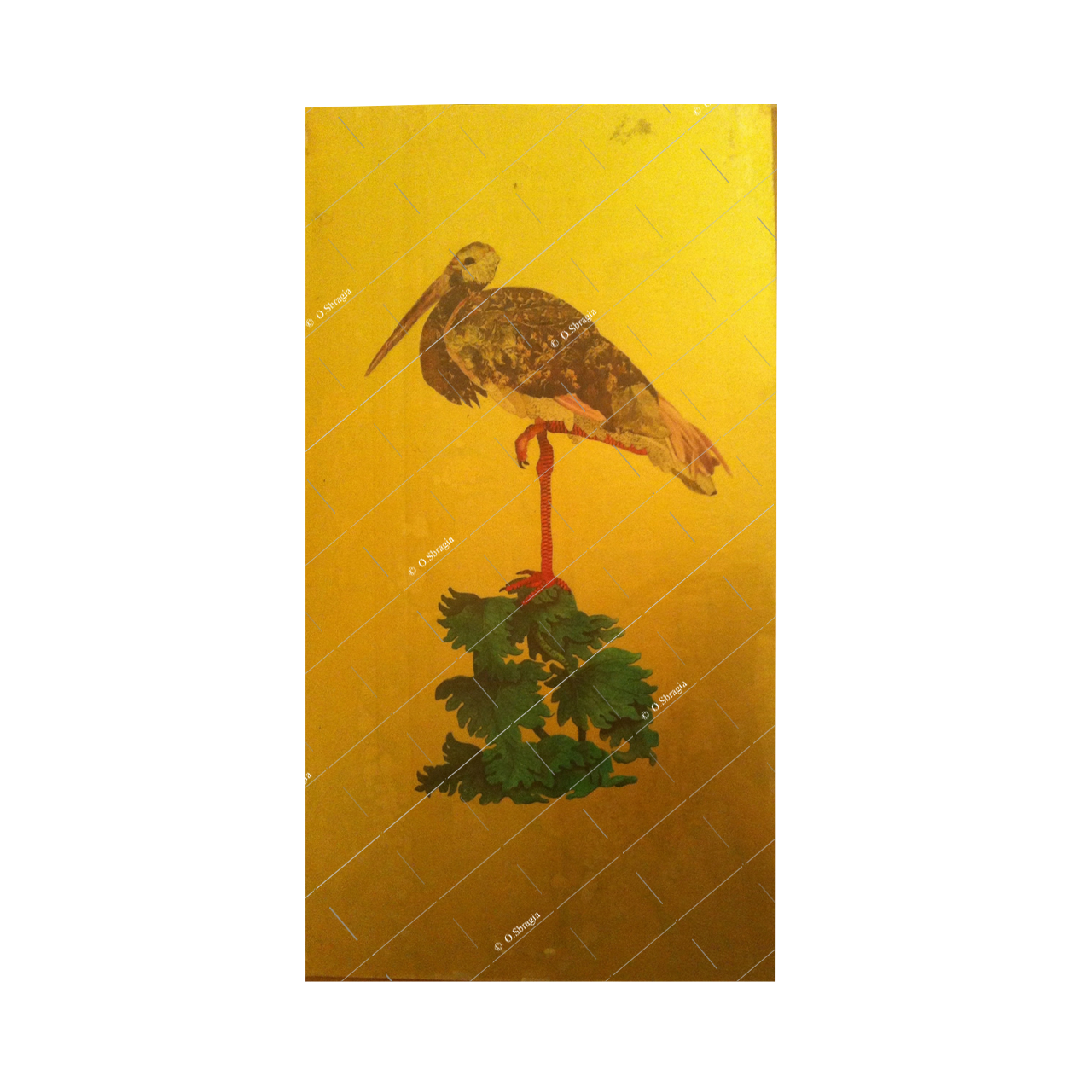

time, re-elaborations on the typical Venetian 'gold background".

Esmeralda Ruspoli, Roman by birth, is also very Venetian. And it was from her grandmother Volpi that she inherited a taste

for painting (but, as was done in those days, she had stopped when she married) and then, it is not known how, she found in

her hand a pair of scissors. When she was seventeen at Maser, her first collage, a door that, albeit not well conserved, still

exists. Then a long pause for the second great love of her life: acting. Which also brought with it a husband (Giancarlo Sbragia,

pride of the Academy of Dramatic Art!), three children (all in the world of spectacle: Mattia actor-author-director, Viola

publicist and Ottavio musician), and at least fifteen years of an honourable career: "They thought I was doing it so as not

to get bored, instead I was a serious professional. In fact, my real career began after my separation from Sbragia. The name

certainly did not help me: while, for my relatives it was unsuitable that a Ruspoli tread the boards of a stage, for others in

that world I was instead stealing bread from others simply for the fun of it. But I loved my work. And seeing myself today in

some films that were made then ("L'Avventura" of Michelangelo Antonioni, the first film in her opinion that took her

completely by surprise; later Zeffirelli's "Romeo e Giulietta", and a few others), I must honestly admit that I could

act in films, I was good. However, that something extra never clicked, I kept on playing small parts, guest appearances: in one

word, hookers!"

Pleasant, open, self-assured though apparently timid, Esmeralda recounts the events of her artistic career simply and the magic

moment that everyone should have which is yet to arrive for her: "It may well be written that I shall become important playing

the parts of elderly people, old ladies".

Bu she confesses that she'll return to the stage only if her son Mattia asks her to, because such a long time has passed, and because

acting technique.because.because today she much more prefers to do collage. In life, one knows, there do exist courses and recourses.

Esmeralda (the pseudonym appears only with a meticulous construction of her artistic career), for some time now prefers to agree to

the verification at home in Venice. And everything works, honestly: to see is to believe.

[hide the article]

Giuseppina Rocca

Messaggero, 22 giugno 1984

The Importance of Being Esmeralda. When art is identified with a name

[read the article]

[hide the article]

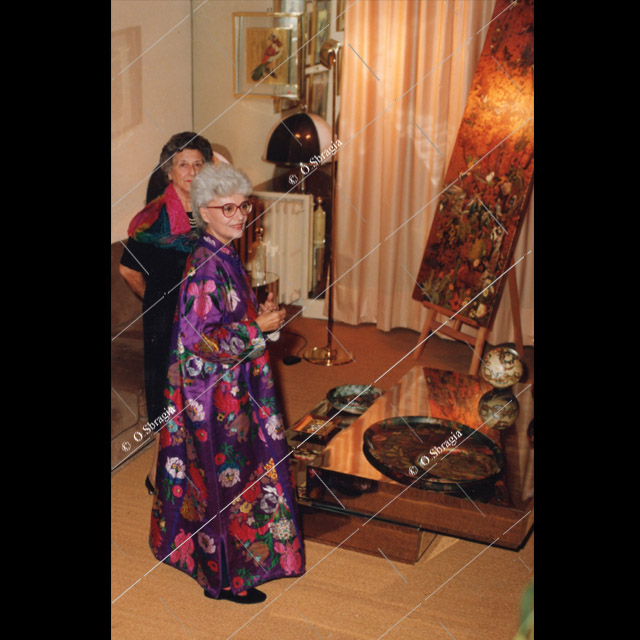

Open-armed as for the prodigal son. So on Wednesday afternoon, Esmeralda Ruspoli reappeared after many years to

present her one-man show of collages and painted objects at the Oro del Tempo Gallery in Via della Gatta. This

Roman for generations - surrounded by friends from the world of show business and culture along with the usual

crowd of society hangers-on - first began this art when she was very young at her mother's villa of Maser.

"It's strange to see so many friends again all together. I haven't seen many for at least thirty years",

said the princess, the separated wife of Giancarlo Sbragia, who is present with their children at the vernissage,

and who, born in Via del Quirinale, now lives between Venice and Panarea. "I abandoned Rome because something happened

inside me. I have no regrets, I am happy to have done it, I wouldn't go back. "

Gentle and smiling, Esmeralda Ruspoli, plunges for a moment into a vortex of memories.

But it is not a day for nostalgia, it is simply a lovely party and she goes on. Fluttering in her long pale caftan and

wearing an ancient Arab necklace of the family, she greets everyone, shaking hands. Present are Dante Troisi, finalist

for the Viareggio Prize, Giuliano Montaldo, Alice di Robilant, Lorella De Luca and Duccio Tessari, Paolo and Beatrice

Marconi, the Sursocks, Guidarino Guidi, Milena Milani who remembers very well the beautiful eighteen-year-old at Venice

'with a head of fluffy precociously white hair'. Esmeralda, a beautiful name, how much has it influenced your life? "

It is everything. With another name I would have become another person". She answers unhesitatingly, instinctively.

Her gaze fixes on her creations, naturally 'esmeraldized'.

[hide the article]

Arianna

CIGA Magazine, May 1984

The Collages of Esmeralda

[read the article]

[hide the article]

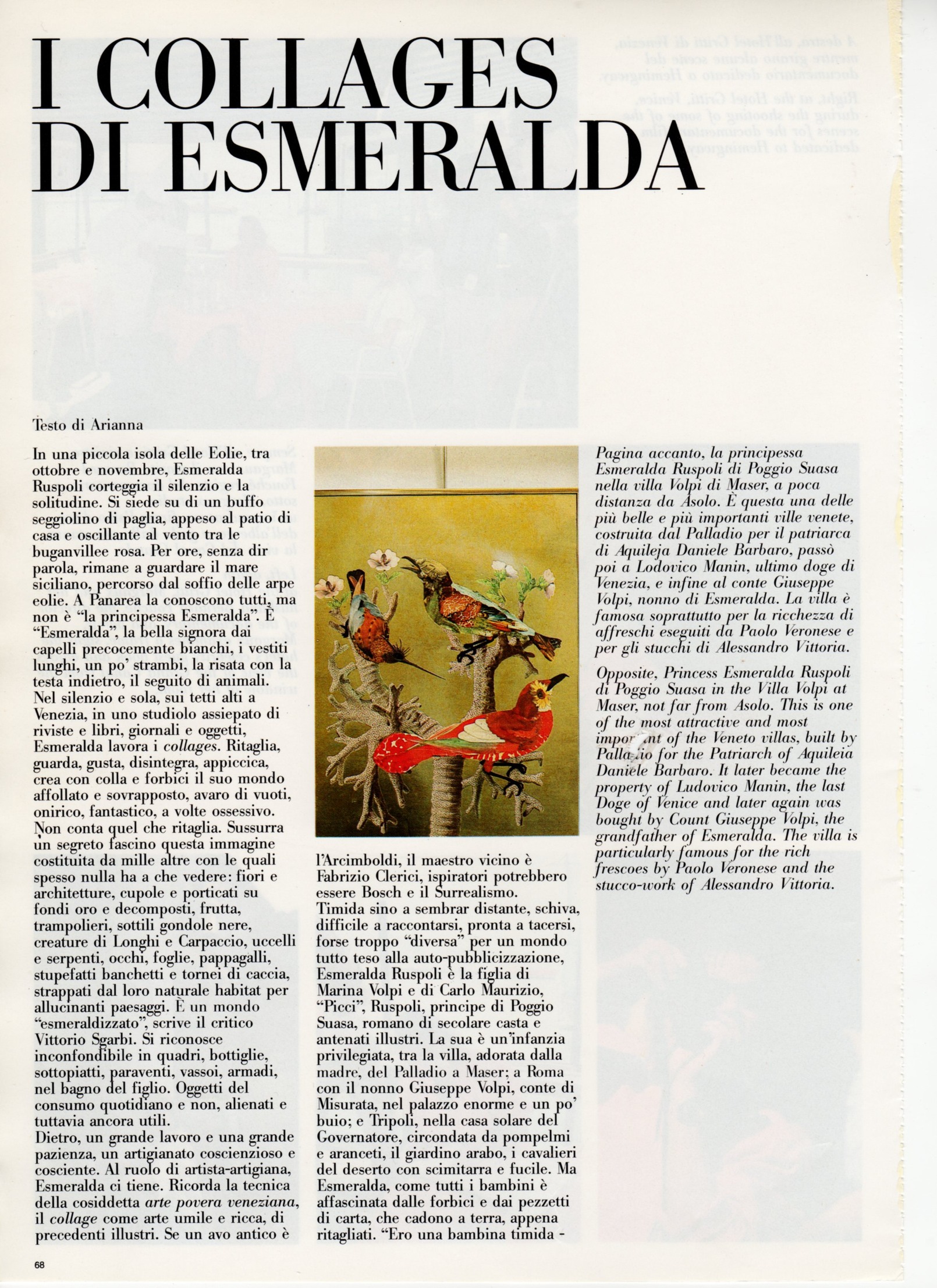

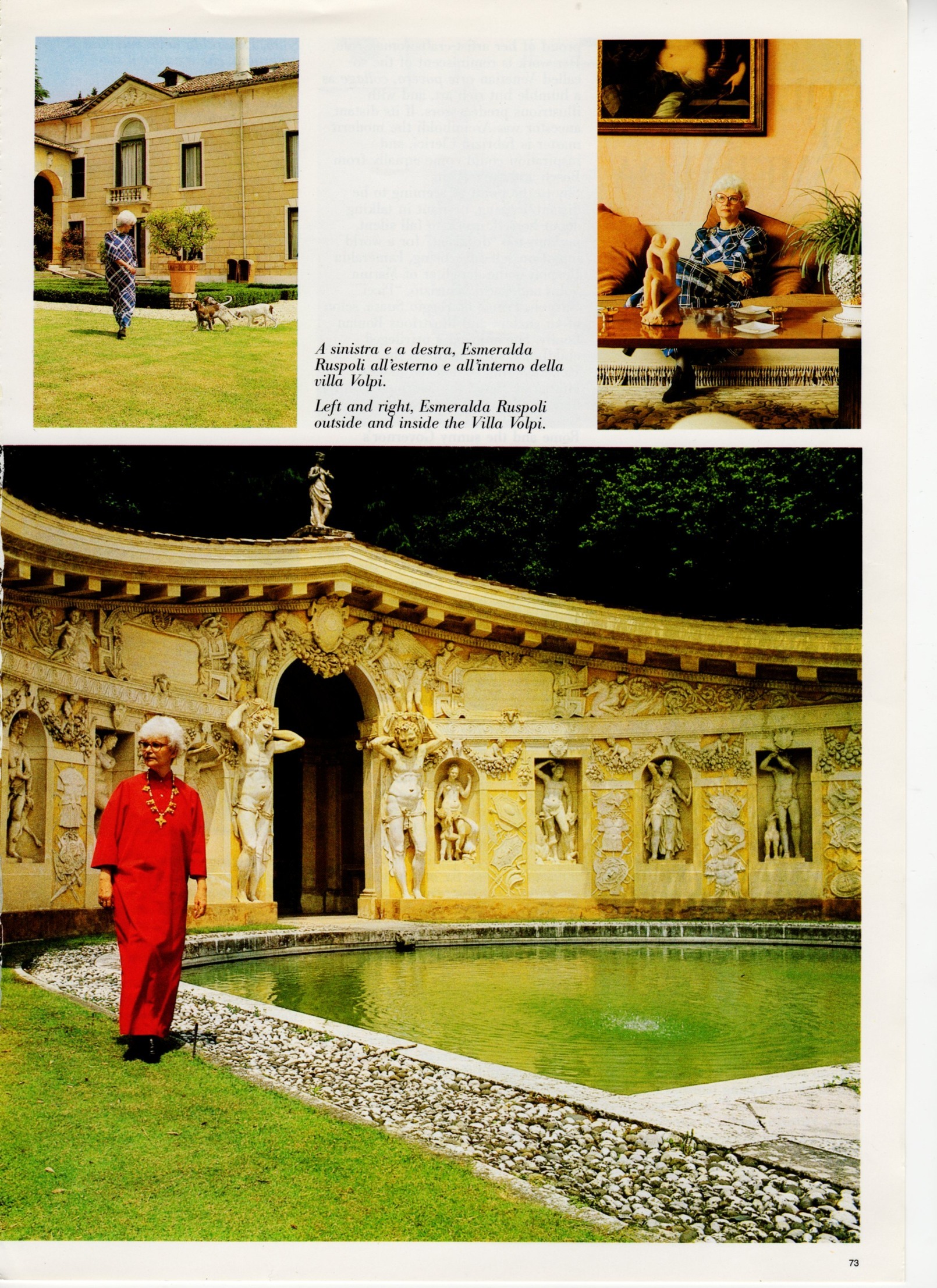

On one of the tiny Aeolian Islands, in October and November, Esmeralda courts silence and solitude. She sits on an odd

little cane seat which hangs on the patio of the house, swinging gently in the breeze amongst the bouganvilleas and roses.

For hours she sits gazing silently at the Sicilian sea. At Panarea they all know her, but not as "Princess Esmeralda".

Here she is "Esmeralda", the beautiful woman with the prematurely white hair, the one who wears long, rather strange

dresses, whose head flings back when she laughs, who is always trailing animals behind her.

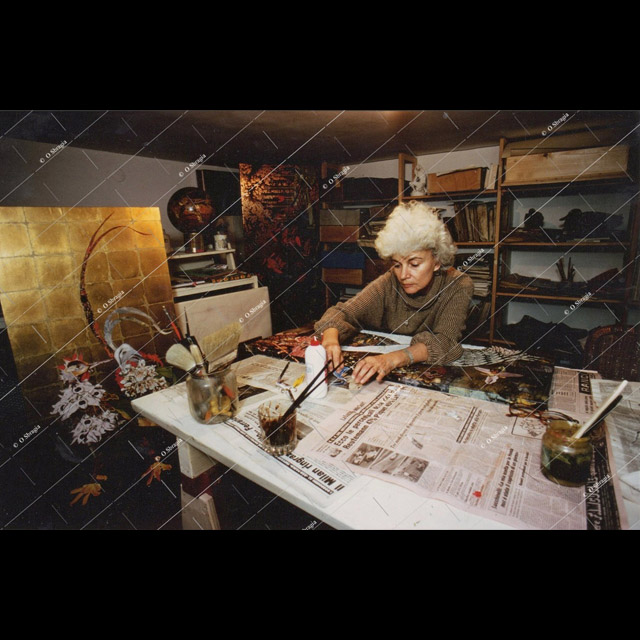

In silence and alone, high

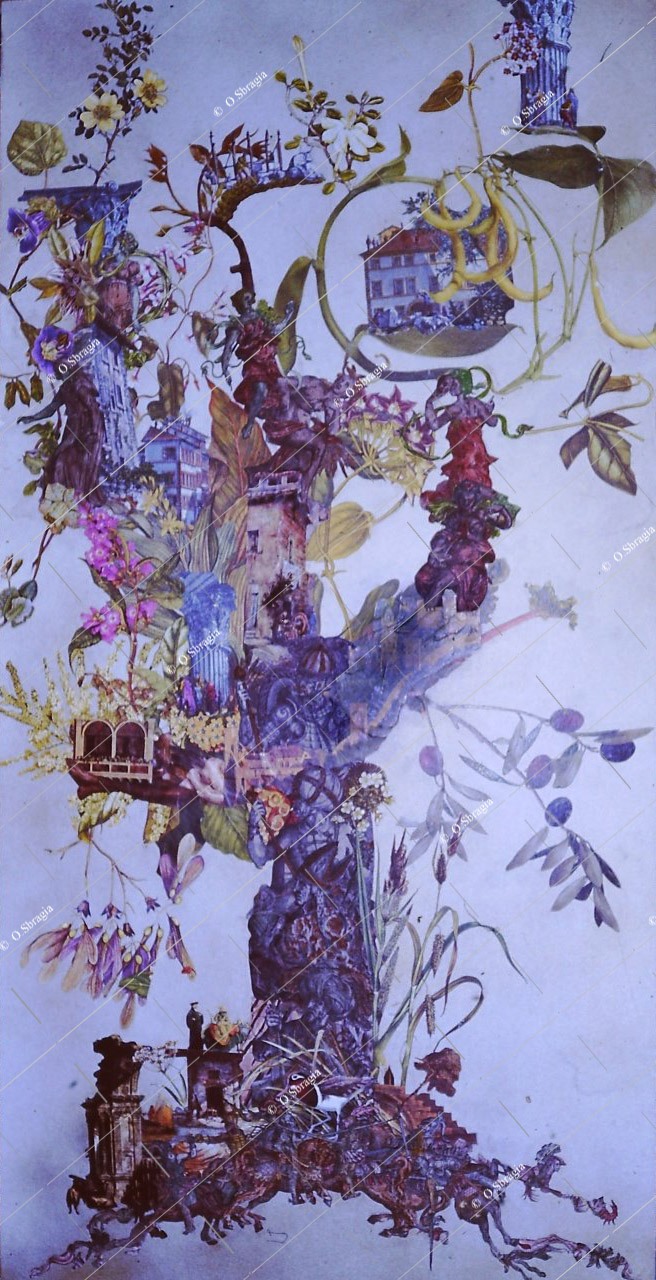

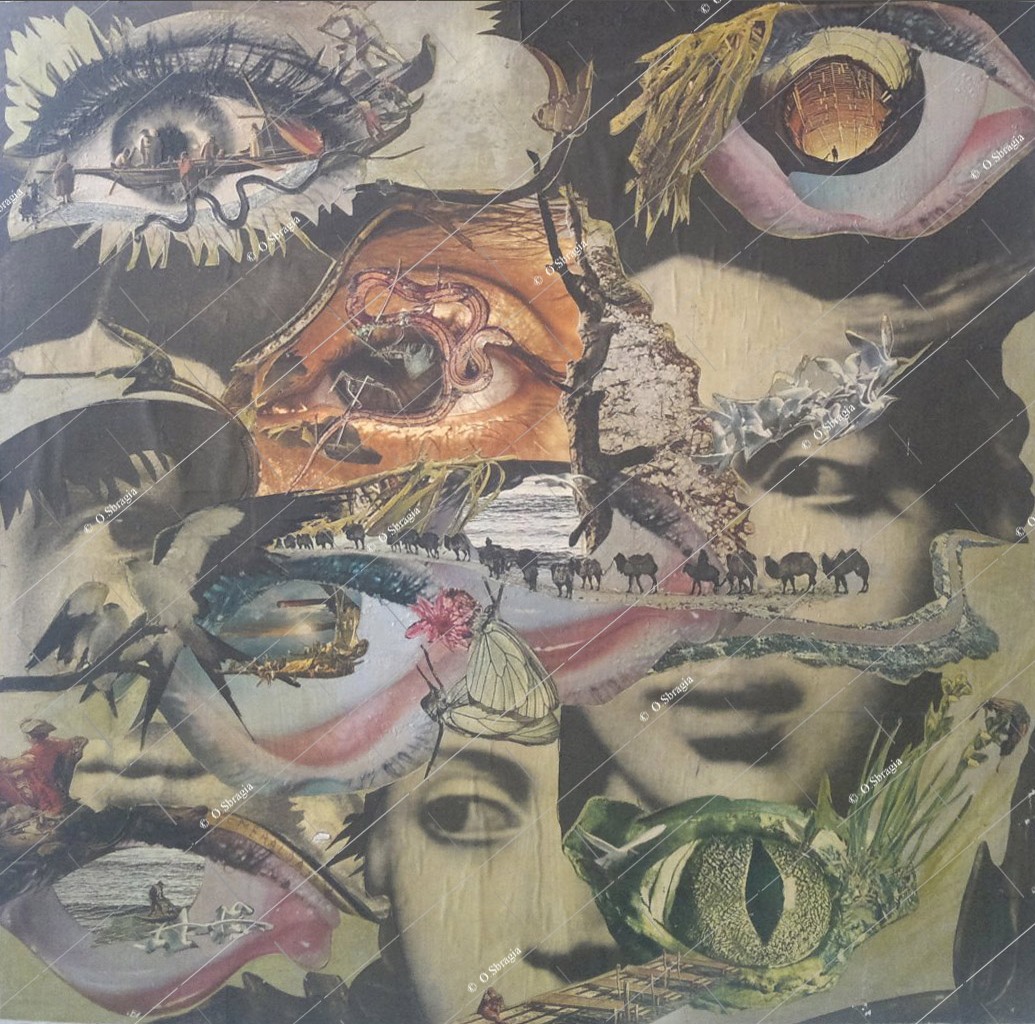

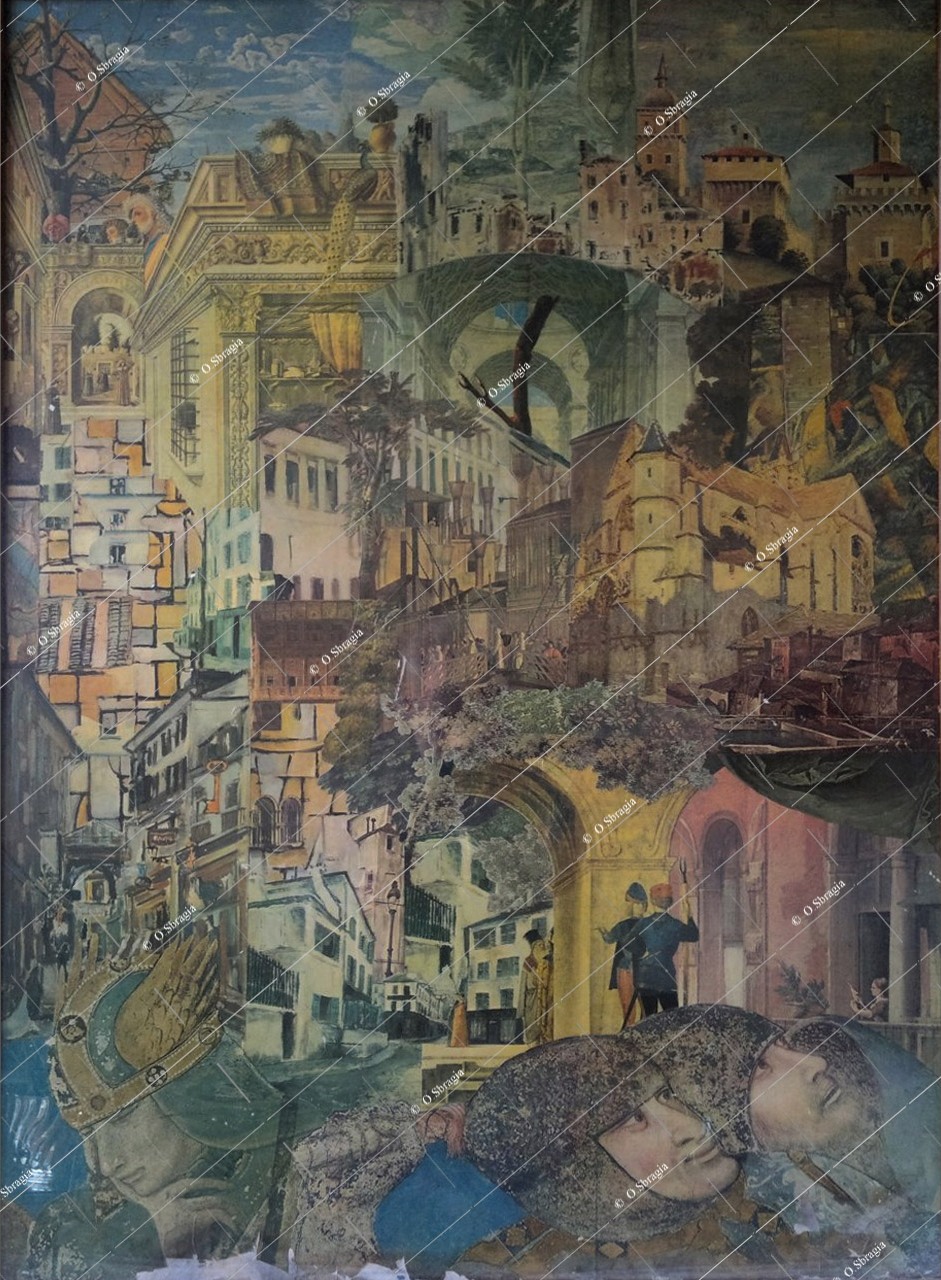

up among the roofs of Venice, Esmeralda works at her collages in a little studio banked high with magazines and books,

newspapers and bits and pieces. She snips, examines, judges, tears, sticks, using glue and scissors to create her crowded,

overlapping world, sparing of empty space, dreamlike, fanciful and at times obsessive.

What she cuts up does not matter.

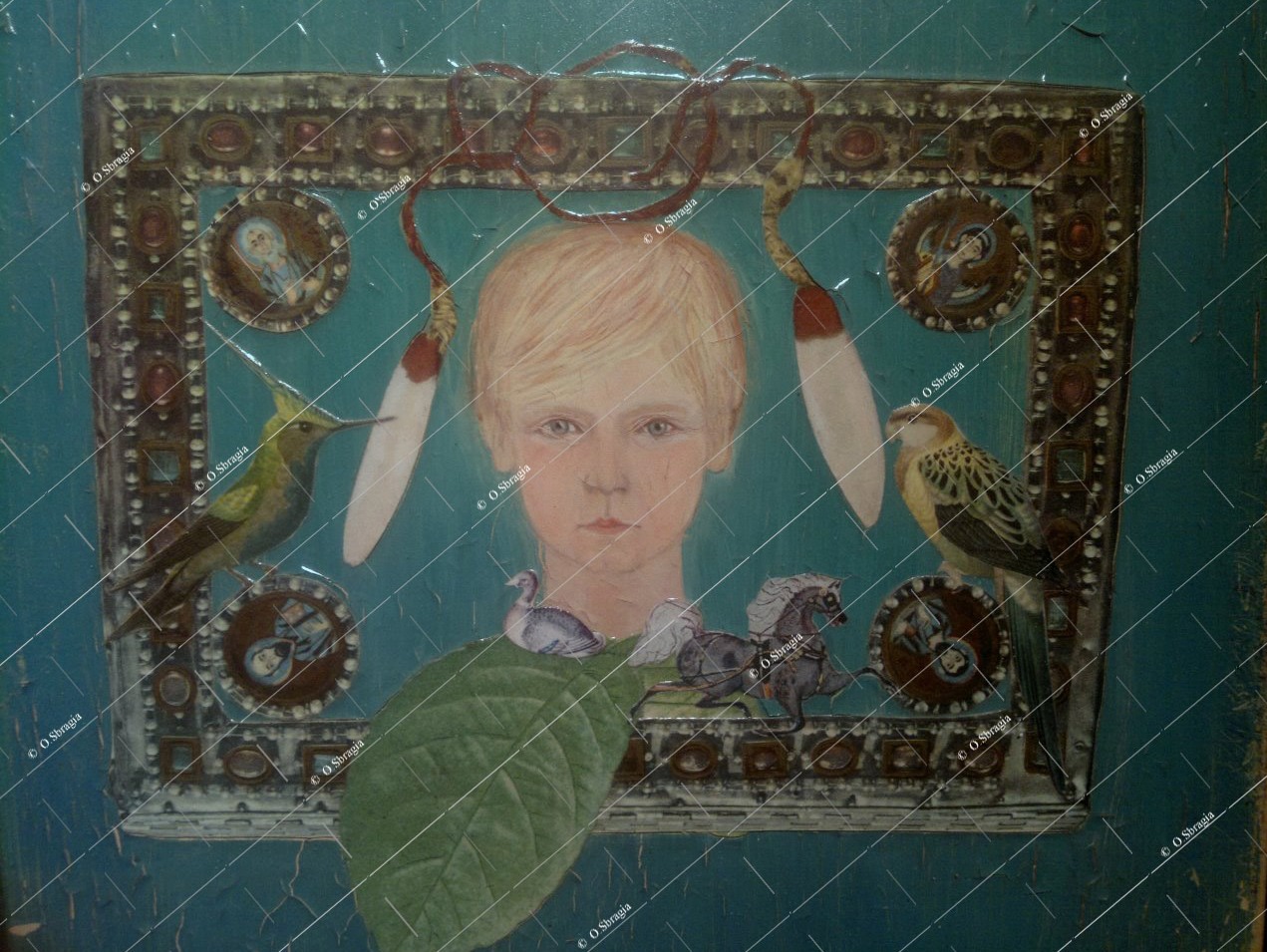

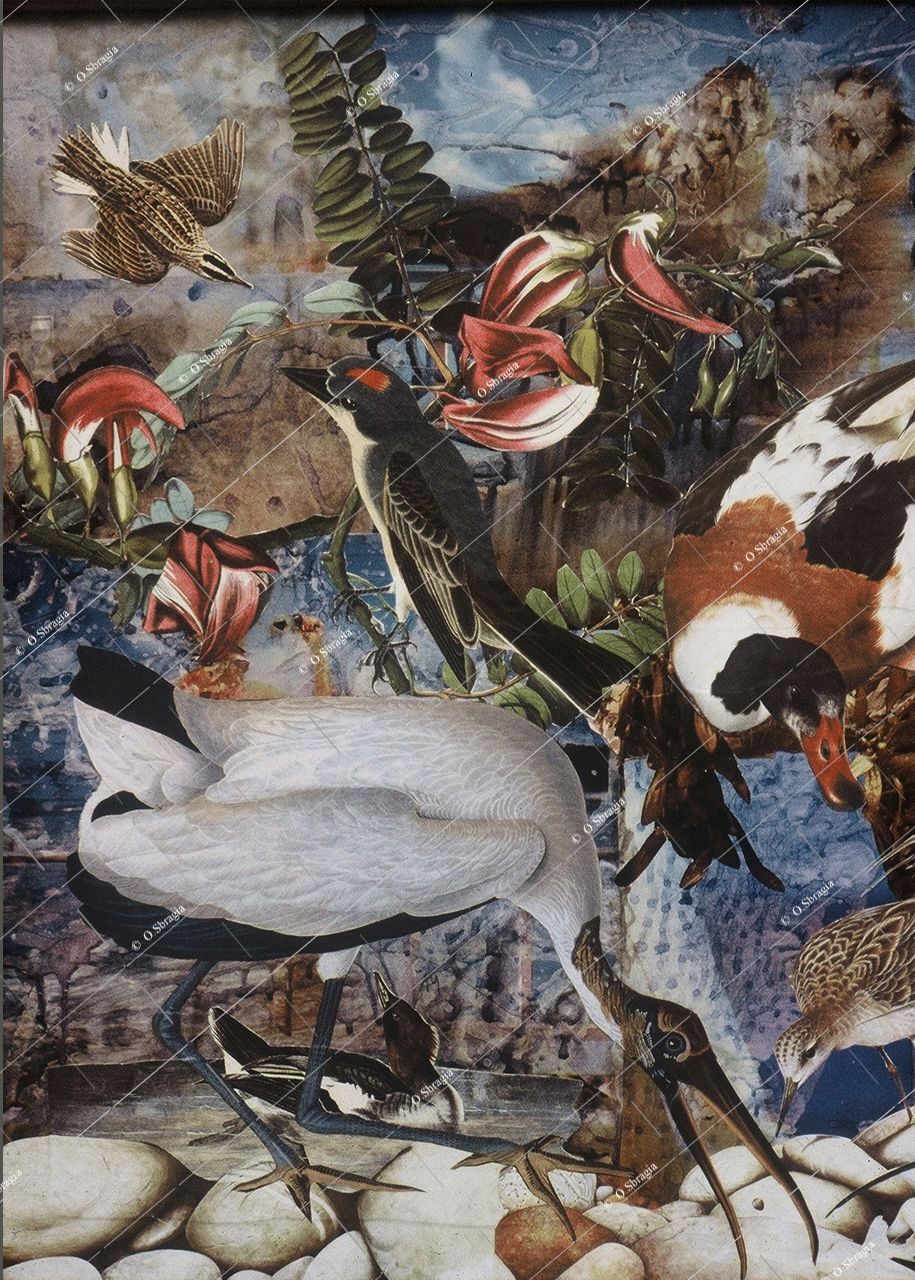

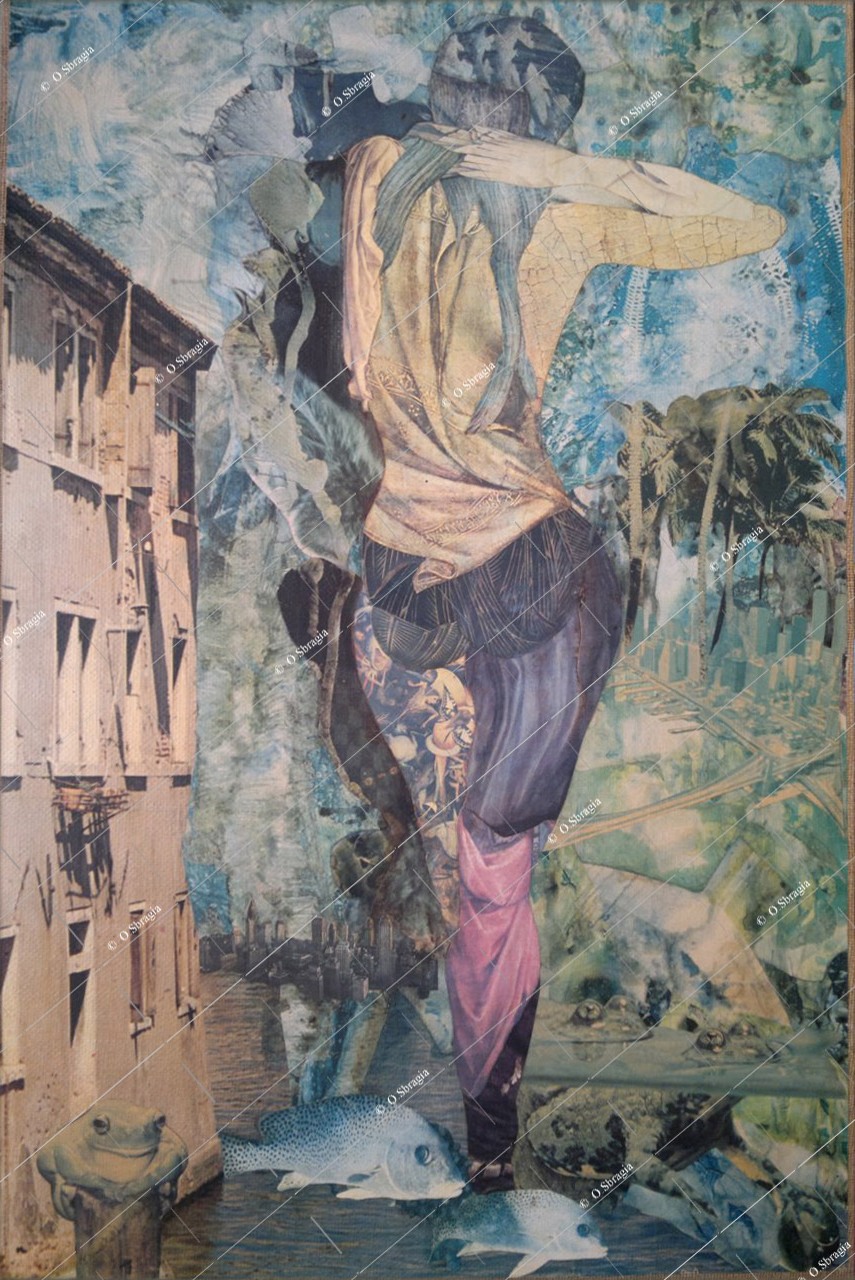

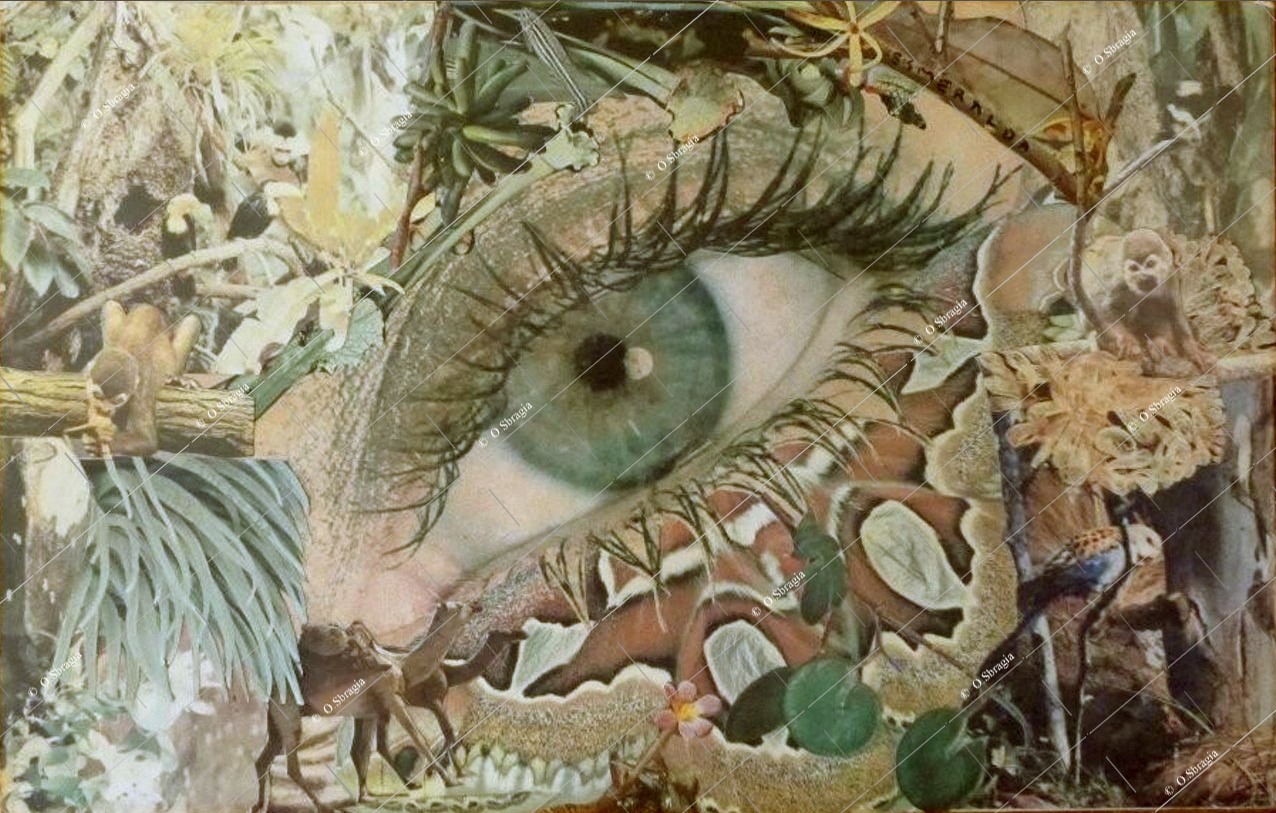

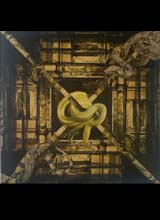

There is a secret charm about the image she creates from thousands of others which often have nothing whatsoever to do with

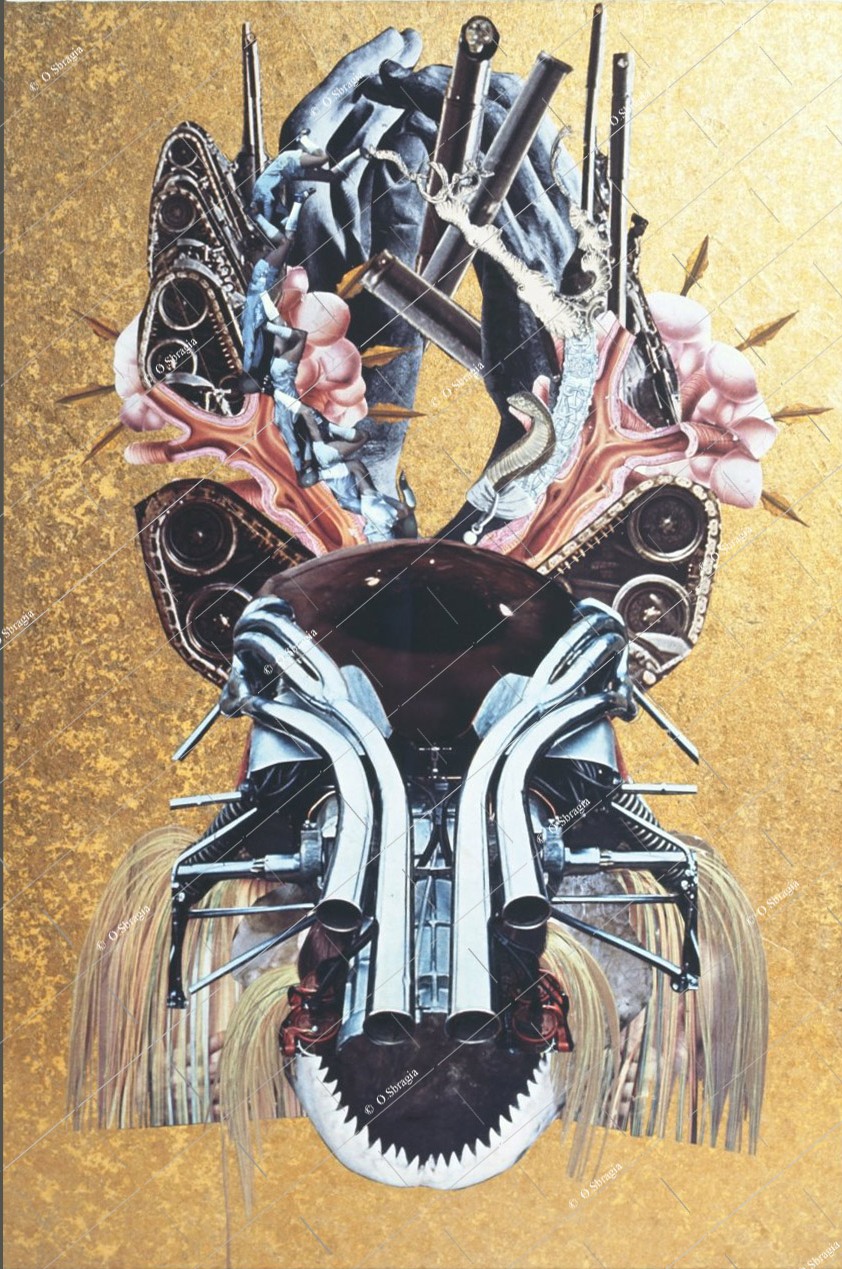

the finished work: flowers and buildings, domes and arcades against uniform gold or fragmented backgrounds, fruit, spindly-legged

water birds, slim, black gondolas, a creatures from Longhi or Carpaccio, birds and snakes, eyes, leaves, parrots, astonishing

banquets and hunting parties, torn from their natural setting and placed in startlingly confusing landscapes. This is an "

Esmeraldized" world, writes the critic Vittorio Sgarbi. It appears unmistakably in pictures, bottles, table-mats, screens,

trays, cupboards, in her son's bathroom. Items in daily use and others, detached yet still useful. Behind them, hard work and great

patience, conscientious, clear-sighted craftsmanship. Esmeralda is proud of her artist-craftswoman role.

Her work is reminiscent

of the so-called Venetian arte povera, collage as a humble but rich art, and with illustrious predecessors. If its distant

ancestor was Arcimboldi the modern master is Fabrizio Clerici, and inspiration could come equally from Bosch and Surrealism.

Shy to the point of seeming to be distant, retiring, hesitant in talking about herself, quick to fall silent, perhaps too "different"

for a world intent on self-advertising, Esmeralda Ruspoli is the daughter of Marina Volpi and Carlo Maurizio, "Picci" Ruspoli,

Prince of Poggio Suasa, scion of an ancient and illustrious Roman family. She enjoyed a privileged childhood, spent between the

Palladian villa so beloved of her mother at Maser, the enormous, rather dark residence of her grandfather Giuseppe Volpi, Count

of Misurata, in Rome and the sunny Governor's residence in Tripoli, with its grapefruit and orange groves, the Arab garden, the

desert horsemen with their scimitars and rifles. But Esmeralda, like all children, was fascinated by scissors and pieces of paper

which fluttered to the ground as soon as they were cut. "I was a shy child: ' she remembers. "Adults seemed to me to be

aggressive beings and the other children just smaller-scale copies of the adults. So I found my happiness in solitude: in a corner

at Maser, staring at the palm fronds moving in the air, the birds in the sky; on the .patio where the bats had nested up between

the columns; on the terrace in Rome studying the bees among the roses; in the abbey at Farfa discovering what I could about the

life of a little field mouse. Perhaps the fairies would reveal enchanted castles in a drop of water, elves lead me to subterranean

kingdoms through a hole in the trunk of an ancient tree. I soon started to cut out pictures and put them together to fix my imaginings.

It all started like that: cutting out my dreams: ' And breathing the art of Paolo Veronese, Andrea Palladio, Piranesi, Carpaccio,

Longhi..

Then she met Giancarlo Sbragia at the Rome Academy of Dramatic Art, a young actor whom Silvio D'Amico suggested should

prepare her for an exam: then came marriage and three children, Mattia - an actor like his father - Viola and Ottavio, a musician.

Thus, with courageous indifference to the expectations of international nobility, she began her adventure in the theatre and the cinema

(from L'Avventura of Michelangelo Antonioni to Romeo and Juliet of Zeffirelli) and four years in repertory theatre with

the Teatro Stabile of Genoa, performing Goldoni in Venetian dialect from Moscow to Venice itself. At her heels, as always, her animals.

She smiles as the remembers her first train journey at the age of ten in a wagon-lit from Rome to Venice, with the inevitable governess

and a cage draped with a cloth: inside there were eighteen chicks, a hen and a cockerel. At dawn, the cock crowed. Still, wherever

she is, whether in New York or Maser, Panarea or Brazil, she is accompanied by Pacca, an easy-going pink Persian cat that was given

her by the family of Luchino Visconti, Ona and Oliver, her mild-mannered greyhounds, and Spezzatino, the inseparable, faithful and

now somewhat elderly mongrel.

Nowadays, after a pause, her collage work has taken commanding charge of her life again.

In 1957, Dino Buzzati, entranced by her "instinctive taste, whimsical imagination, her feel for paradox and the absurd, her

irreverence'; was highly amused by a leg created out of three overlapping nineteenth century women, six shinČbones, a parrot,

a pistol and a cardinal. But for Esmeralda, delighted enjoyment lies in the marvel of this precise and ordered chaos, where images

express themselves violently and at the same time belong to the gentle reality of a "mystery understood" which is continually

renewing itself and everything. Why not, she asks, a duck made of seaweed, a mountain of people, a bird of fish and

soldiers? By "cutting out dreams" simply and artlessly, Esmeralda reveals herself. And likewise, she tells of what it's like to

wait for dawn with a cactus flower. "At Panarea, I spent a whole night being born and dying with a cactus flower. When the cicadas

stopped chirping, in that moment of stillness which ushers in the night, the petals began to open. The crickets burst into their racket.

A faint perfume wafted by as the corolla unfolded to reveal a multitude of fine white filaments, like the feathery circlet crowning

the head of a crested crane, waving like the fronds of a sea anemone. The full moon, low on the horizon, red and enormous, slowly,

lazily rose into the sky and a blinding white light flooded the night. From nowhere, hundreds of transparent green insects appeared

and crowded into the vibrant heart of the flower, which seemed to enjoy their coming and going, welcome them into its now perfect

beauty with an intoxicating perfume. With the first light of dawn a bird sang and the flower died".

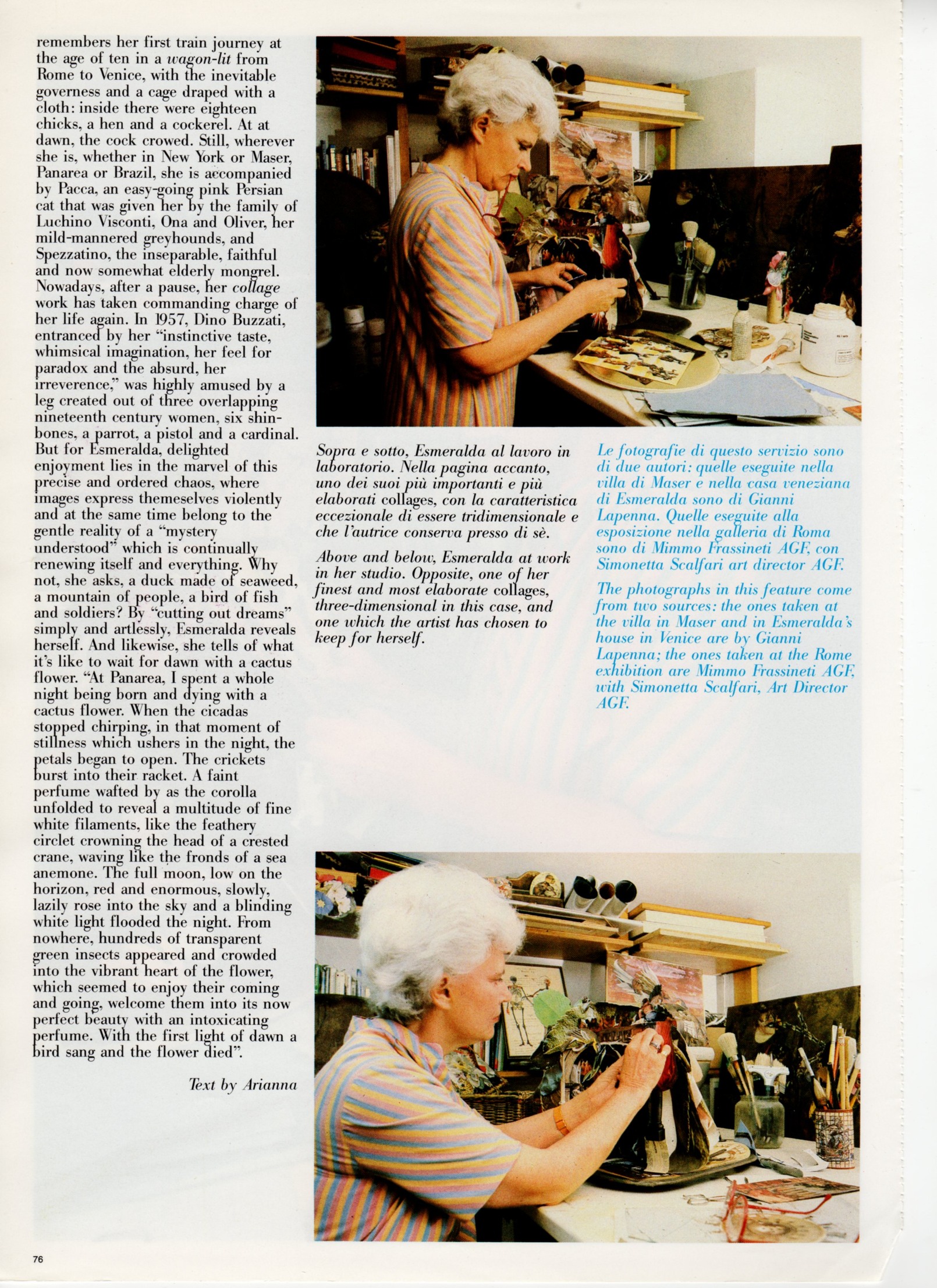

Captions

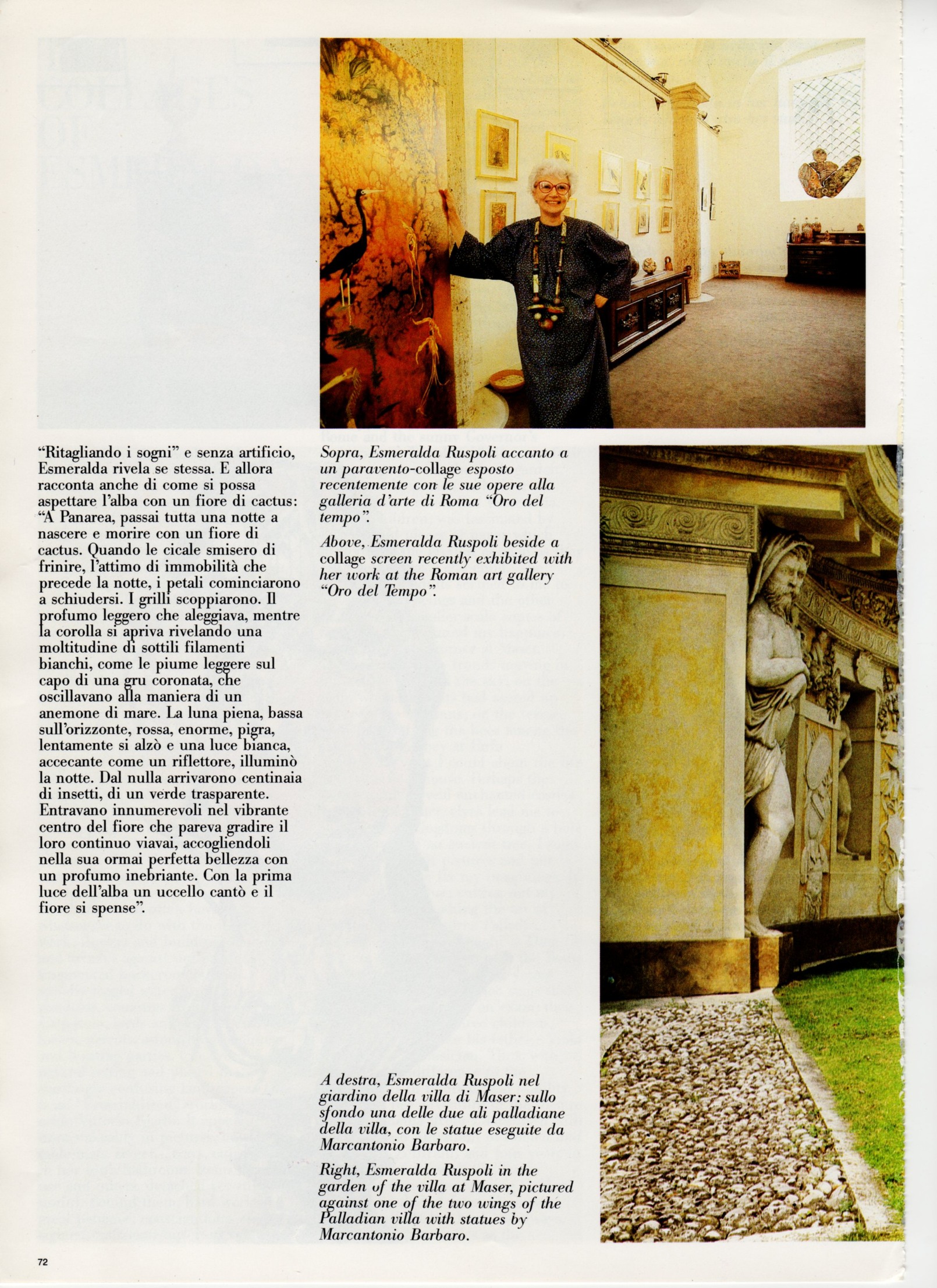

Below, Esmeralda in her house in Venice, which is also her studio

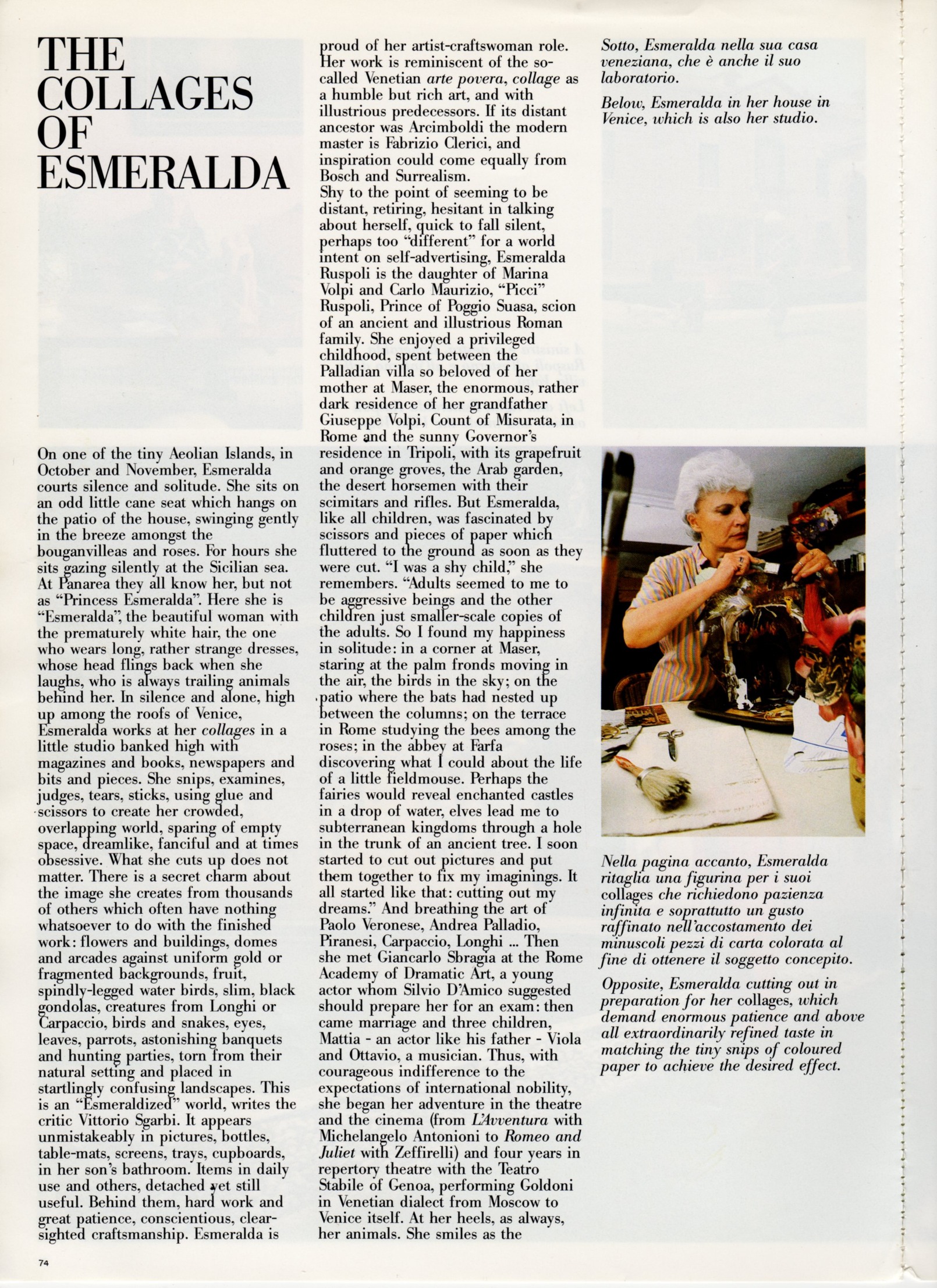

Opposite, Esmeralda cutting out in preparation for her collages, which demand enormous patience and above all extraordinarily refined

taste in matching the tiny snips of coloured paper to achieve the cleared effect

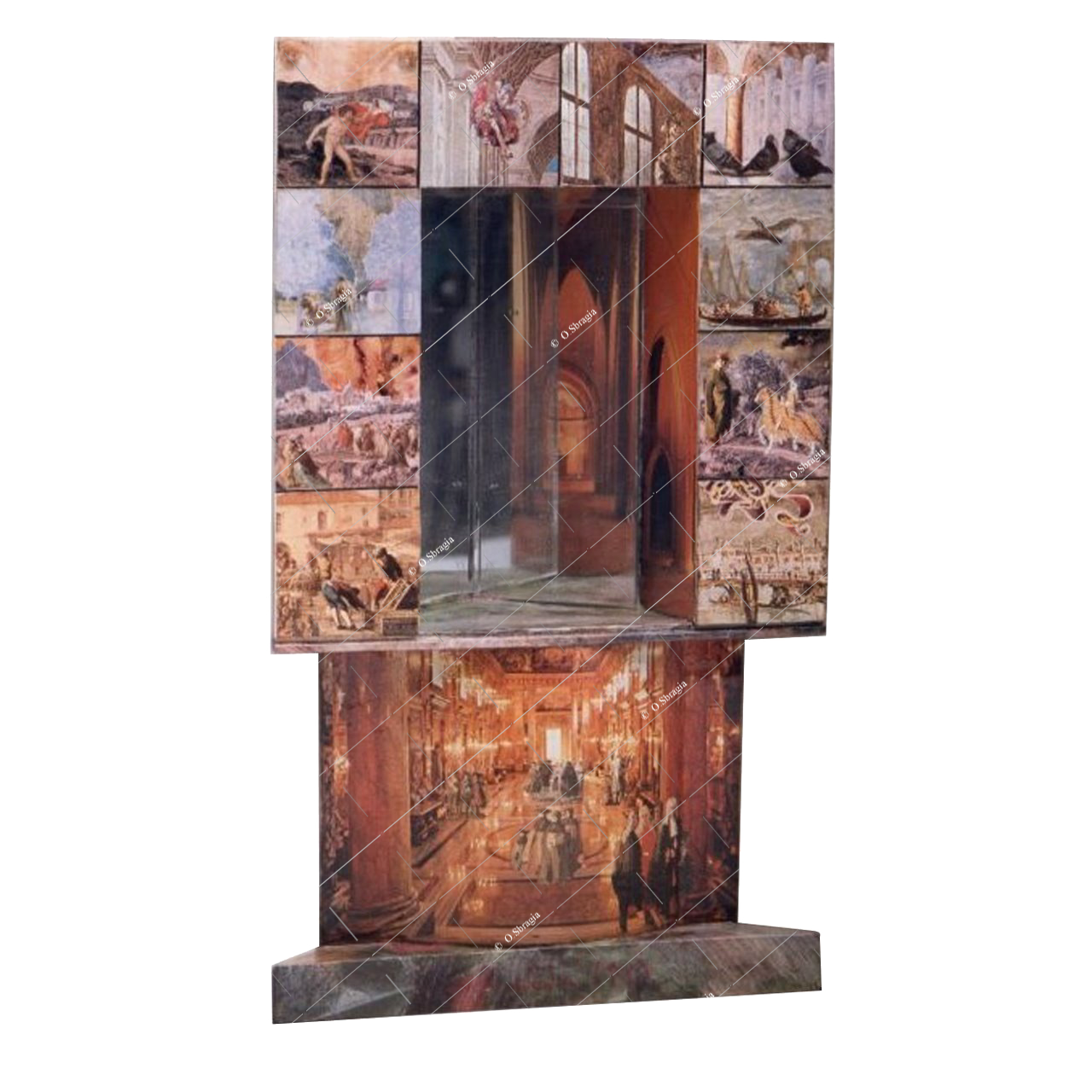

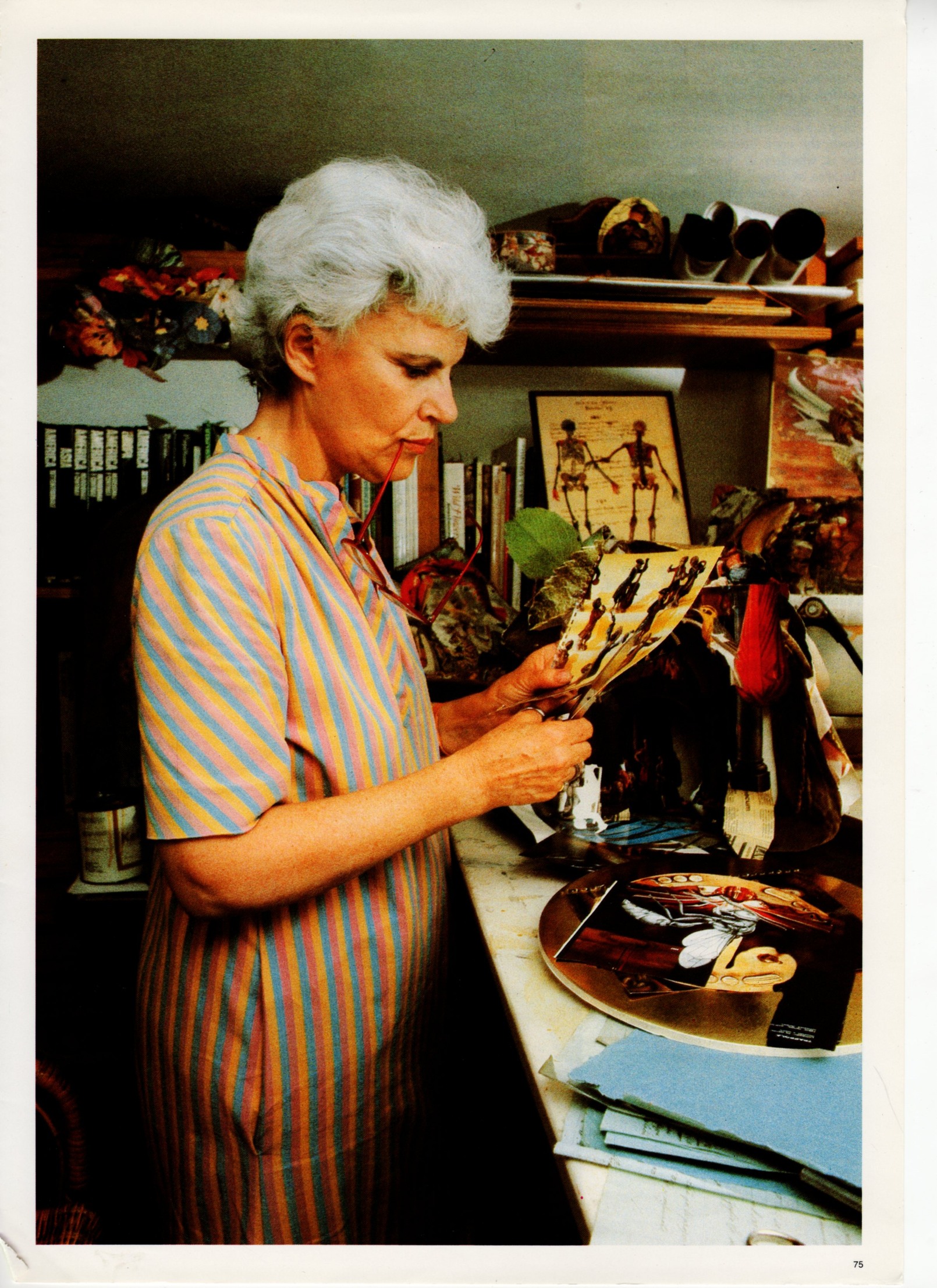

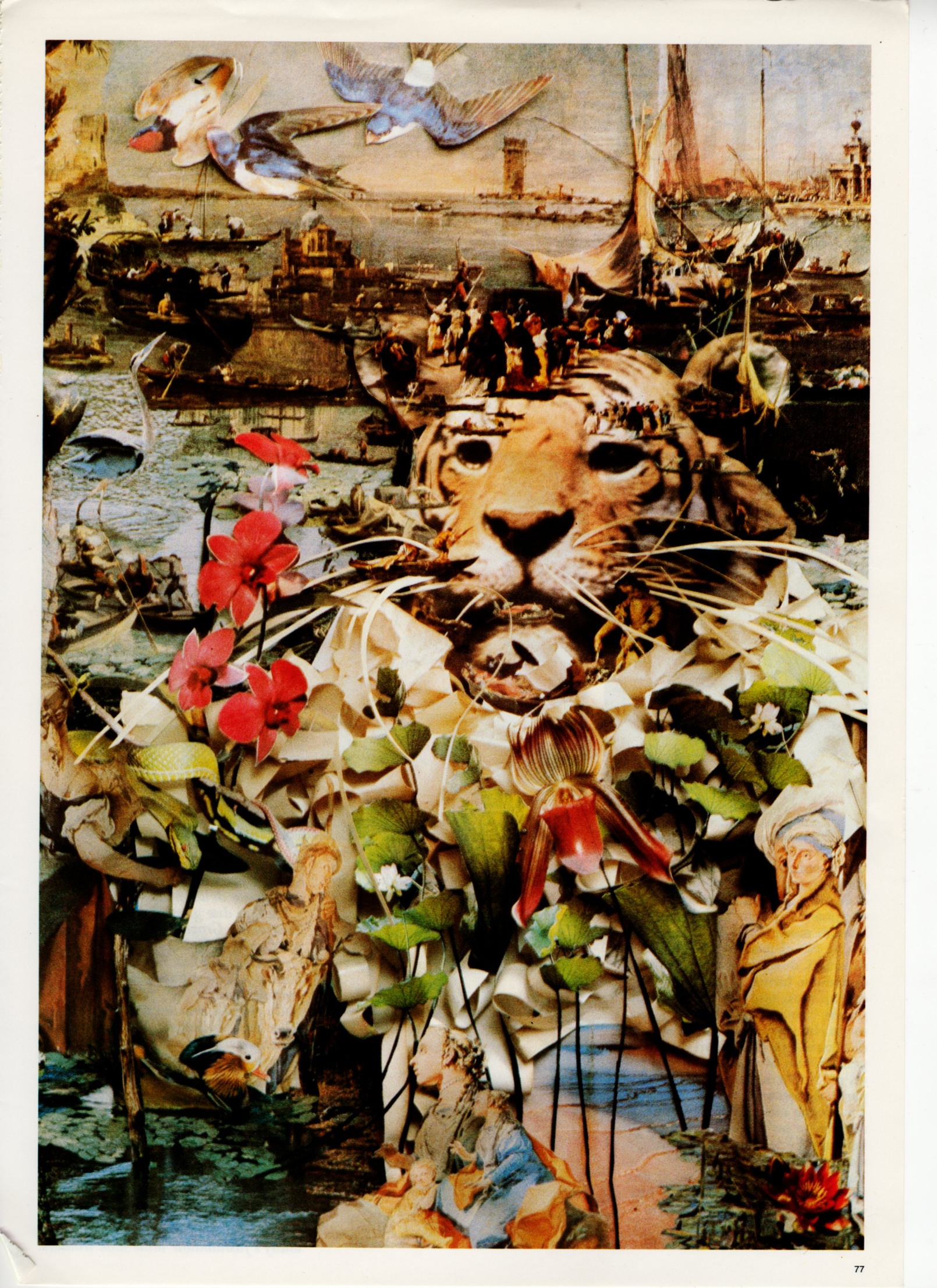

Above and below, Esmeralda at work in her studio. Opposite, one of her finest and most elaborate collages, three-dimensional in this

case, and one which the artist has chosen to keep for herself

[hide the article]

Esmeralda Ruspoli

Vogue DÚcoration, December 1986

Collages

[read the article]

[hide the article]

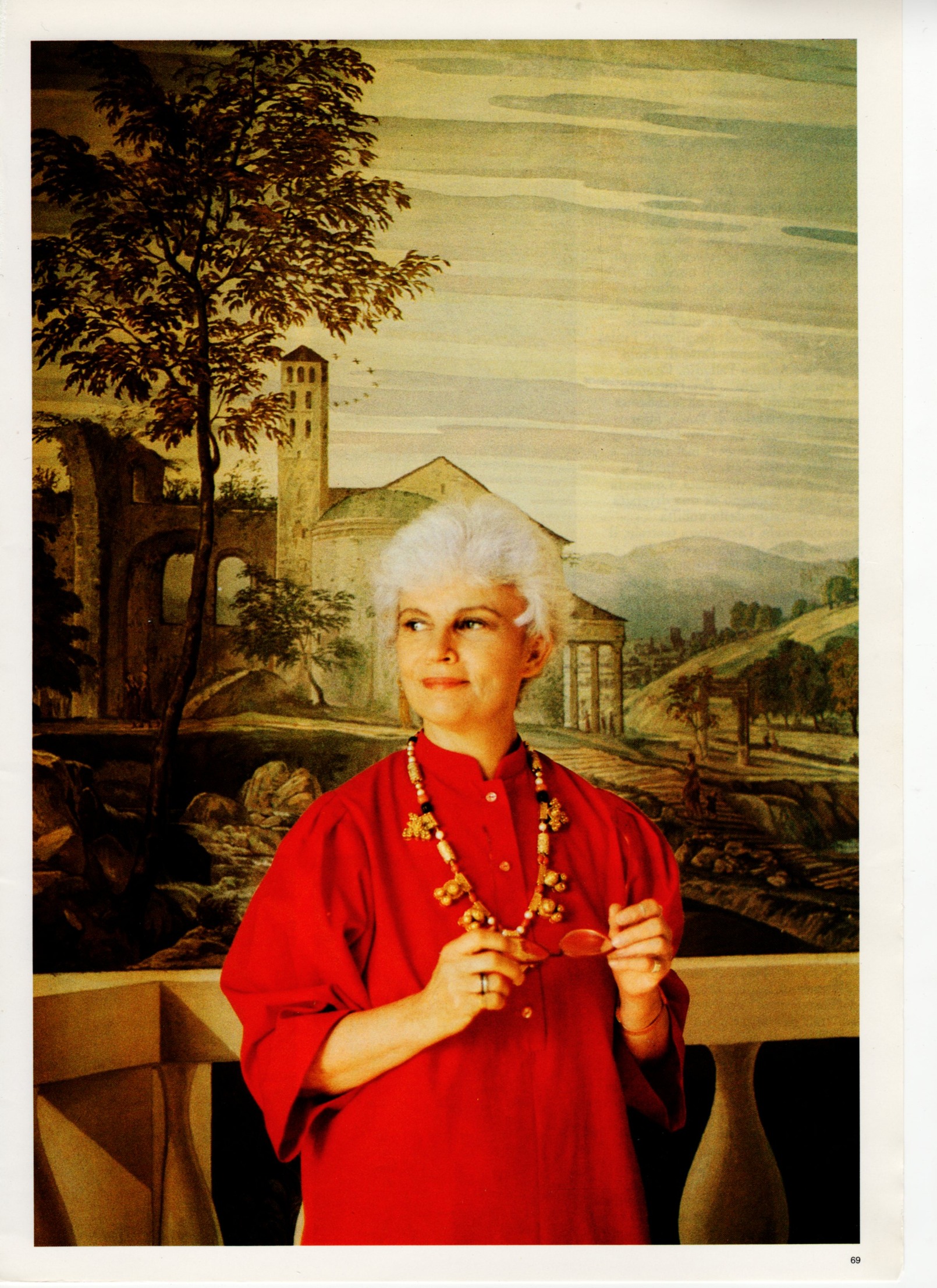

Her respectable silhouette and her head of silver hair are famous throughout Venice. A cosmopolitan aristocrat but a

twenty-year old in her soul, the Princess Ruspoli talks about her passion for collage which began in palaces, streets

and altanas and which owes so much to the Serenissima.

My name is Esmeralda Ruspoli. I was born in Rome on 24 June 1928 on the third floor of what once was Palazzo Volpi

on Via Quattro Fontane, at six o'clock in the morning, the daughter of Marina Volpi and Carlo Maurizio Ruspoli. Carlo Maurizio

in honour of Talleyrand, the famous ancestor of a paternal grandmother. My early childhood was spent with an English nurse,

servants, chauffeurs and automobiles in townhouses, country homes and villas in the desert like any other child belonging to

a privileged class of the world. Perhaps that was when my vocation for collage was born. When I was ill for a long time in

bed because of influenza or the measles, I remember that someone brought me some soft material made of flour and water. I don't

think that I thought I was making works of art then, but I can still feel the soft quality of that substance. That was also the

sensation of the feathers that my mother's maid used to fill the cushions, and in the kitchen, the rice that I took out of a box

and let run through my fingers! Touch. The apprenticeship of my hands evolved with a respectful lightness, almost a caress, letting

me discover objects simply by touching them. Animals, materials, hair, flower petals, skin, water. A dreamer since childhood,

images have always had a rather mysterious life in my soul and I encounter them in the faces of others. A person in a painting,

a tree in a photograph, an animal in an engraving, a landscape behind a painted Madonna, architecture, automobiles, colours: in

fact in everything that is printed on paper, I find fragments of a dream that belongs to me. I learned to look for them, to cut

them out, to assemble them and paste them onto a variety of supports. When I work, I use my hands for pasting, but also to make

the paste, and then I place the pieces of paper together in order to obtain a homogeneous result.

My life? Elementary school at the Villa Maser of Palladium where I lived with my mother, and the paper dolls' houses made in an

exercise book. Easter vacation at Tripoli in the enchanted garden of my maternal grandmother watching nature which told me marvellous

stories. The summer at Venice where in every corner of Palazzo San Benetto, I would encounter the fairies of my imagination in the

penumbra of the salons; and where my monkey played amid plants and climbed the courtyard walls, amusing itself by chasing the doves.

Later, secondary school at a lycÚe in Rome with rather insufficient results, and the view of great landscapes from high above the

rooftops of a friend's home, the Torre del Grillo. And then the war, adolescence, life that was beginning, imagination that blended

with reality. Love, children, the theatre, Panarea, the olive trees, friends, solitude, and always the collages, like an

inundation at times, which filling my life carried it toward others.

Captions

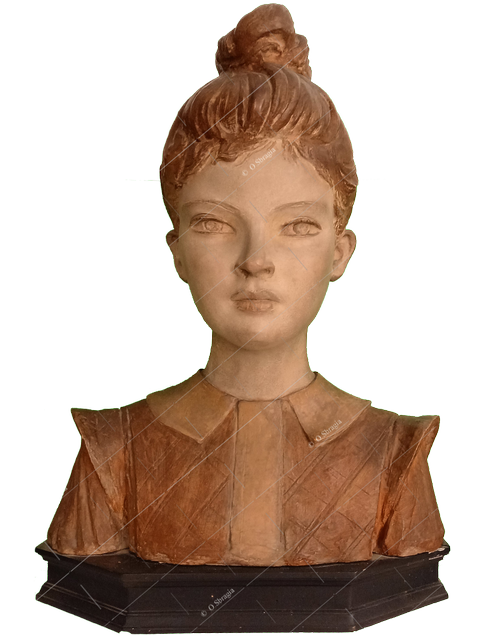

-A bust on its pedestal where dream and imagination blend

-Are these the balls dear to the Medicis that inspire Esmeralda Ruspoli?.

-Details of commode (below and facing page) inspired by the painted furniture of Ca' Rezzonico and Ca' d'Oro.

-Esmeralda Ruspoli photographed in front of the frescoes painted by Veronese in the Villa Maser where she grew up which belonged to her family.

- Right: a commode decorated with her collages.

- Below: amid precious books, a box: its interior is also treated with great refinement.

[hide the article]

Luciana Boccardi

Il Gazzettino di Venezia, June 1986

Art Collage Venice. The small pasted universe of Esmeralda Ruspoli

[read the article]

[hide the article]

Timid? I daresay this is not the first adjective that comes to mind for Esmeralda Ruspoli. The way she moves: her short

silent steps can be as deceptive as the flowing caftans she dons naturally as dressing gowns indoors and everywhere, which

make her seem more petite, or that crown of white hair framing her youthful face and worn 'with ostentation' almost always,

or even her restraint, a discretion to interpret as a need for abstractions, the pleasure of moving in the barely sensed worlds

of her curious collages. The show that recently closed which Ruspoli held of these 'objects' and 'works' at the La Soglia bookstore;

and the interest that it provoked is proof of the truth of an expression that began as an amusement, and - according to the words

of the author when asked too many questions - intends to remain an amusement.

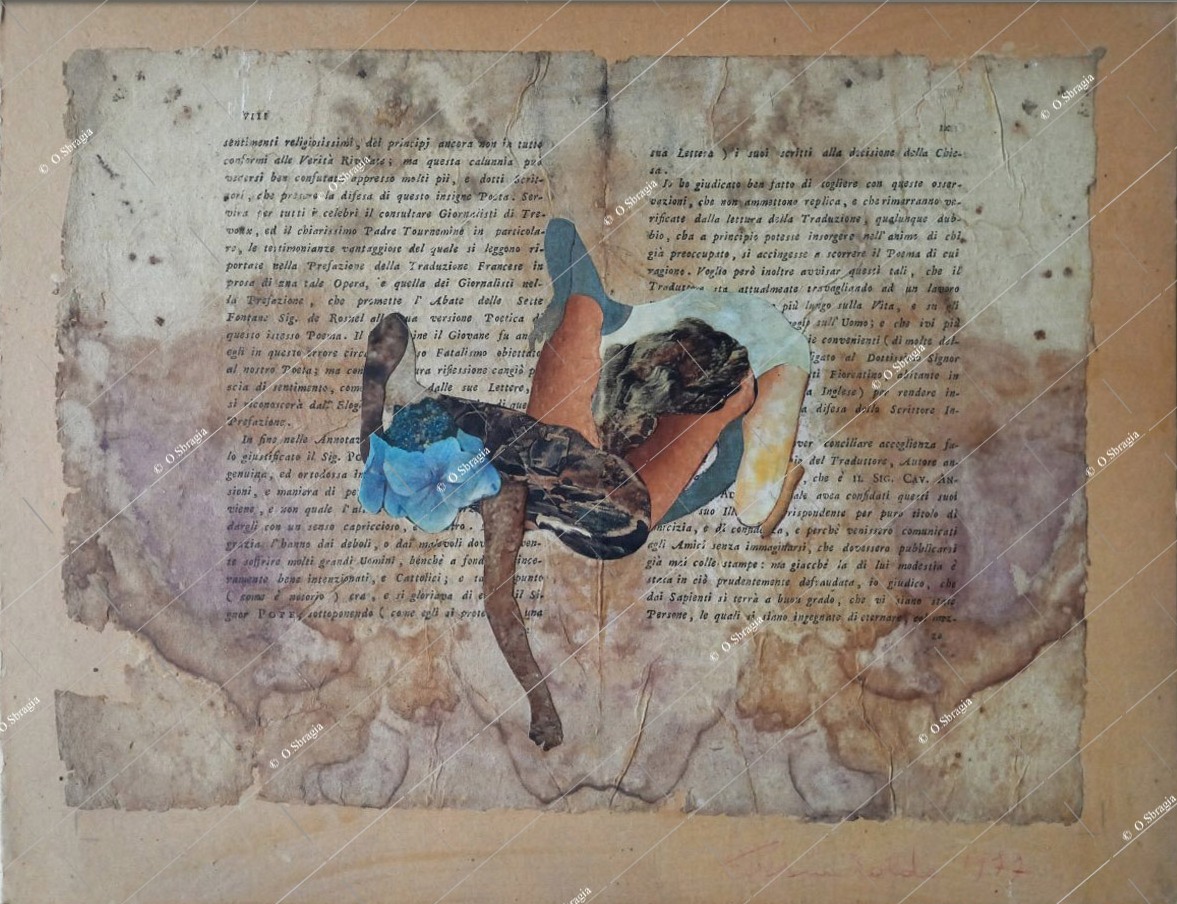

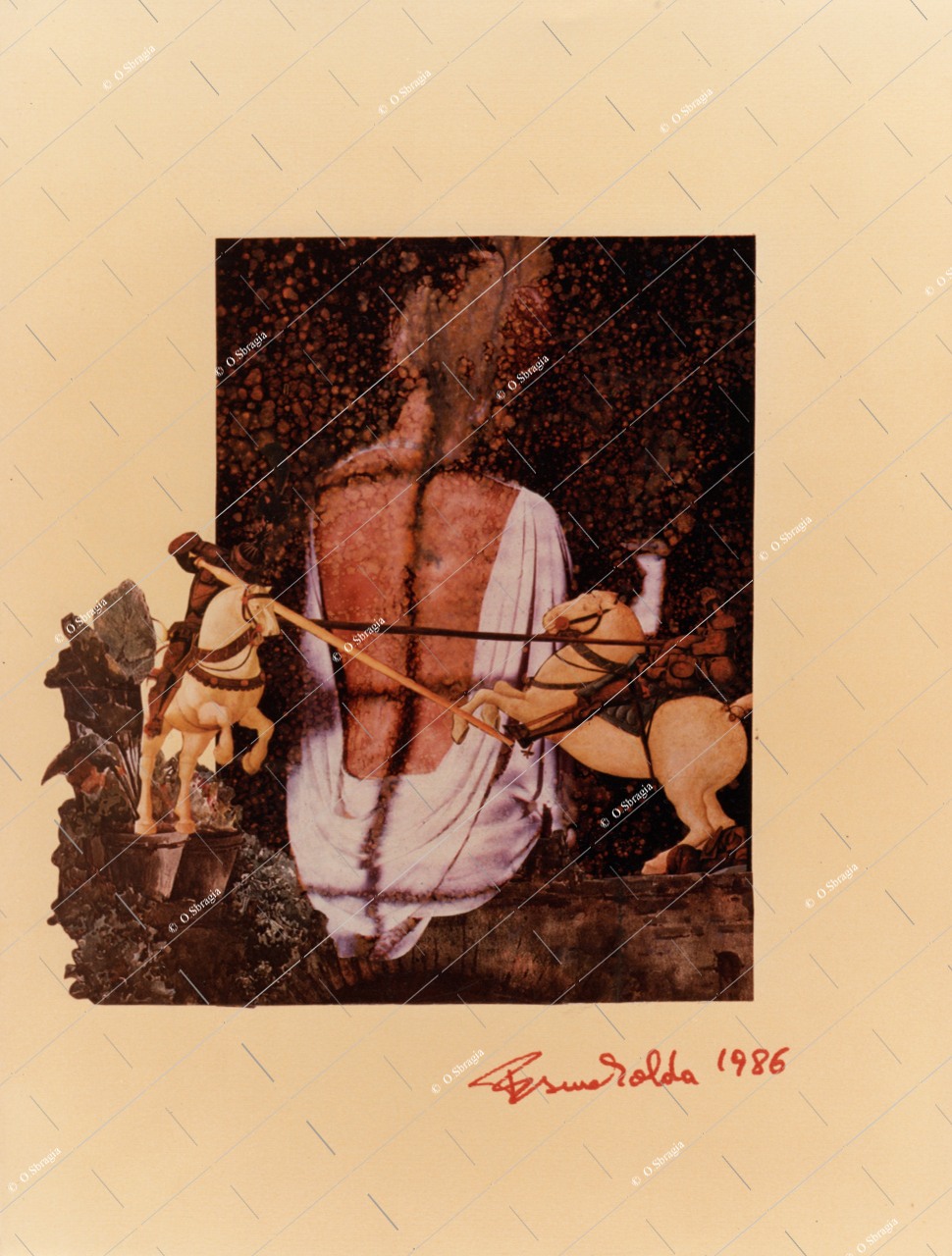

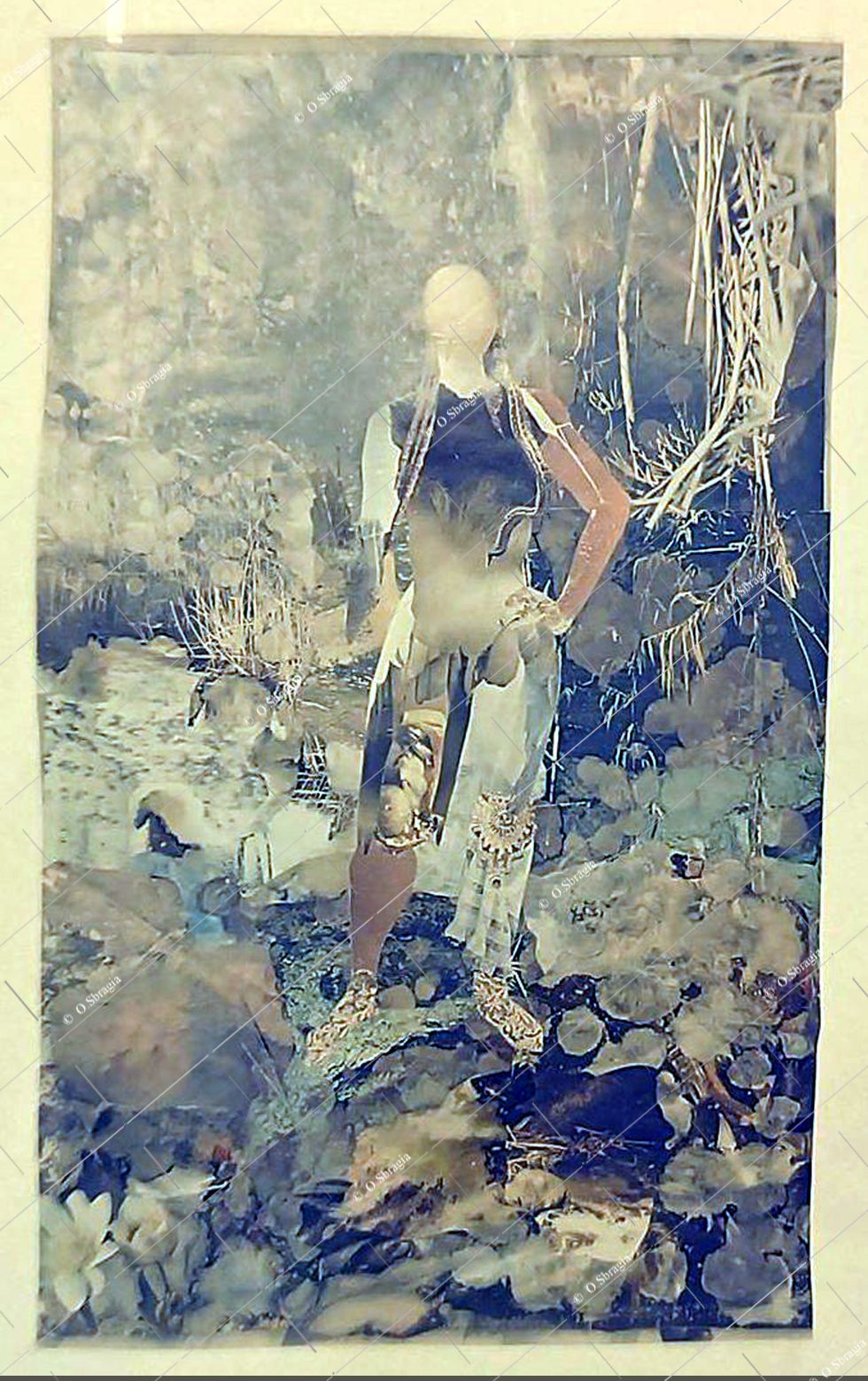

I try to analyse that 'pouf' dominating a full, long, eighteenth-century skirt made with a gigantic invented flower and those

draperies which in an alternation of shadows obtained with the lines of a newspaper accompany a mysterious female figure viewed

from the back. A landscape Ó la Watteau, pasted onto the suit of the cavalier next to her completes the message whose key might

be hidden in the esoteric. A small, candid witch? She might just be that, Esmeralda, taking delight in destruction, in that

repetitious gesture with scissors that cut up everything, destroy everything; always, ever since she was little, for the pleasure

of reconstructing everything differently, inventing everything with an indomitable despotic will.

Everyday objects: trays, boxes, an 'arte povera' chest that lived some century ago in some obscure Venetian kitchen, a

salon toy covered with different sized coloured pieces cut from newspapers, posters and magazines, each with its own obscure

significance; they emerge from reality to enter an irreverent, beautiful decorative make-believe protected by an impalpable,

transparent varnish. The metamorphosis, the mystery of the transformation, the intellectual adventure, the entrustment to the

already experienced, observed and read thereby recreating a timeless language with these, and to the fascination of a work that

began as an extravagant pastime for a young girl to whom nothing seemed to be denied.

Esmeralda as a child, in the luxurious

home of her mother, Marina Volpi at Villa Maser, or at the estates of her father, Prince Ruspoli, was at times a worrying presence:

her world was different, distant, lacking in any rules of time, and this may have been the spring that projected her into the temple

of make-believe: the theatre. Experience in the cinema, in the theatre, a marriage with Giancarlo Sbragia, three children. But those

pieces of coloured paper, written, drawn, which when she was little, she loved to paste - even in the important Villa Maser on the

door of her room (where they still are) were waiting for Esmeralda.

Today, and during the long months at Panarea, or in her home in Venice, at the Frari, the conversation about what has been has

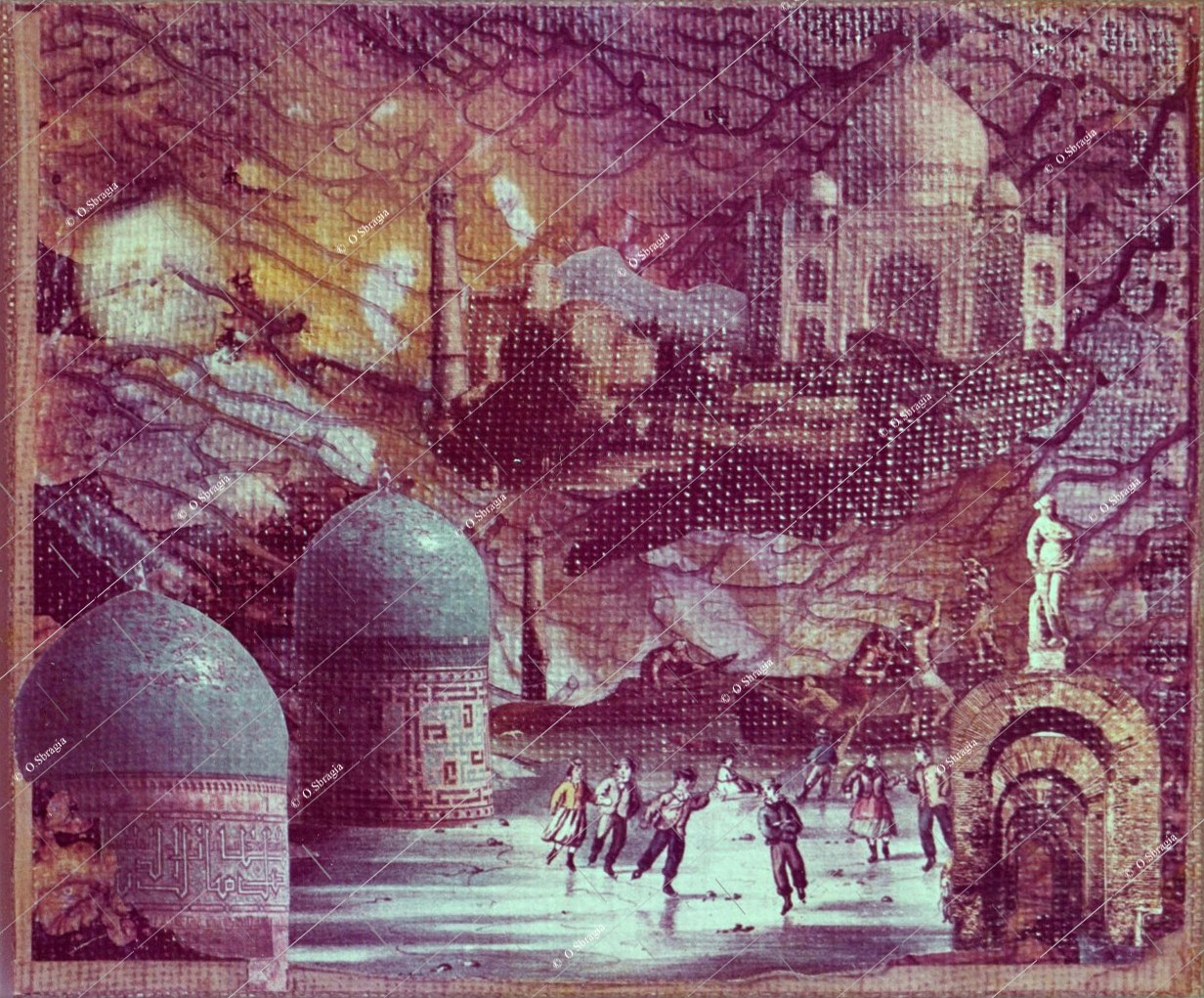

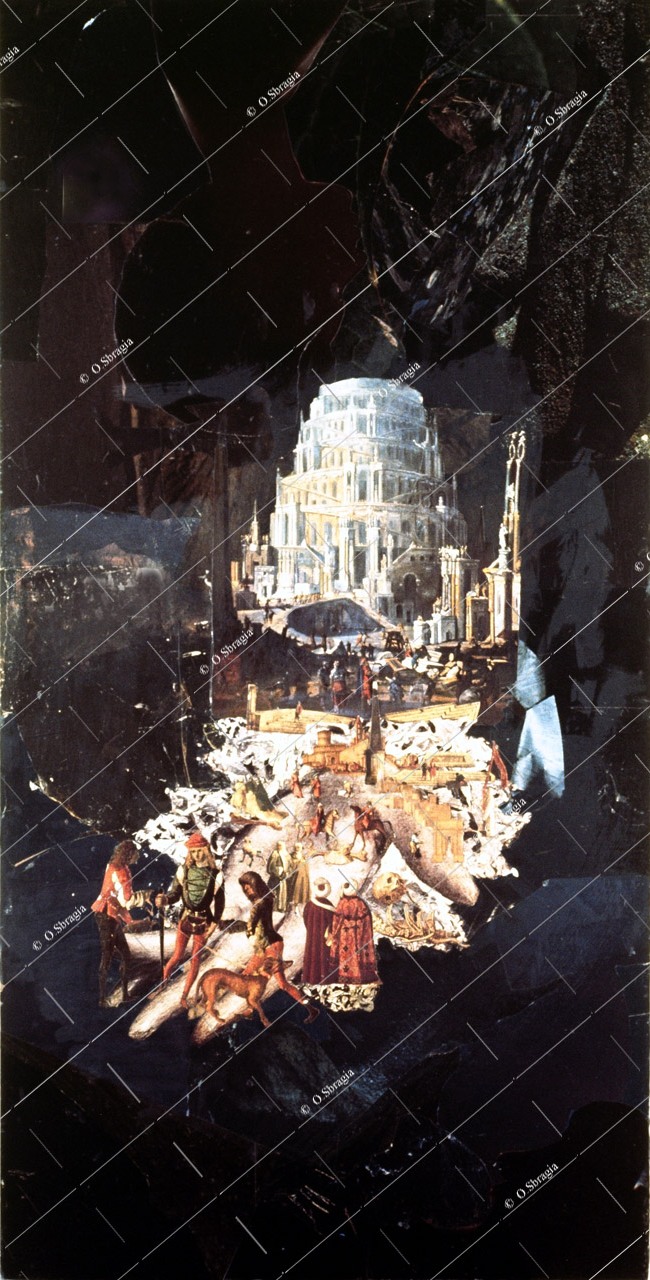

taken on a higher quality. Proof lies in her most recent works on gold backgrounds, immersed in the world of Carpaccio or improbable

scenes of a Middle Ages imbued with alchemy; a dictionary of the impossible suggested perhaps by the ghosts populating her feigned

solitude. Ruspoli pastes our universe with a taste of irony, joy, wickedness, aesthetic needs, or just for the fun of it.

[hide the article]

Patrizia Piccioli

Casa Viva - Scenografie di interni, 1990 (posthumous)

The Lady of Collages

[read the article]

[hide the article]

Princess Esmeralda Ruspoli, a prominent figure of Roman and Venetian high society, has for years developed and elaborated

the technique of collage which has become a veritable art in her hands. Many of her works are in the Venetian home we are

presenting where they have created an interior scenography that in no way detracts from the exterior one of the Serenissima.

Esmeralda Ruspoli, a Roman princess with Venetian roots, an actress in the heyday of Italian cinema (she had a leading role

in L'avventura of Antonioni), is an artist of extraordinary sensibility who has dedicated a great part of her life to

collages revealing a great capacity to note, understand and compress everything surrounding us. It would be opportune if, on

the next spatial spacecraft, hopefully in collaboration with all the governments of the planet, a collage were placed. It would

be a unique document for us to communicate our terrestrial reality with eventual aliens. In fact, although it might prove useless

for 'others', it would serve for the rest of 'us' to know and appreciate her art.

Art proposed by the object must be useless: only the impossibility of speculation allows whoever contemplates it infinite enrichment.

It is, however, indispensible to understand the artist's intentions in order to understand it. Esmeralda has created a visual

encyclopaedia in which every image allows for a reading in a historical, scientific and aesthetic key of what it was and how it

was until now.

Everyone of her works, be they a polyhedron, a sphere, a plate, an ambience, or a canvas, is re-clothed and inhabited by documents

of reality, cuttings from the most varied matrices: pictures, prints, fabrics, drawings, photographs, etchings both side by side or

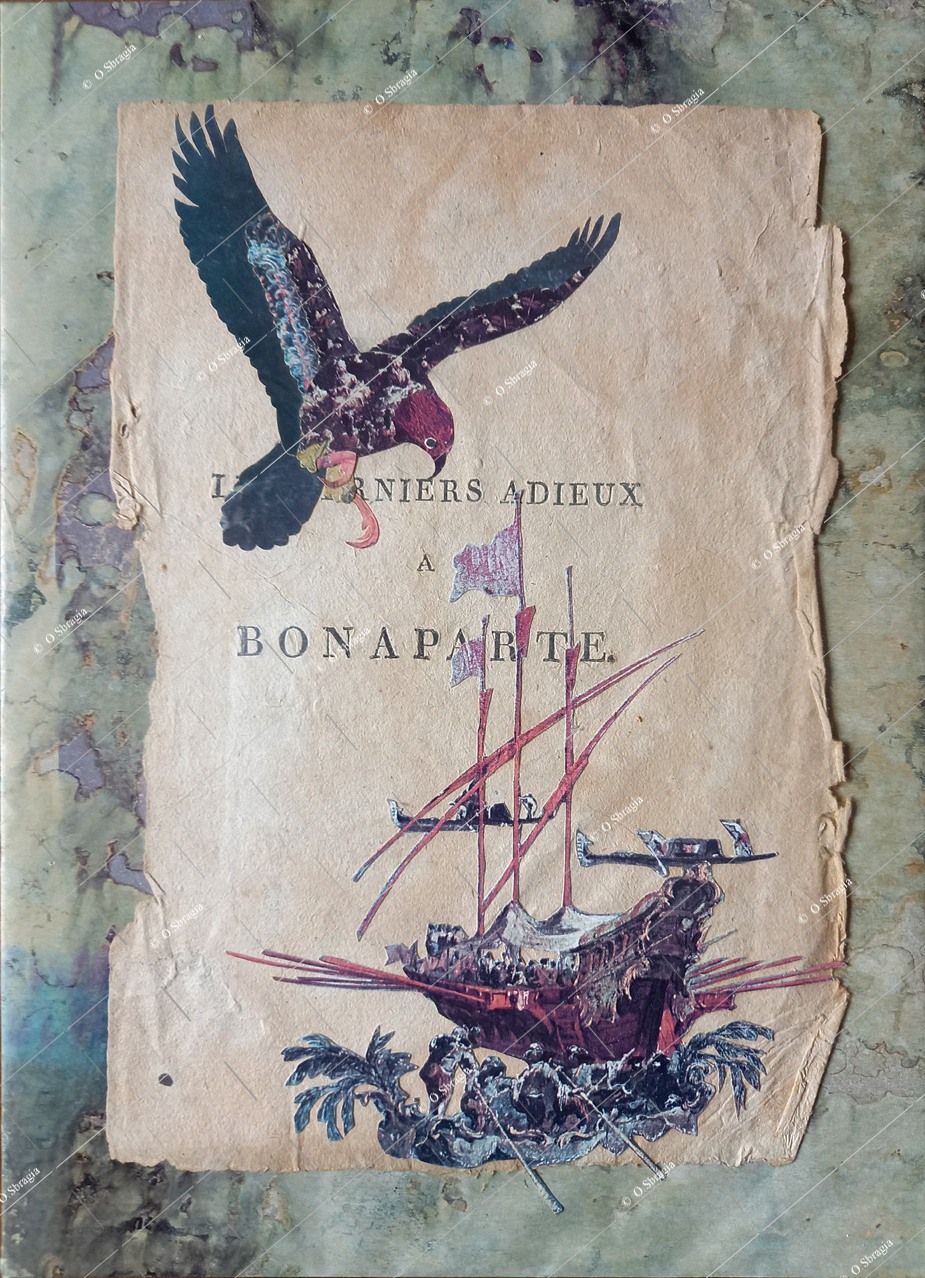

overlapping without any temporal or apparently historical ties. Thus it comes as no surprise to see the image of a Flemish watchmaker

finding shelter in Hadrian's Villa or Paolo Uccello's grooms present at the coronation of Napoleon Bonaparte, while peripatetic

philosophers watch in astonishment a show of la Goulue at the 'Chat Noir'. A kind of representation of the infinite combinations

of reality where time and physical space annul one another with the extraordinary faculty of blending everything into one thought,

and underlining the artist's intention of presenting with extreme order, pietas and happiness all that has been in human history

and in us as we are now.

Many of the works of Esmeralda Ruspoli are present in the home of a young musician -and illustrated in these pages -who lives in a

simply structured and functional apartment in a Venetian palace. Since whoever wishes to have a home in Venice has to accept the fact

that the interior dÚcor will inevitably be compared to that of the exterior: the proprietor here has opted to adapt many artworks to

the space necessary for daily living, privileging the surprising collage objects of Esmeralda there by permitting the dwelling to live

harmoniously with the city and contribute to enriching it with images and an atmosphere so there is no noticeable environmental gap for

those who enter or exit his home.

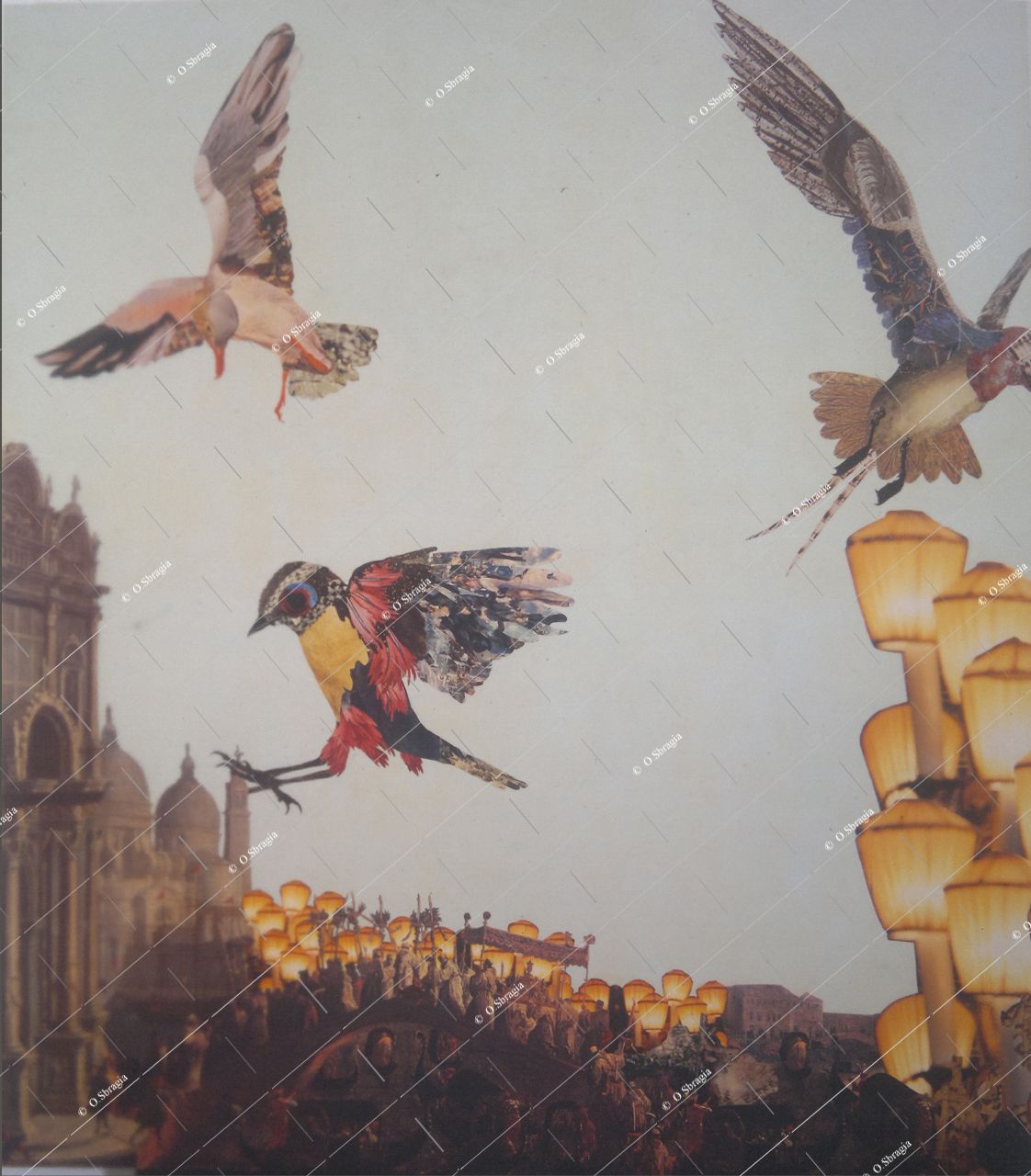

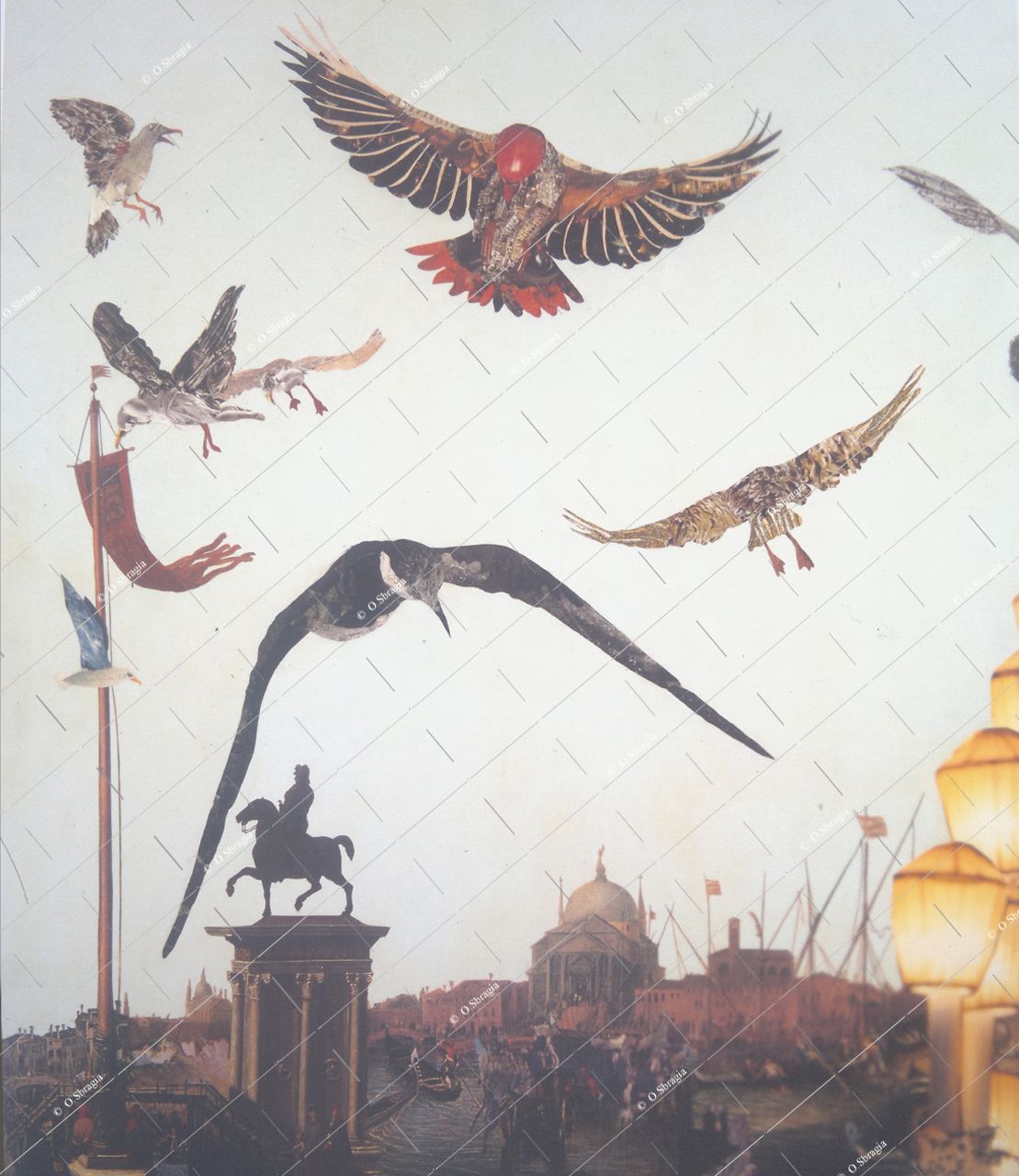

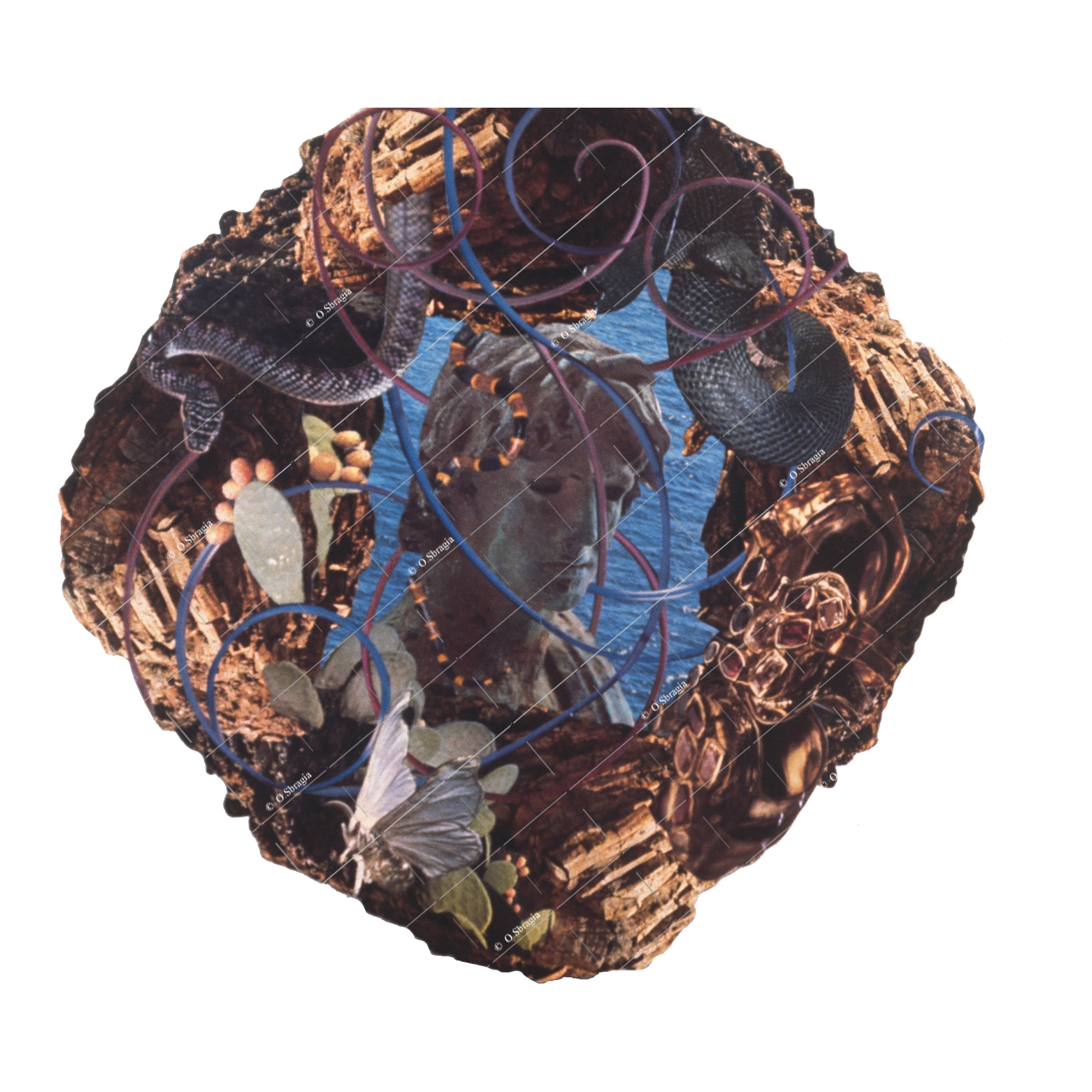

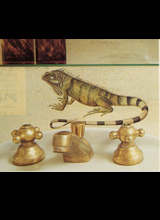

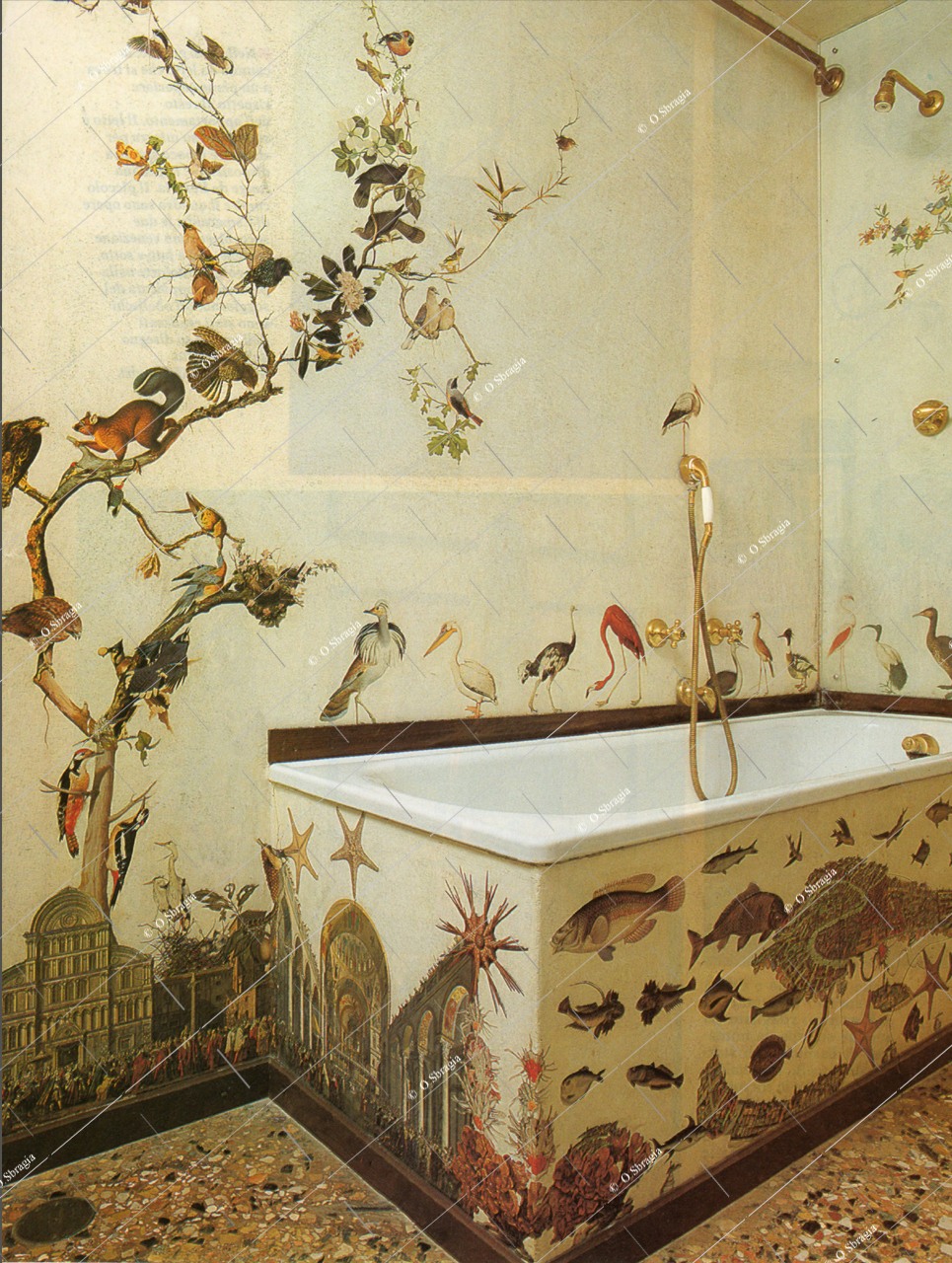

The striking bathroom is in itself a work of art, a kind of ancient'salon of waters' - the same water surrounding the campiello

in support and defence of Venice - where entering from the outside and cut out from ancient prints, these images of basilicas, flocks

of birds - both migratory and non-migratory, in the air and on the ground, and fruits and flowers create a light, ethereal atmosphere

like the fluttering of butterflies attracted by the light of a ceiling chandelier.

Photo captions:

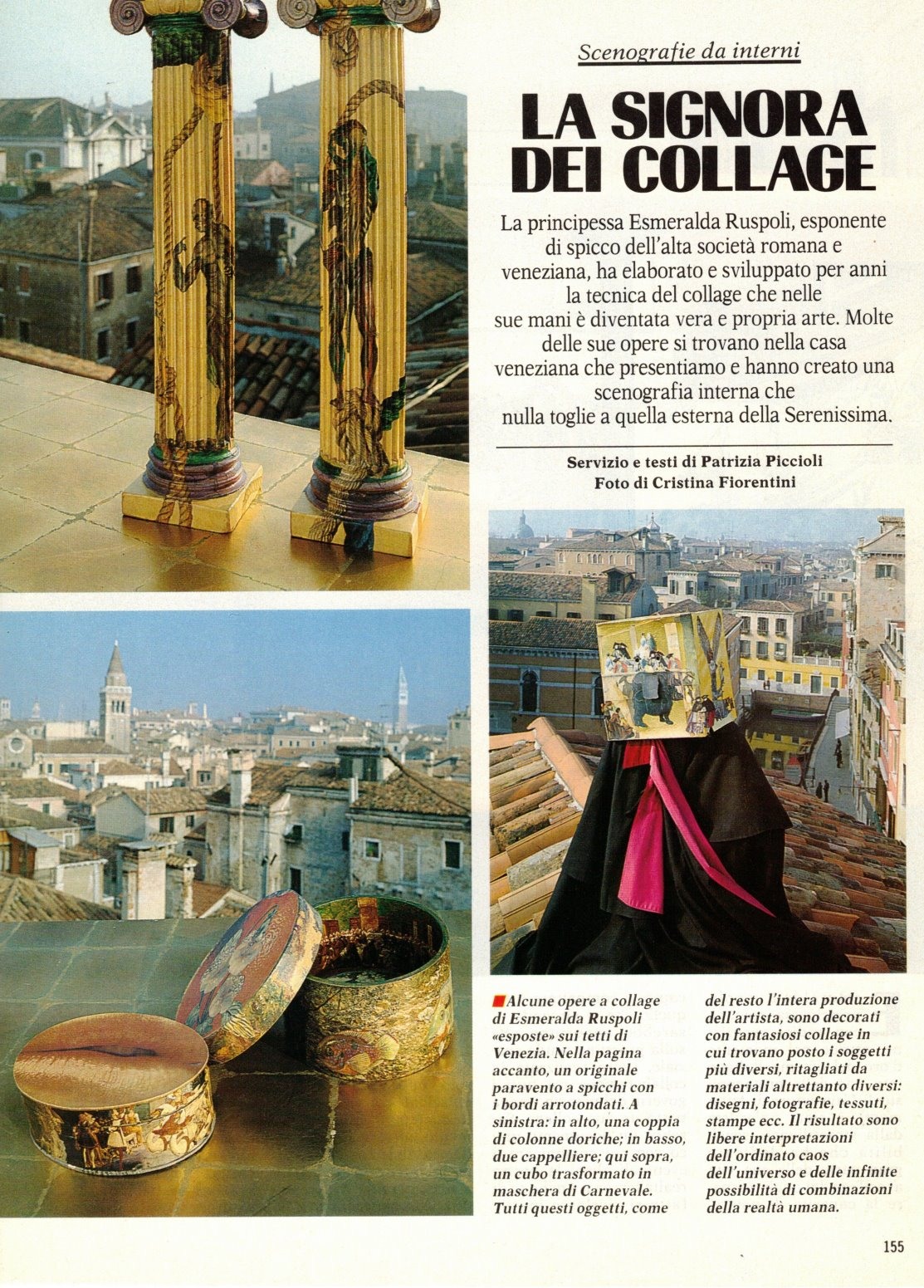

Some collage works of Esmeralda Ruspoli źdisplayed╗ on the roofs of Venice.

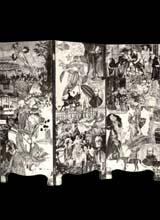

Facing page: an original panelled screen with rounded edges. .

Above left: a pair of Doric columns; Below: two hat-boxes; here above: a cube transformed into a Carnival mask.

All of these objects, like the rest of the artist's entire production, are decorated with imaginative collages in which the most diverse

subjects are cut out from equally diverse materials: drawings, photographs, fabrics, prints, etc. The results are free interpretations

of the ordinary chaos of the universe and of the infinite possibilities of combinations of human reality.

Left: a glimpse of the sitting room, characterised by a precious plan of the Serenissima of 1729. Sofas and armchairs were covered with

Indian material by an up holster. On the library, spheres and wooden boxes decorated with collages by Esmeralda Ruspoli. Close-up: ladder

to the loft where a 1940s pantograph lamp hangs. In the other two photos: loft covering part of the sitting room; the structure, made of

scaffolding tubes and wooden beams, serves as a study-guest room. The bed, in light German wood of the early 20th century, is covered with

the same material as the armchair. The table is in Empire style.

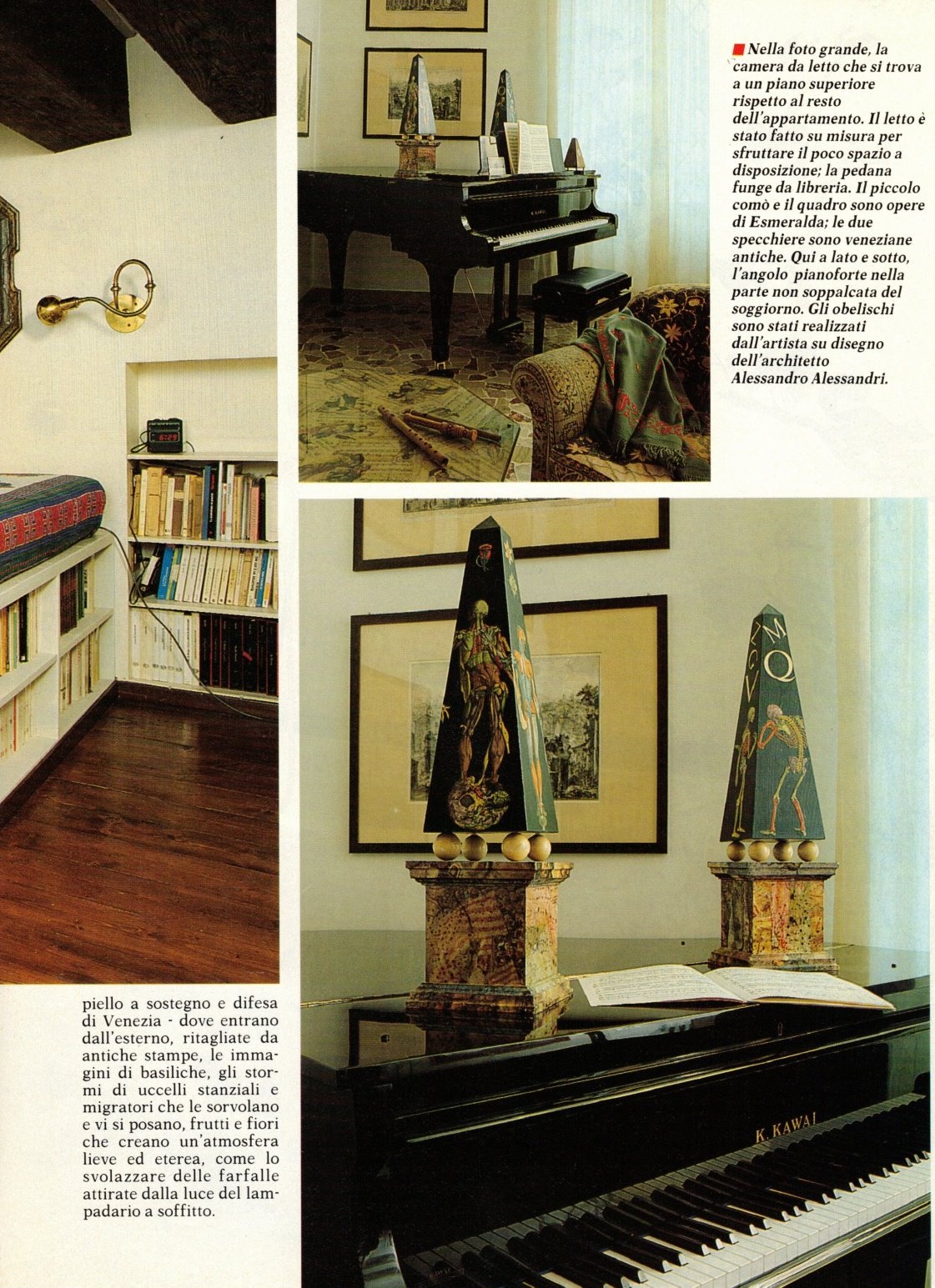

In the large photo: the bedroom on the floor above the apartment.

The bed was built to exploit the small space available; the footboard functions as a bookcase. The small chest and the picture are works

of Esmeralda; the two mirrors are Venetian antiques. Here to one side and below: piano in the sitting room area not covered by the loft.

The obelisks made by the artist on a design by the architect Alessandro Alessandri.

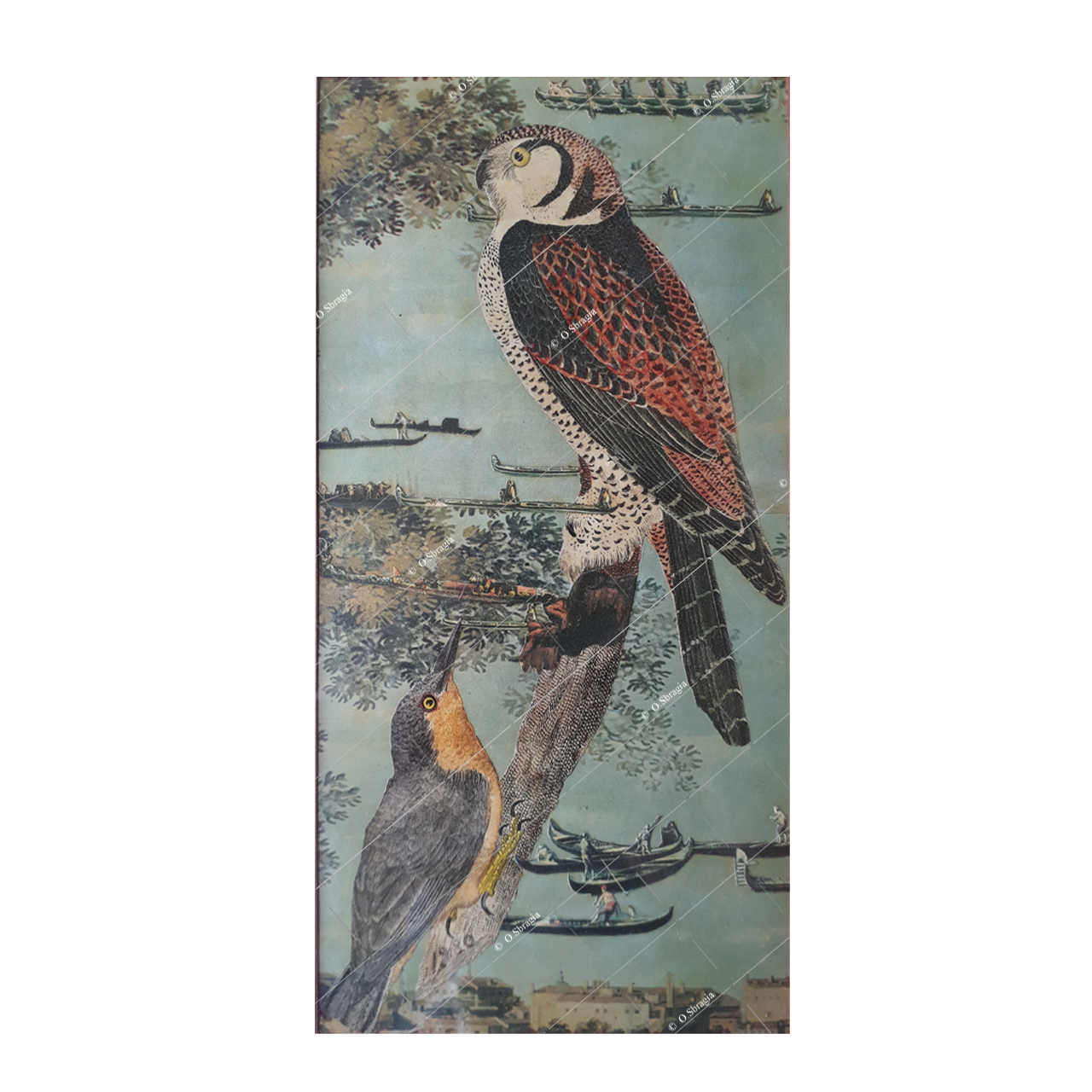

On these pages: the master bathroom, the most extraordinary room of the entire apartment that the art of Esmeralda Ruspoli transformed into

a modern version of the ancient 'room of waters'. Along the base of the walls runs a row of the most beautiful monuments of Venice from which

'branch out' a whole plant and animal world: trunks, leaves, flowers, but also butterflies, squirrels, cranes, storks, flamingos, woodpeckers,

ostriches and many others. The external covering of the tub has instead become the perfect place for an imaginary aquarium populated by exotic

fish and starfish. Lastly, a flight of birds crowns the ceiling light. On the right: detail of basin where a sympathetic yet innocuous chameleon

observes ablutions. Below right: another detail of the bathroom: a group of birds of prey - one of which is sitting on the dome - in flight around

the Church of San Giorgio. The floor is in marble granulate. The small black shelved chest is an old Chinese piece.

[hide the article]

Interview one

Interview one

Paolo Cavallina

OGGI, November 1966

La Nipotina di Gengis Kahn

[read interview 1 ]

[hide interview 1]

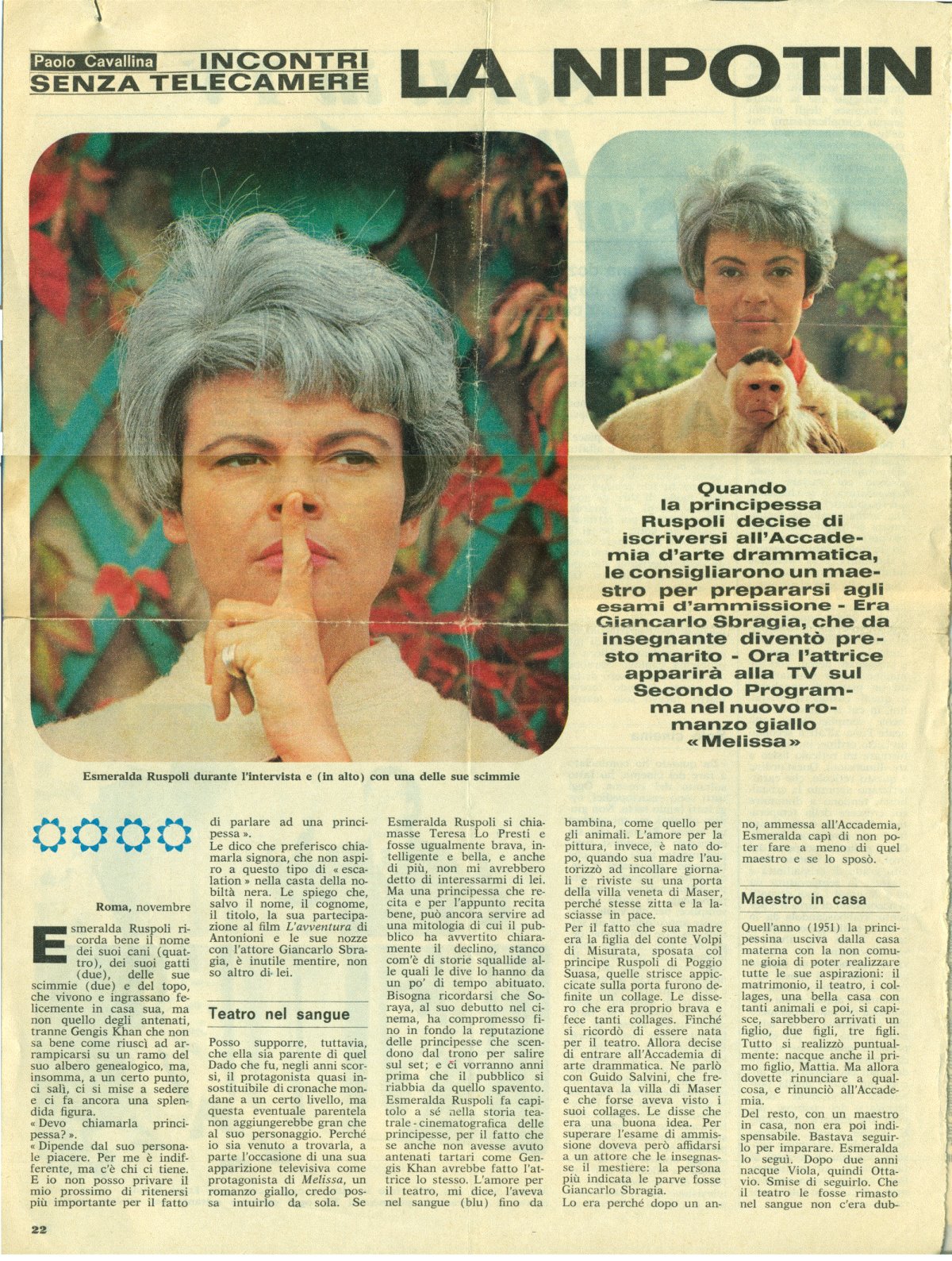

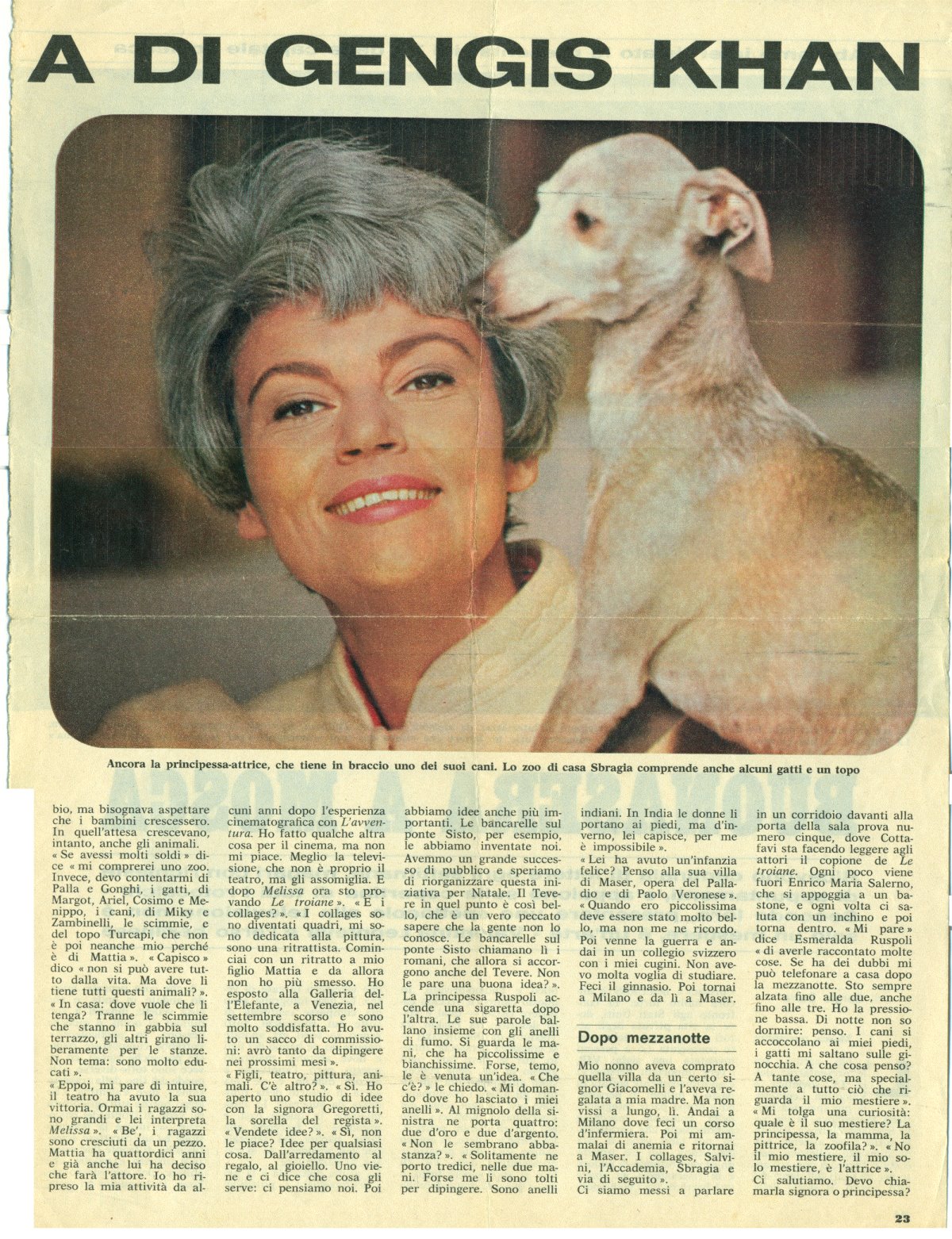

When the Princess Ruspoli decided to enrol in the Academy of Dramatic Art, a teacher was recommended to prepare her for the admission

exams; it was Giancarlo Sbragia, who from teacher soon became her husband. Now the actress will appear on the Second Programme of the TV

in the new mystery "Melissa".

Esmeralda Ruspoli remembers the names of her dogs (four), cats (two), monkeys (two) and mouse, who live very well in her home, but not

those of her ancestors, except Genghis Khan: she is not quite sure how he managed to climb onto a branch of her genealogical tree, but at

a certain point, he did and he still sits there as a splendid figure.

"Should I address you as princess?"

"Depends on you. I am indifferent, but for some it's important. And I am not about to make anyone feel less important just because he

is talking to a princess."

I say that I'd prefer to call her signora, and that I do not aspire to this kind of escalation in the caste of the black nobility. I explain

that except for her name, surname, title, part in the Antonioni's film "L'avventura" and her marriage to the actor Giancarlo Sbragia,

I really know nothing else about her.

Theatre in the blood

I suppose, however, that she is a relative of that Dado who was recently almost the only protagonist of certain local gossip sheets, however,

this possible relationship adds nothing to her figure. Why I have come to see her, apart from her television appearance as the lead in the mystery

Melissa, I am sure she knows. Were Esmeralda Ruspoli named Teresa Lo Presti and were equally good, intelligent and beautiful, I would not have

been told to interview her. But a princess who acts and, for that matter, acts well, can also serve a mythology that the public has clearly noticed

to be declining, tired as it is of the squalid stories that the stars have been filling the press with for some time. One need only recall Soraya